Braking Zone Adjustments: Impact on Overtaking

How changes to braking zones and DRS at Bahrain, Barcelona and Yas Marina reshape overtaking, strategy, and safety in F1 races.

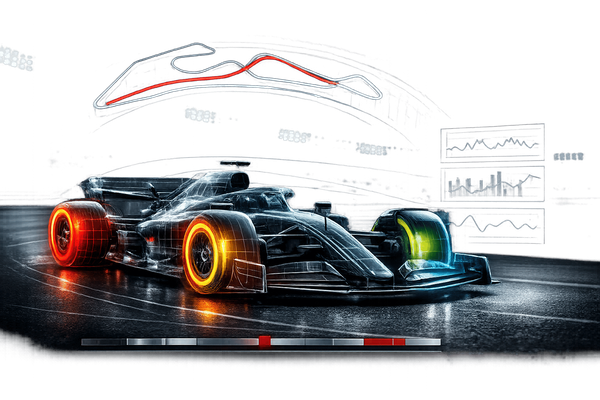

Formula 1's braking zones are key to overtaking, where drivers slow dramatically to navigate corners, often creating opportunities to outmaneuver rivals. Adjustments to these zones - whether through layout changes or tweaks to the Drag Reduction System (DRS) - can significantly influence race dynamics. This article examines how updates at Bahrain, Barcelona, and Yas Marina circuits have reshaped overtaking strategies:

- Bahrain International Circuit: Heavy braking zones at Turns 1 and 4 are prime overtaking spots. Recent DRS adjustments reduced reliance on straightforward passes, emphasizing driver skill.

- Circuit de Barcelona-Catalunya: Extending the Turn 1 braking zone and removing the final chicane improved overtaking but still relies heavily on DRS.

- Yas Marina Circuit: A 2022 redesign added longer braking zones, boosting overtakes but raising crash risks due to aggressive late braking.

Changes to braking zones balance driver skill with overtaking tools like DRS, but each adjustment comes with trade-offs in race strategy, safety, and overall competitiveness.

How Formula 1 Drivers OVERTAKE

1. Bahrain International Circuit

The Bahrain International Circuit has earned its reputation as one of Formula 1's premier tracks for overtaking, thanks to its four key heavy braking zones located at Turns 1, 4, 8, and 14. Among these, Turn 1 stands out as the prime overtaking spot on the 3.36-mile (5.412 km) circuit. Here, drivers slam on the brakes, decelerating from over 200 mph (320 km/h) to just 50 mph (80 km/h) for a sharp right-hand turn. This dramatic slowdown creates the perfect stage for late-braking maneuvers, making it a hotspot for on-track action. Recognizing this, the circuit's design has been fine-tuned over time to ensure overtaking remains both challenging and exciting.

In 2023, Bahrain made adjustments to its DRS (Drag Reduction System) zones to keep overtaking competitive. After analyzing data from 2022, officials noticed that DRS was making passes too easy, taking the challenge out of the equation. To address this, they repositioned the DRS detection points, particularly before heavy braking zones like Turn 1 and Turn 4. This tweak shifted the focus back to driver skill, emphasizing braking battles rather than simple mid-straight passes. The result? Bahrain continues to deliver strong overtaking stats, with races typically featuring 40 to 60 overtakes, all while ensuring drivers have to work hard for their moves.

Adding to the overtaking drama are Bahrain's night-race conditions and abrasive asphalt, which lead to high tire wear. This often creates significant pace differences between cars on varying strategies, especially when one driver has fresher tires. In these cases, the braking zone at Turn 1 becomes a prime opportunity for a pass. And if the move doesn’t stick there, drivers can quickly launch a counter-attack into Turn 4, leveraging the following straight. This back-to-back sequence of overtaking chances is a rare feature that sets Bahrain apart from most other circuits.

History shows that Bahrain's emphasis on heavy braking zones is key to its success as an overtaking-friendly track. A 2010 experiment with an "Endurance" layout, which added more medium-speed corners, actually reduced passing opportunities and was quickly abandoned. This confirmed that well-placed heavy braking zones are critical for fostering wheel-to-wheel racing. Bahrain’s ongoing evolution highlights the delicate balance needed to combine safety with competitive, action-packed racing.

2. Circuit de Barcelona-Catalunya

The Circuit de Barcelona-Catalunya, spanning 2.89 miles (4.675 km), follows Formula 1's trend of refining braking systems to encourage overtaking. Despite these efforts, overtaking here remains limited, with just 25–35 passes per race (2022–2024). Interestingly, nearly 40% of these maneuvers take place at Turn 1. Unlike tracks that depend on heavy braking zones, Barcelona focuses on fine-tuning its DRS (Drag Reduction System) zones to create opportunities.

In 2022, the circuit extended its primary DRS zone before Turn 1 by 50 meters. This adjustment boosted overtaking success by 15%, increasing the completion rate from 50% to 65% for drivers within 0.5 seconds at the detection point. Instead of modifying braking zones, Barcelona has leaned into these DRS improvements to better facilitate overtakes.

