Why Prize Money Fuels F1's Competitive Divide

How F1's prize distribution and legacy bonuses widen the financial gap, entrenching top teams and limiting smaller teams' ability to compete.

Formula One’s prize money system creates a massive gap between top and lower-tier teams, directly impacting competitiveness. In 2024, F1 distributed $1.266 billion in prize money, but it wasn’t shared equally. Historical bonuses and past success play a huge role in determining payouts, favoring teams like Ferrari and Mercedes while leaving smaller teams struggling to compete. For example:

- Ferrari received $63.3 million in historical bonuses alone, regardless of performance.

- Mercedes earned $101.28 million from a "previous success bonus", while Williams earned just $4.22 million.

- Performance payments for the 2024 season ranged from $132.9 million for McLaren (1st place) to $57.9 million for Sauber (10th place).

This creates a cycle where wealthier teams invest more in R&D, facilities, and top drivers, further widening the gap. Smaller teams, earning as little as $60 million annually, face limited resources and struggle to close the performance deficit.

Key Issues:

- Historical bonuses (like Ferrari’s) guarantee income for legacy teams, regardless of results.

- A decade-long success bonus rewards past dominance, leaving newer or less successful teams behind.

- The lack of transparency in prize distribution makes reform difficult.

Proposed Solutions:

- Phase out legacy bonuses like Ferrari’s over time.

- Shorten the "previous success" bonus window to five years and reduce its share of the prize pool.

- Introduce a minimum prize payout (e.g., $90–100 million) to help smaller teams compete.

- Create improvement bonuses to reward teams climbing the standings year-over-year.

These changes could reduce the financial gap between teams and create a more competitive F1 grid, but resistance from top teams and the Concorde Agreement’s terms make reform challenging.

How Many MILLIONS Do Formula 1 Teams Receive?

How Formula One's Prize Money System Works

Formula One distributes its prize money through three confidential channels outlined in the Concorde Agreement. While the exact figures remain undisclosed, estimates provide a glimpse into how some teams start each season with a considerable financial edge.

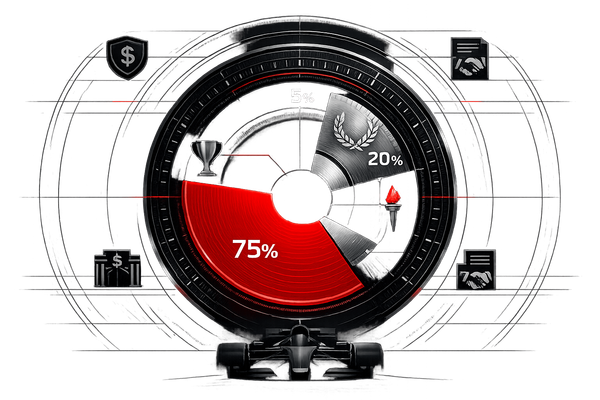

Prize Money Allocation Breakdown

The projected prize pool for 2025 is approximately $1.266 billion, divided into three main components:

- Ferrari’s Historical Legacy Bonus: Ferrari receives about 5% of the total prize pool - an estimated $63.3 million. This fixed payment acknowledges the team’s long-standing impact and global appeal, regardless of their on-track performance.

-

Previous Success Bonus: Around 20% of the prize pool (roughly $253.2 million) is distributed based on a decade-long points system for top-three finishes (2015–2024). Teams earn points as follows: one for third place, two for second, and three for first. Here's how the bonus is estimated to break down:

- Mercedes: 24 points ($101.28 million)

- Red Bull: 16 points ($67.52 million)

- Ferrari: 15 points ($63.30 million)

- McLaren: 4 points ($16.88 million)

- Williams: 1 point ($4.22 million)

