Constructor Turnover in F1: Patterns Across Decades

How F1 constructors changed from the 1950s to today — technical revolutions, financial pressures, manufacturer takeovers, and the stabilizing effect of the budget cap.

Formula 1 has seen 172 constructors participate since 1950, but only a few have endured long-term. Why? High costs, rapid technical changes, and shifting ownership often force teams to exit or rebrand. Ferrari remains the sole constant, while others like Mercedes and Alpine trace their origins to older teams like Tyrrell and Toleman.

Key takeaways:

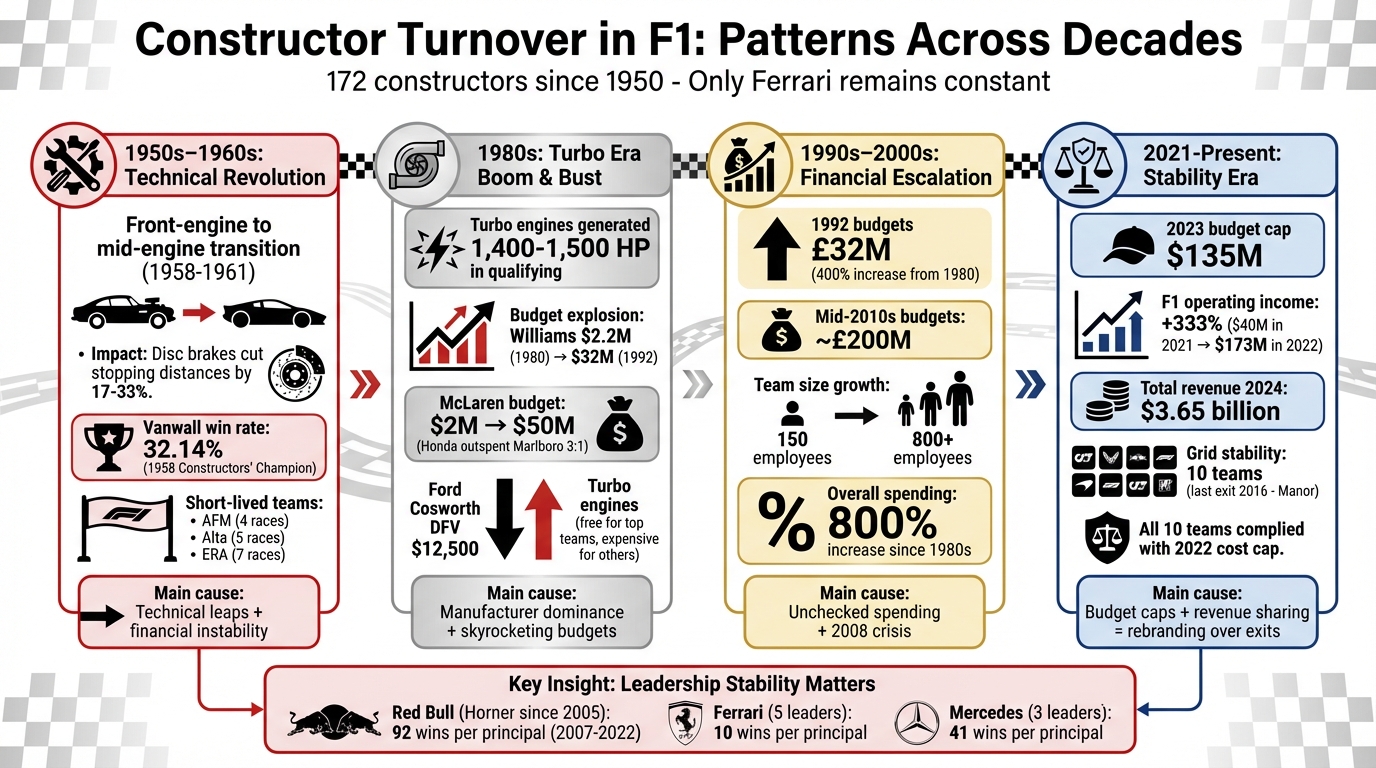

- 1950s-60s: Technical leaps (e.g., mid-engine cars) and financial instability caused frequent team exits.