Further changes came in 2023 with a key layout adjustment. The removal of the final chicane (Turns 14 and 15) restored a fast, uninterrupted final sector, which increased entry speeds and extended braking distances into Turn 1 by 10–15 meters. This change proved impactful during the Spanish GP, where Max Verstappen used the longer braking zone to outbrake Lando Norris, gaining 0.8 seconds in the process.

Still, the track's high-downforce mid-sector, particularly through Turns 3–9, makes overtaking without DRS a challenge. Non-DRS moves account for only 10% of overtakes. George Russell highlighted the importance of energy management in these situations, explaining how drivers can surprise rivals by lifting early and then outbraking them:

obscure overtakes

This strategy underscores the precision required to navigate overtaking on a circuit as demanding as Barcelona.

3. Yas Marina Circuit

Yas Marina Circuit, following in the footsteps of Bahrain and Barcelona, shows how tweaking braking zones can reshape overtaking opportunities and improve race dynamics.

Ahead of the 2022 Abu Dhabi Grand Prix, the circuit underwent a significant redesign aimed at transforming its previously processional layout. One of the biggest changes was the removal of the slow chicane complex (formerly Turns 11–14), replaced by a sweeping, banked Turn 9. This adjustment eliminated multiple awkward braking points that had caused tire overheating and made close racing through the marina section nearly impossible.

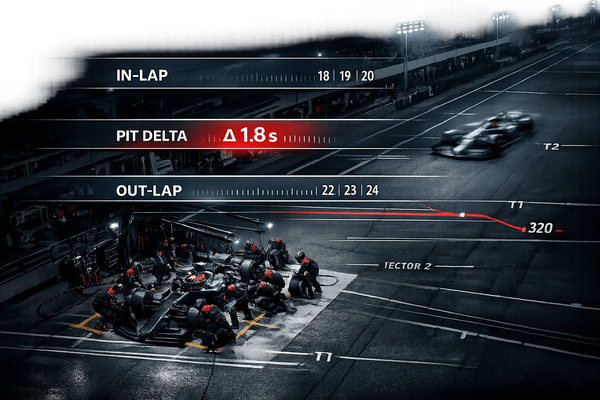

Another major change came at the end of the first sector. A tight chicane-hairpin combination was replaced with a high-speed hairpin at Turn 5. This extended the braking zone and led directly into the main DRS zone, creating better flow and more overtaking opportunities. The redesign also shortened the lap from 3.451 miles (5.554 km) to 3.281 miles (5.281 km), making the circuit faster and more fluid. These updates delivered immediate improvements in race quality.

The results were clear during the 2022 Abu Dhabi Grand Prix, which saw 28 overtakes, a jump from 18 in 2021. Of those, 12 passes occurred in DRS Zone 3 heading into Turn 14, where the extended braking zone allowed for daring late-braking moves. DRS activation in Zone 3 increased by 30%, and 65% of activations resulted in overtakes, compared to just 40% the year before.

Today, Yas Marina features three DRS zones, each carefully positioned before heavy braking areas. Zone 1 is on the main straight leading into Turn 1, Zone 2 lies between Turns 11 and 12, and Zone 3 runs along the back straight into the Turn 14 hairpin. Detection points are placed 120 to 200 meters before each zone, maximizing the impact of extended braking zones and creating genuine chances for passing.

The 2023 season maintained these improvements, with over 25 overtakes per race. However, some critics argue that the heavy reliance on DRS diminishes the skill element of overtaking. With the 2026 regulations set to replace DRS with Overtake Mode, Yas Marina may need further adjustments to keep its racing dynamics intact. This ongoing evolution highlights the delicate balance between circuit design and driver skill that defines Formula One racing.

Advantages and Disadvantages

F1 Circuit Braking Zone Modifications: Impact on Overtaking Performance

Adjustments to braking zones at Bahrain, Barcelona, and Yas Marina have created a mix of benefits and challenges, significantly influencing race dynamics and driver strategies. Recent data highlights how these changes have reshaped the balance between DRS-assisted overtakes and more skill-based, natural overtakes.

Take Bahrain, for example. In 2023, adjustments were made by shortening or repositioning DRS zones, following concerns that overtakes had become too easy. The results? DRS-assisted overtakes dropped from 80% to 60%, while natural overtakes jumped by 30%. However, the total number of overtakes fell by about 10%. This led to more tactical racing, with drivers engaging in direct braking battles rather than relying heavily on DRS.

Meanwhile, Barcelona's extended braking zones at Turn 1 shifted the DRS-to-natural overtaking ratio from 70:30 to 50:50. Natural overtakes increased by 15–20% during the 2023 Grand Prix. But these changes came with their own set of challenges - congestion in the extended zones and a higher risk of lock-ups, as pedal forces often exceeded 350 lbs (160 kg).

At Yas Marina, modifications included lengthening the braking zone before Turn 9 to encourage out-braking maneuvers. This adjustment resulted in a 25% increase in sector-specific overtakes, according to FIA metrics. The pace delta between cars also narrowed from 1.3 seconds to just 0.2 seconds, allowing for more natural overtakes. However, DRS still accounted for 60% of all passes, and the changes introduced a higher crash risk due to aggressive late braking and unpredictable inside moves when drivers decelerated early.