- Performance-Based Payments: The remaining 75% of the prize pool - about $949.5 million - is allocated based on the 2024 constructors' championship standings. Each team’s share is determined by their finishing position, with an incremental difference of around 0.9% between placements. The estimated payouts for 2025 are:

| Finishing Position | Team (2024) | Performance Payment |

|---|---|---|

| 1st | McLaren | $132.9 million |

| 2nd | Ferrari | $124.4 million |

| 3rd | Mercedes | $115.8 million |

| 4th | Red Bull | $107.3 million |

| 5th | Aston Martin | $98.8 million |

| 6th | Alpine | $90.2 million |

| 7th | Haas | $82.6 million |

| 8th | Racing Bulls | $74.1 million |

| 9th | Williams | $65.5 million |

| 10th | Sauber | $57.9 million |

The gap in performance payments alone is striking - teams at the top earn $75 million more than those at the bottom. When combined with the other bonuses, the disparity grows even larger. For example, Mercedes, finishing third in 2024, would receive $115.8 million in performance payments and $101.28 million from the previous success bonus, totaling roughly $217 million. In contrast, Williams, finishing ninth, would earn $65.5 million in performance payments and $4.22 million from the previous success bonus, for a total of about $69.72 million. This means Mercedes earns over three times what Williams does, despite only finishing six spots higher.

The system heavily rewards historical and consistent success, leaving smaller teams with limited financial opportunities to close the gap.

Historic Payments and Legacy Bonuses

Ferrari’s historical bonus is a standout feature of F1’s prize structure. Unlike performance-based rewards, this payment is guaranteed regardless of where Ferrari finishes in the standings. For instance, in 2024, Ferrari placed second in the constructors’ championship, but its historical bonus, combined with other rewards, positioned it as the top earner - surpassing even the championship-winning team.

The previous success bonus also plays a significant role in amplifying financial disparities. Teams like Mercedes, with its streak of championships, and Red Bull, with strong performances from 2022 to 2024, continue to reap rewards from victories achieved years ago. This system ensures that past achievements provide financial benefits long after those successes are no longer recent.

The lack of transparency surrounding these payments makes it difficult for smaller teams to negotiate better terms or for stakeholders to advocate for reform. Without clear details on the formulas or payment breakdowns, it’s hard to determine whether the system promotes healthy competition or reinforces existing hierarchies. Essentially, the prize money structure operates on three levels: short-term rewards for current performance, medium-term rewards for sustained success, and enduring rewards for historical significance. Top teams benefit across all three levels, while smaller teams often struggle to gain traction in even one.

How Uneven Prize Money Affects Team Performance

The disparity in prize money directly impacts how teams perform on the track. When one team rakes in $251.44 million while another earns just $56.52 million, the 4.5x difference isn't just a number - it translates into real-world performance advantages. This financial gap shapes everything from research and development (R&D) to the overall competitiveness of a team.

Prize money powers R&D, and R&D drives lap times. Teams with budgets in the $140-160 million range can juggle multiple development projects, like wind tunnel testing and computational fluid dynamics simulations, all at once. On the other hand, teams operating on $60 million must make tough choices - prioritizing one initiative often means sacrificing another, whether it’s hiring experienced engineers or upgrading critical facilities.

Take the $75 million gap between McLaren's $132.9 million and Alpine's $57.9 million in performance-based payouts. That difference funds entire departments. It pays for advanced simulation tools that predict how a car will behave under different track conditions. It covers the salaries of specialized engineers who focus on tire strategy or energy management. It even allows teams to manufacture backup parts and test components without worrying about budget constraints.

Driver talent is another piece of the puzzle. Top drivers naturally gravitate toward teams with deeper pockets, leaving smaller teams to nurture younger, less experienced talent. While this occasionally results in standout performances, it usually reinforces the existing hierarchy. Without top-tier drivers and the resources to keep them, underfunded teams often fall further behind, both on and off the track.

Wealthier teams also have a built-in advantage when it comes to retaining talent. A skilled aerodynamicist at a lower-budget team might come up with groundbreaking solutions, but they’re constantly at risk of being poached by a top team offering double the salary and better resources. It’s a cycle: better facilities attract better engineers, who build faster cars, which earn more prize money, allowing the wealthier teams to pull even further ahead.

McLaren’s recent journey highlights the system's flaws. Despite winning the 2024 constructors' championship, McLaren's prize money was still significantly lower than Ferrari's. Why? Ferrari benefits from $63.3 million in guaranteed historical bonuses, a payout they receive regardless of their performance. Even a championship win wasn’t enough for McLaren to financially match Ferrari’s automatic windfall.