- 1980s Turbo Era: Manufacturer dominance and skyrocketing budgets pushed smaller teams out.

- Modern Era: Budget caps and revenue sharing stabilized the grid, with rebranding replacing team exits.

Today’s F1 grid reflects a shift toward financial stability, with fewer teams leaving and more focus on rebranding existing ones.

F1 Constructor Turnover Patterns Across Decades: 1950s to Present

50 years of Formula 1 Constructors History (1970-2020)

The Early Years: 1950s-1960s

The first two decades of Formula 1 were a whirlwind of technical advancements and financial challenges. Teams either adapted to the rapid changes or disappeared from the grid entirely. It was a time when a single breakthrough could redefine the sport, leaving others scrambling to catch up.

Technical Changes and Early Exits

One of the most transformative shifts in this era was the move from front-engine to mid-engine car designs. This change wasn’t just a tweak - it was a revolution. In January 1958, Stirling Moss drove the mid-engined Cooper T43 to victory at the Argentine Grand Prix for the privateer Rob Walker Racing Team. It was the first World Championship win for a rear-mid engine car, proving that superior handling could outmatch raw horsepower from the front-engine giants like Maserati.

"The victory proved that superior chassis dynamics and low polar moment of inertia could definitively overcome the horsepower advantages held by the larger, better-funded factory teams." – F1 Mavericks

Why did mid-engine cars dominate? Their design lowered the polar moment of inertia, making them more agile in corners and improving traction over the rear axle. By 1961, front-engine cars were history in competitive F1. Teams like Cooper and Lotus, often dismissed as "garagistes" by traditionalists, outmaneuvered bigger factory-backed teams stuck with outdated technology.

Other innovations were just as disruptive. Take disc brakes, for example. Vanwall introduced them to F1 in 1957, and they were a game changer. Compared to drum brakes, disc brakes cut stopping distances by 17–33%, giving drivers a significant edge. Stirling Moss showcased this advantage at the 1957 British Grand Prix, where his Vanwall's superior braking helped secure victory. That same year, Vanwall’s thermal management systems prevented brake fade, a common issue for drum-braked competitors. This technological leap helped Vanwall win the first Constructors' Championship in 1958, with an impressive win rate of 32.14% across 28 starts.

Regulations also played a role in reshaping the sport. In 1954, the FIA reduced engine capacity for naturally aspirated engines from 4.5 liters to 2.5 liters, forcing teams to rethink their power units. Then, in 1958, teams had to switch from alcohol-based fuels to aviation gasoline, which required detuning engines to avoid knocking. These constant changes created a survival-of-the-fittest environment, where only the most adaptable teams thrived. Yet, even the best technical strategies couldn’t save teams struggling with financial instability.

Financial Barriers for Smaller Teams

While technical challenges weeded out some teams, financial struggles proved even more fatal. The 1950s and early 1960s were littered with one-off entries from constructors who simply couldn’t afford to stay competitive. Teams like AFM (4 races, 1952–1953), Alta (5 races, 1950–1952), and ERA (7 races, 1950–1952) are prime examples of operations that faded fast.

For many smaller teams, the customer chassis model was a lifeline. Before 1981, constructors could sell their chassis to privateers, allowing smaller outfits to compete without the massive expense of designing and building their own cars. Rob Walker Racing Team used this approach to great effect, purchasing cars from Cooper and Lotus to secure their first wins.

In contrast, factory-backed teams like Ferrari, Mercedes, and Alfa Romeo had the advantage of larger budgets and vertical integration. Ferrari, for instance, has entered 1,124 Grand Prix races, a testament to its financial and organizational strength. Smaller teams like Connaught (1952–1959) and HWM (1951–1955) couldn’t keep up and folded within a decade.

During this period, widespread commercial sponsorship was almost nonexistent. Most teams operated on shoestring budgets, relying on modest support from oil and tire companies or the personal wealth of team owners. Combined with the relentless pace of technical evolution, these financial pressures created a high turnover rate among constructors. This turbulent foundation set the stage for the competitive dynamics that would define Formula 1 in the years to come.