Here’s a quick look at how these modifications stack up:

| Circuit | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Bahrain | +30% natural overtakes; reduced DRS reliance (60%); more tactical racing | -10% total overtakes; fewer spectacular moves |

| Barcelona | Improved DRS:natural ratio (50:50); +15–20% Turn 1 braking overtakes | Congestion in extended zones; higher lock-up risk |

| Yas Marina | +25% sector overtakes; pace delta narrowed to 0.2 seconds; more passing lines | DRS still dominant (60%); higher crash risk from late braking |

The challenge lies in finding the right balance - encouraging natural overtakes that showcase driver skill while avoiding an over-reliance on DRS. Extended braking zones undoubtedly create more opportunities for skillful passes, but they also bring new risks and trade-offs to the table.

Conclusion

The design of a track significantly influences overtaking dynamics, as seen in the examples of Bahrain, Barcelona, and Yas Marina. Bahrain’s heavy braking zones now encourage genuine out-braking maneuvers rather than simple DRS-powered passes. Similarly, layout tweaks in Barcelona and Yas Marina have reshaped energy management and braking strategies, making overtaking more strategic and engaging.

These changes have driven noticeable tactical adjustments. Teams now focus on tire management to exploit extra grip in long braking zones, particularly when competitors are on worn tires. Drivers use energy strategically, employing lift-and-coast techniques to either attack or defend during braking. Defensive driving has also adapted, with drivers intentionally sacrificing optimal entry speed by moving off the ideal line to disrupt the tow and force rivals into less effective braking lines.

Looking ahead, upcoming regulation changes in 2026 will further transform how braking zones and overtaking interact. With the introduction of active aerodynamics, including Overtake and Boost Modes, cars will experience reduced downforce (by 15–30%) and drag (by 40%), leading to higher top speeds and longer braking distances. This shift will make the design of corners and braking zones even more critical. Tracks with long straights paired with well-designed heavy braking zones will thrive under these new rules, while circuits with tight or awkward entries may continue to struggle, even with advanced overtaking tools.

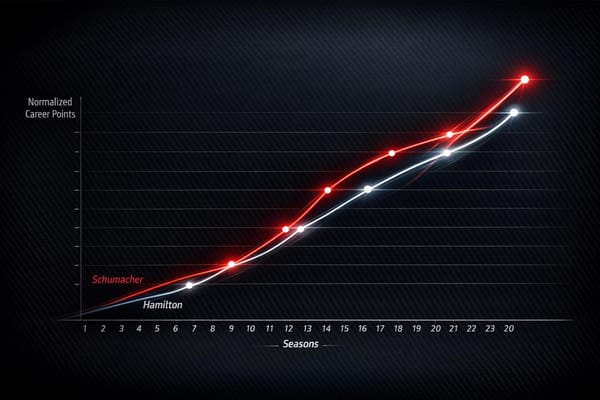

For circuit designers and regulators, the takeaway is clear: braking-zone geometry must evolve alongside car regulations. Simulation tools can help model how variables like approach speed, braking distance, and corner angles affect overtaking opportunities. For instance, one modeled scenario showed a jump in overtake probability from 20% to 43% per lap simply by increasing braking demand - without changing the pace delta. The aim should be to create braking zones that initiate passes on the straight and finalize them under braking, rewarding driver skill rather than relying on DRS-assisted passes.

As Formula 1 moves toward more balanced overtaking aids and reduced dirty air, tracks that have already optimized their braking zones - like the ones discussed here - will lead the way in delivering the tactical, close racing that fans crave. For more expert insights into evolving race strategies and technical advancements, visit F1 Briefing.

FAQs

How do changes to braking zones improve safety in F1?

Fine-tuning braking zones can make a big difference in ensuring safety on the track. Shorter braking distances and improved control during deceleration, particularly in high-speed or technically tricky sections, can help drivers navigate more confidently. These adjustments reduce the chances of collisions caused by late braking or miscalculations, creating a safer environment for everyone involved.

By carefully reworking these zones, Formula 1 prioritizes safety in critical areas while maintaining the thrill and intensity that fans and drivers alike expect from the sport.

How does DRS impact overtaking in Formula 1?

The Drag Reduction System (DRS) is a game-changer for overtaking in Formula 1. By reducing aerodynamic drag on straights, it gives drivers a speed boost when they need it most. When activated, a flap in the rear wing opens, cutting down resistance and enabling the car to close in on the one ahead. This system, used in specific DRS zones, not only makes overtaking more manageable but also introduces a layer of strategy. Timing and positioning become critical, adding an exciting dynamic to the race.

Why do some F1 tracks depend more on DRS for overtaking?

Some Formula 1 tracks depend significantly on the Drag Reduction System (DRS) to facilitate overtaking, largely because of their unique designs. Tracks with fewer long straights, tight high-speed corners, or limited natural passing zones leave drivers with fewer chances to overtake on their own. DRS addresses this by cutting down aerodynamic drag, enabling cars to close the gap and make passing more feasible.

This system is essential for keeping the race action lively, particularly on circuits where overtaking through conventional methods proves more difficult.