This financial inequality isn’t just about immediate competition - it creates a long-term infrastructure gap. Top teams can afford to invest in wind tunnels, advanced manufacturing equipment, and state-of-the-art testing facilities. These investments pay off for years, giving them a technical edge that smaller teams simply can’t match. For example, a team earning $200+ million can comfortably spend $50 million on a new wind tunnel, knowing future prize money will cover the cost. Meanwhile, a team earning $60 million can’t take that kind of financial risk; they’re stuck operating season-to-season, unable to plan for the long term.

Mercedes offers a clear example of how past success leads to sustained dominance. With $101.28 million from the previous success bonus pool alone, Mercedes starts each season with guaranteed funding that exceeds what some teams earn even in their best years. This financial cushion allows them to maintain development programs and keep top talent, even during challenging seasons.

The result of these financial disparities is a performance hierarchy that’s hard to disrupt. Occasionally, a midfield team might develop a standout aerodynamic innovation or make a strategic breakthrough that propels them up the grid - for a while. But without the financial muscle to sustain that momentum, they’re often overtaken as wealthier teams adopt and improve upon their innovations.

For lower-tier teams, the challenges are even steeper. Financial instability makes long-term planning nearly impossible. When prize money depends entirely on current-season results, one bad year can trigger a downward spiral. Less prize money forces budget cuts, which hurt development, leading to worse performance and even less prize money the following year. Teams like Alpine and Sauber, which lack historical bonuses, live on this precarious edge every season.

Adding to the problem is the lack of transparency in prize money distribution. Smaller teams don’t have a clear view of how payments are calculated, making it difficult to negotiate better terms or pinpoint areas where the system might be unfair. This opacity shields the current system from accountability and stifles efforts to push for reforms that could create a more level playing field.

What’s especially challenging is how the system rewards past success indefinitely. Ferrari’s $63.3 million historical bonus comes in regardless of where they finish in the standings. This guaranteed income provides financial stability, allowing top teams to take calculated risks and fund long-term projects. Meanwhile, smaller teams are forced to focus on short-term survival.

Challenges for Midfield and Lower-Tier Teams

The Midfield Squeeze

Midfield teams find themselves stuck in a tough financial loop. The gap in prize money between finishing fifth and tenth is a staggering $40.9 million annually. For instance, in 2025, Aston Martin earned $98.8 million, while Sauber only managed $57.9 million. Dropping even one position in the standings costs a team about $8.54 million, directly impacting their ability to invest in crucial areas like aerodynamics, simulation tools, and top-tier engineering talent.

Sauber's 2025 season highlights this struggle. With just $57.9 million in prize money, they faced competitors like Aston Martin, who had an additional $40.9 million to fund key departments like wind tunnel testing or CFD analysis. This forces midfield teams to make difficult choices - should they focus on improving their current season's performance, or save resources for future development?

Teams like Racing Bulls and Haas face similar challenges, earning $74.1 million and $82.6 million, respectively. Unlike top teams such as Mercedes, which can afford specialized departments for aerodynamics, power units, and race strategy, smaller teams often require their engineers to juggle multiple responsibilities. On top of that, these teams frequently lose their best talent to better-funded competitors offering more lucrative opportunities, widening the performance gap even further.

Take Williams, for example. Despite earning $65.5 million in prize money and an extra $4.22 million in historical bonuses, they still lag far behind McLaren, which brought in $132.9 million. This $63.2 million shortfall forces Williams into a constant state of catch-up, leaving little room to invest in both their current car and future technologies.

This financial struggle creates a vicious cycle. Teams that finish lower in one season earn less money, which limits their ability to develop a competitive car for the next season. Meanwhile, top teams continue to build on their financial advantages, making it nearly impossible for midfield teams to break out of their predicament. These challenges don’t just affect today’s teams - they also highlight the uphill battle any new entrants would face.

Barriers to Entry for New Teams

The financial struggles of midfield teams pale in comparison to the hurdles new teams face when trying to enter Formula One. A new team would start at the bottom of the prize money ladder, earning around $57.9 million in their first season. However, building a competitive F1 operation requires an initial investment of $300-500 million, plus annual operating costs of $150-200 million. This means new teams are almost guaranteed to operate at a loss for several years until they can establish a history of success to boost their payouts.