The Turbo Era and 1980s: Boom and Bust Cycles

The 1980s were a game-changing decade for Formula 1, marked by the rise of turbocharged engines and the financial challenges that followed. It all began in 1977 when Renault leveraged the "equivalency factor" regulations for forced induction, igniting a turbo revolution that reshaped the sport. This era brought record-breaking performance but also created financial hurdles that changed the competitive landscape.

The Impact of Turbo Engines

Turbo engines drew major manufacturers like BMW, Honda, Alfa Romeo, and Porsche (via TAG) into Formula 1, shifting the sport's focus from independent teams to those backed by corporate giants. The performance gains were staggering - by the mid-1980s, turbocharged engines were generating between 1,400 and 1,500 horsepower in qualifying trim. One standout moment came in 1985 when Keke Rosberg, driving the Williams FW10, set a qualifying lap record at Silverstone with an average speed of over 160 mph - a record that held for nearly two decades.

But this power came with a hefty price tag. Before the turbo era, smaller teams could buy a Ford Cosworth DFV engine for $12,500. Turbo engines, however, required advanced materials, cutting-edge electronics, and specialized fuels, making them prohibitively expensive. Leading teams like McLaren-Honda and Brabham-BMW received these engines for free, along with significant financial backing from their manufacturers.

The financial impact was profound. Williams’ budget skyrocketed from $2.2 million in 1980 to $32 million by 1992. Similarly, McLaren’s budget grew from around $2 million to $50 million, with Honda reportedly outspending Marlboro three-to-one.

"Other F1 teams that failed to recognize the Dennis-led scale change - even those like Lotus and Brabham with proud histories - would fall by the wayside if they didn't borrow from the future to expand, to keep up."

– Motor Sport Magazine

The turbo era also attracted smaller constructors like AGS, Zakspeed, Coloni, and EuroBrun, drawn by the sport’s increasing visibility. However, many of these teams struggled to keep up with the rising costs and quickly faded away.

Regulation Changes and Grid Contraction

As financial pressures mounted and the gap between teams widened, regulatory changes became inevitable. In 1989, the FIA banned turbo engines, mandating the use of 3.5-liter naturally aspirated engines. This forced teams to overhaul their technical strategies, with devastating consequences for some.

Take Williams, for example. After losing its Honda turbo partnership at the end of 1987, the team fell from winning the Constructors' Championship in 1987 to finishing 7th in 1988 while running underpowered Judd V8 engines. During this transitional period, naturally aspirated engines couldn’t compete with turbocharged units, leading the FIA to introduce separate trophies for drivers and constructors.

"The total spend increased vastly during the first turbo era, but for the teams the turbo engines themselves added cost only to those smaller outfits that were having to buy them commercially rather than being supplied free."

– Motor Sport Magazine

The turbo era didn’t just redefine race performance - it also accelerated the turnover of constructors. Smaller teams struggled to stay afloat, and the sport began to see the kind of consolidation that would shape its future in the decades to come.

The Modern Era: 1990s-Present

Financial and Regulatory Challenges

The 1990s brought a dramatic rise in Formula 1 budgets. In 1992, title-winning teams operated with £32 million - a staggering 400% increase compared to 1980. By the mid-2010s, those budgets had ballooned to around £200 million. Teams expanded rapidly, growing from 150 to over 800 employees, with overall spending surging 800% since the 1980s. This relentless financial escalation created immense pressure, especially for smaller teams struggling to compete for a shrinking share of revenue. The 2008 global economic crisis added to the strain, prompting cost-cutting measures like engine freezes and restrictions on testing to manage expenses.

The introduction of the 2021 budget cap brought a seismic shift to F1's financial landscape. By 2023, the cap was set at $135 million, though key expenses like driver salaries, marketing, and the salaries of the three highest-paid staff members were excluded. This change transformed F1 teams from notorious "money pits" into profitable ventures. Mid-field teams, once perpetually in the red, now have the chance to break even or even turn a profit. Formula 1's overall operating income skyrocketed by 333%, climbing from $40 million in 2021 to $173 million in 2022. Meanwhile, total revenue reached an all-time high of $3.65 billion in 2024.

These economic adjustments reshaped the sport, paving the way for manufacturers to take a leading role and redefine team structures.