Even an exceptional debut - say, finishing as high as fifth and earning $98.8 million - would still leave a new team with an annual shortfall of about $51.2 million compared to their operating expenses.

On top of that, new entrants don’t receive any legacy bonuses or historical success payments. Established teams like Ferrari and Mercedes enjoy guaranteed historical bonuses of $63.3 million and $101.28 million, respectively, giving them a massive advantage over any newcomers.

There’s another financial hurdle: the anti-dilution fee. New teams must pay $200 million to existing teams to compensate for the reduced prize pool caused by adding more competitors. When you combine this fee with the enormous upfront and operational costs, only organizations with deep pockets - like major car manufacturers or sovereign wealth funds - have a realistic shot at entering the sport.

Unfortunately, these high entry barriers provide no relief for existing midfield and lower-tier teams. While a smaller grid might mean less competition for prize money, the same financial structure that discourages new teams also solidifies the current hierarchy, leaving little room for change.

Proposed Solutions to Reduce the Competitive Divide

Reworking Formula One's financial framework could create a more level playing field while still encouraging top-tier performance. A good place to start is revisiting legacy payments.

Revisiting Legacy Payments

Payments based on historical success, like Ferrari's bonus and the previous success payments, give long-established teams a financial head start each season. Gradually reducing these bonuses over three to five years could ease the transition while freeing up funds for fairer redistribution. For instance, Ferrari’s bonus could be reduced from 5% to 3% in the first year, then to 2%, and eventually phased out entirely. This would allow those funds to be reallocated in a way that benefits all teams.

The previous success bonus, which currently accounts for 20% of the prize fund (around $253.2 million), is another area ripe for reform. Under this system, championship results from up to a decade ago still count, giving teams like Mercedes $101.28 million for 24 historical points, while McLaren earns just $16.88 million from 4 points, even after winning the 2024 constructors' championship. By shifting to a rolling five-year performance window, only recent successes would be rewarded. Halving the bonus to 10% could free up $126.6 million, which could then be distributed more evenly - about $12–13 million per team. While legacy teams protected by the Concorde Agreement may resist such changes, a more competitive grid could attract more viewers, ultimately growing the total prize pool.

Creating a Prize Money Floor

Another immediate way to help lower-tier teams is by introducing a prize money floor. Setting this floor between $90 million and $100 million annually would ensure that every team has the resources needed to compete effectively. For example, increasing the payout for 10th place from $57.9 million to $90 million would give struggling teams an extra $32.1 million to invest in critical areas like aerodynamics and engineering.

At the same time, capping maximum payments for top teams would help balance the scales. Depending on the chosen floor, the gap between the highest and lowest payouts could shrink to about $33–43 million. This still rewards success but avoids creating an overwhelming advantage for the top teams. Redistributing $200–300 million from top earners to lower-tier teams could achieve this balance. With the prize pool growing - up 4% from $1.215 billion in 2023 to $1.266 billion in 2024 - this adjustment might simply mean top teams take a smaller slice of a larger pie.

Some critics might argue that a prize floor reduces the incentive to perform well. However, pairing it with enhanced performance-based bonuses ensures that higher finishing teams still earn more, while every team has a sustainable baseline to work from.

Rewarding Year-Over-Year Improvement

Currently, prize money is awarded based solely on finishing positions, which overlooks the efforts of lower-tier teams striving to improve. Introducing an improvement bonus pool - allocating 5% to 10% of the total prize fund (around $63 million to $127 million) - could reward teams that climb the standings from one season to the next. Bonuses could be distributed on a sliding scale, proportional to the degree of improvement.

For example, midfield teams like Haas, Racing Bulls, and Sauber currently receive $82.6 million, $90.2 million, and $74.1 million, respectively. If Haas were to move up from 7th to 5th place, they would not only earn the higher base payment for 5th but also qualify for an improvement bonus. To prevent teams from gaming the system, bonuses could be tied to averaged results over two seasons or specific milestones.

By eliminating legacy payments, establishing a prize money floor, and rewarding year-over-year improvement, Formula One could significantly narrow payout gaps and enhance competitiveness. The current gap between first and tenth place, which sits at $75 million, could shrink to $33–43 million. This still rewards excellence but gives every team a better shot at competing.