The Rise of Manufacturer Teams

As financial pressures mounted, manufacturers began to reshape the dynamics of F1. Companies like Renault, BMW, Mercedes, and Toyota entered the sport with massive budgets, setting new financial benchmarks that independent teams found almost impossible to match. Honda’s partnership with McLaren in 1988, where it outspent Marlboro by a ratio of 3:1, marked a turning point.

"One of the biggest drivers of the massive growth between the end of the '70s and the beginning of the '90s was Ron [Dennis]... he realised the only way to do this was to outspend Ferrari"

Rather than starting from scratch, manufacturers often acquired existing teams. For example, in December 2009, Mercedes-Benz purchased Brawn GP, a team that had itself risen from the remains of Honda earlier that year. Under the leadership of Ross Brawn and later Toto Wolff, this team transformed into a dominant force, claiming eight consecutive constructors' titles between 2014 and 2021. Similarly, Lawrence Stroll's consortium acquired Force India in 2018, eventually rebranding it as Aston Martin in 2021.

This trend of acquisition over new entries became the norm. Well-established infrastructures, like those at Enstone or Brackley, continued to thrive despite frequent changes in ownership and branding. Independent teams either partnered with manufacturers or were bought by wealthy investors, as seen in Dorilton Capital's purchase of Williams.

Consolidation and Stability in Recent Years

Unlike earlier decades, marked by frequent team entries and exits, the modern era has seen a much more stable grid. With regulated budgets and structured revenue sharing, the number of teams has stabilized at 10, with the last collapse occurring in 2016 when Manor exited the sport. This is a stark contrast to 1989, when 39 cars were entered for races, though only 26 were allowed to start. Since 1950, 172 different constructors have participated in at least one race, but today’s F1 is more about rebranding than entirely new entries.

The budget cap has been a key driver of this stability. Stefano Domenicali, CEO of Formula One Group, explained:

"We pass through years where we have a dominant team and a dominant driver... this is something we try to rectify with regulations... for example, with the introduction of the budget cap"

In fact, all 10 teams complied with the 2022 cost cap regulations, signaling a new era of financial discipline. Prize money distribution has also become more streamlined under the Concorde Agreement. Beyond racing, teams now generate additional revenue by applying their engineering expertise to other industries, such as medical devices and America's Cup yachts, through "Applied Technology" divisions.

Key Patterns and Their Effects on Competition

The financial pressures within Formula 1 have historically led to significant upheavals. Teams like Lotus and Brabham, once competitive forces, were unable to keep up with rising costs and ultimately folded under the strain. Ownership changes have also played a major role in shaping the sport. A prime example is the current Aston Martin team, which began as Jordan in 1991. Over the years, it went through various identities - Midland, Spyker, Force India, and Racing Point - before its rebranding in 2021. Manufacturer withdrawals added to the instability, with BMW leaving Sauber and Honda exiting the sport just before the 2009 season. These events not only disrupted the grid but also set the stage for shifts in leadership and the involvement of new manufacturers.

Amid this turbulence, stable leadership has emerged as a critical factor in achieving success. Teams with consistent leadership tend to perform better over time. Between 2007 and 2022, Red Bull, under Christian Horner, averaged 92 wins per team principal. In contrast, Ferrari, which cycled through five different leaders during the same period, managed only 10 wins per principal. Mercedes, with three leaders in that timeframe, achieved an average of 41 wins per principal. F1 analyst Alianora La Canta highlighted the importance of stability:

"Consistent success is likely to elude a team that keeps chopping and changing its leader, and that such a team will inevitably underperform relative to its circumstances".

Regulatory changes have also played a significant role in leveling the playing field. The introduction of the 2021 budget cap marked a turning point by curbing the unchecked financial spending that once created massive performance gaps. This cap has allowed mid-tier teams to operate profitably while investing in long-term development, reducing the risk of financial collapse.

The focus in technical development has shifted from sheer spending to efficiency. This change has encouraged more balanced competition across the grid and replaced the boom-and-bust cycles that previously defined team turnover. Smaller teams now have the opportunity to pursue sustained development projects, fundamentally altering the sport's competitive dynamics.

Conclusion: Lessons from Constructor Turnover in F1

The story of constructor turnover in Formula 1 underscores the importance of financial stability and steady leadership for long-term success. Take Red Bull, for example - under Christian Horner’s leadership since 2005, the team achieved an impressive 92 wins per team principal between 2007 and 2022. Compare that to Ferrari, which cycled through six different team leaders over the same 15 years. This revolving door of leadership highlights the difficulties that come with constant change and sets the stage for understanding how regulations have influenced the sport.

One of the most impactful regulatory changes came with the introduction of the 2021 Cost Cap. By limiting spending, the focus shifted from sheer financial muscle to operational efficiency. The results were striking: Formula 1's operating income soared by 333%, jumping from $40 million in 2021 to $173 million in 2022. As Stefano Domenicali, CEO of Formula One Group, put it:

"We try to rectify with regulations... for example, with the introduction of the budget cap".

Today, turnover in F1 often means rebranding rather than complete exits. A great example is the team now known as Aston Martin, which has competed under various names, including Jordan, Midland, Spyker, Force India, and Racing Point. This evolution reflects the immense value of F1 entry slots, which continue to attract investors and manufacturers. These changes signify a shift in how teams approach the sport, pointing to a broader evolution that will shape F1's future.

From the early days of teams leaving the grid entirely to the modern trend of rebranding, constructor turnover has played a crucial role in reshaping F1's competitive landscape. Moving forward, the sport's stability will rely on balancing technical progress, financial health, and fair competition. The Cost Cap has already helped reduce the boom-and-bust cycles, creating a more level playing field for smaller teams. With total revenue reaching $2.573 billion in 2022 - a 20.5% increase from the previous year - F1 now has the financial foundation to maintain a stable, competitive grid for years to come.

FAQs

Why has Ferrari remained a constant in Formula 1 while other teams have come and gone?

Ferrari’s presence in Formula 1 is more than just participation - it’s a testament to its rich history, distinctive brand, and steadfast dedication to the sport. As one of the founding teams since F1's debut in 1950, Ferrari has become synonymous with racing excellence, maintaining its place as a symbol of motorsport heritage despite shifts in performance, leadership, and competition over the years.

What keeps Ferrari at the forefront? A major factor is its unwavering financial commitment and drive for technological advancement. By consistently channeling resources into car development and cutting-edge technology, Ferrari has managed to stay relevant, even during times when victories were harder to come by. Beyond the track, Ferrari’s passionate global fanbase and its iconic status in motorsport further cement its role as an integral part of Formula 1.

While other teams have faced challenges like financial struggles, unstable leadership, or sponsorship troubles - often resulting in their departure - Ferrari’s unique blend of legacy, resilience, and strategic foresight has allowed it to remain a dominant and enduring force in the sport.

How have budget caps impacted F1 teams' finances and competition?

Budget caps have brought a new dynamic to Formula 1 by placing limits on team spending, creating a more balanced and competitive playing field. These caps restrict how much teams can invest in areas like staffing, technology, and car development, pushing them to make smarter decisions about where to allocate their resources.

This shift has leveled the playing field, giving smaller teams a fighting chance against historically dominant, wealthier teams. For instance, Haas has reported better profitability by streamlining their expenses under the cap. On the flip side, teams like Red Bull now face the challenge of managing their high revenues while staying within these tighter financial boundaries.

In essence, budget caps are reshaping the sport, encouraging teams to innovate under constraints while narrowing performance gaps across the grid.

How did the turbo era affect smaller F1 teams?

The turbo era in Formula 1, which stretched from the late 1970s to the mid-1980s, was a time of incredible engine innovation. Turbocharged engines brought a level of performance that had never been seen before, but these advancements came with a hefty price tag. Developing and maintaining these engines required both significant financial backing and technical expertise.

Big-name teams like Ferrari and Renault thrived during this period. With their deep pockets and access to cutting-edge technology, they were able to dominate the grid. On the other hand, smaller teams found themselves struggling. The rising costs and technical demands of turbo engines often left them unable to compete on equal footing. Many fell behind in performance, while others faced financial difficulties so severe that they had to withdraw from the sport altogether.

This era didn’t just showcase the power of turbocharged engines - it also underscored the growing gap between the well-funded teams and those with fewer resources. It became clear that success in Formula 1 was increasingly tied to a team's ability to invest heavily in development and innovation.