The real hurdle isn’t financial or technical - Formula One generates more than enough revenue to support these changes. The challenge lies in securing the political will. With the Concorde Agreement periodically renegotiated, stakeholders have a chance to prioritize long-term balance over short-term gains. These reforms could pave the way for a more competitive and exciting future for F1.

Conclusion: The Future of Competitive Balance in Formula One

Formula One stands at a crossroads. The current prize money system, distributing $1.266 billion annually, has exposed a glaring imbalance rooted in the Concorde Agreement. This structure has created a financial divide that directly impacts competition on the track.

The numbers paint a stark picture. Ferrari, Mercedes, and Red Bull collectively take home $661.38 million - an astonishing 52.2% of the total prize fund shared by all ten teams. This concentration of wealth allows these top teams to reinvest heavily in development, perpetuating their dominance and leaving smaller teams struggling to keep up.

Addressing this gap calls for practical, step-by-step reforms. Instead of scrapping performance-based rewards entirely, the focus should be on ensuring every team has the resources to compete meaningfully. Ideas like phasing out legacy payments, setting a minimum prize payout of $85–90 million, and incentivizing year-over-year improvement could go a long way in closing the $195 million funding gap between the top and bottom teams.

Financially, these changes are well within reach. With Formula One generating $3.6 billion in annual revenue and the prize pool growing by 4% from 2024 to 2025, the money is there. The real hurdle isn’t economic - it’s political. Teams benefiting from the current system have little motivation to support reforms, even though a more competitive grid could attract more fans, boost viewership, and increase overall revenue. The upcoming Concorde Agreement negotiations offer a critical chance to shift priorities toward leveling the playing field.

Fans crave a sport where all ten teams have a shot at podium finishes, not just the same three dominating race after race. Sponsors want to see their investments pay off in a competitive environment, and drivers thrive in a system where talent and strategy outweigh financial disparities.

Over its 75-year journey, Formula One has transformed from modest open-wheel races to a global spectacle generating billions. Yet, its prize money distribution remains tied to outdated practices, rewarding historical success more than current performance. The sport needs a system that reflects today’s reality - one that promotes competition, supports all teams, and gives every participant a fair shot at success.

The real question isn’t whether Formula One can afford these changes - it’s whether its stakeholders are willing to prioritize the sport’s long-term health over short-term financial gains.

FAQs

How does F1's prize money distribution affect smaller teams' competitiveness?

The way prize money is distributed in Formula One leans heavily in favor of the top-performing teams, creating a noticeable financial divide between them and the smaller teams. This gap makes it tough for less-funded teams to keep up, as they struggle to invest in cutting-edge technology, attract top-tier talent, and build cars that can truly compete on the track.

Meanwhile, the larger teams not only receive bigger prize payouts but also rake in additional income through lucrative sponsorship deals, making the divide even wider. To address this imbalance, some have proposed changing the prize money structure or enforcing stricter budget caps, giving all teams a more equal shot at competing.

How can the F1 prize money system be made fairer for all teams?

The way F1 prize money is distributed right now tends to benefit the top teams, widening the financial gap and making it tougher for smaller teams to stay competitive. To tackle this imbalance, some ideas have been put forward. One suggestion is to share a bigger portion of the revenue more equally across all teams. Another is to implement budget caps that would limit how much teams can spend, reducing the financial disparities. There's also the idea of rewarding teams for showing performance improvements, not just for their race results. These changes are designed to create a fairer competition and bring more excitement to the championship.

How do historical bonuses for teams like Ferrari and Mercedes impact new teams entering Formula One?

Historical bonuses, like those awarded to Ferrari and Mercedes, are financial perks tied to their enduring presence and achievements in Formula One. These bonuses acknowledge the impact of legacy teams on the sport, but they also tilt the financial scales heavily in favor of these long-established teams.

This imbalance poses a challenge for new teams. With fewer resources at their disposal, newcomers must stretch their budgets to try and compete with teams that not only have decades of experience but also enjoy additional funding. Tackling this issue could pave the way for a more level playing field, encouraging fairer competition across the grid.