Carbon Fiber Monocoque: F1 Safety Revolution

Carbon fiber monocoques transformed F1 safety—lightweight, stronger survival cells with Kevlar/Zylon layers and HALO integration, proven in high-speed crashes.

The carbon fiber monocoque, introduced in 1981, transformed Formula 1 safety by creating a lightweight yet incredibly strong "survival cell" for drivers. This design replaced outdated metal chassis, which lacked the ability to absorb crash forces effectively and often endangered drivers. The monocoque, made from carbon fiber, is twice as strong as steel but five times lighter, with unmatched energy absorption properties (40–70 kJ/kg compared to steel's 12 kJ/kg).

Key milestones include:

- John Watson's 1981 crash: Proved the monocoque's durability when he survived a 140 mph crash with minor injuries.

- Material improvements: Kevlar and Zylon layers added to prevent penetration and enhance safety.

- Modern advancements: HALO devices now integrate with monocoques, protecting drivers from head injuries.

Today, F1 monocoques weigh just 35 kg yet withstand massive forces, making them the foundation of driver protection. This evolution highlights Formula 1's commitment to safety through continuous material and design innovations.

F1 Firsts: Carbon Fibre Monocoques

Metal Chassis Before Carbon Fiber

Before the 1980s, Formula One cars were built using welded steel or aluminum structures that provided only basic protection for drivers. Early models relied on simple sheet metal frames, but by the late 1950s, teams shifted to tubular spaceframe designs. These involved welding steel or aluminum tubes into a lattice-like framework, offering greater rigidity compared to sheet metal. While this was a step forward for its time, it soon became clear that these designs had serious limitations in both safety and performance.

"Before the monocoque, F1 cars were built around frames of welded steel or aluminum that provided a rudimentary shell around the driver."

– Lee Parker, Staff Writer, Formula One History

Structural Problems with Metal Chassis

Despite the introduction of aluminum monocoques, metal chassis designs still suffered from major flaws that impacted both safety and performance. One of the biggest issues was their inability to absorb energy effectively during crashes. The tubular spaceframe design, while innovative, had uneven force distribution. In the event of a collision, individual tubes could buckle or even puncture the cockpit, putting drivers at extreme risk.

Another problem was the weight-to-strength ratio. Adding more material to improve safety often resulted in heavier cars, which negatively affected speed and handling on the track. These compromises left teams searching for better solutions as the demands of the sport grew.

Safety Concerns in the 1960s and 1970s

The structural weaknesses of metal chassis weren't just a performance issue - they had deadly consequences. The 1960s and 1970s were particularly grim decades for Formula One, with frequent driver fatalities highlighting the dangers of these designs. As engine power increased and speeds climbed, the protective capabilities of steel and aluminum frames proved inadequate.

During crashes, these structures often crumpled too quickly, failing to decelerate the driver safely and transferring dangerous g-forces directly to the cockpit. Additionally, the risk of penetration was severe. Suspension components or sections of the chassis itself could pierce the cockpit, causing catastrophic injuries. It wasn't until later advancements - such as the introduction of Kevlar layers in composite designs - that this hazard was addressed.

These tragic realities underscored the urgent need for a material that could create a safer "survival cell" around the driver. This need ultimately drove the sport toward the carbon fiber revolution, which began reshaping Formula One safety in 1981.

McLaren MP4/1: First Carbon Fiber Monocoque in 1981

John Barnard faced a challenge: he needed an ultra-narrow monocoque to optimize the Venturi tunnels for ground effect aerodynamics. Aluminum proved too flexible, and steel was far too heavy. When conventional suppliers couldn't meet the demand, Barnard turned to Hercules Aerospace in Utah, a company specializing in advanced aircraft materials. This collaboration marked the beginning of a new era in manufacturing.

MP4/1 Design and Development

Through this partnership, McLaren developed a revolutionary technique for constructing the chassis. Layers of carbon fiber were carefully molded around a mandrel and then autoclaved, creating a single, rigid structure.

The design was a sandwich structure, featuring an inner carbon skin, an aluminum honeycomb core, and an outer carbon skin. Engineers used unidirectional carbon fiber prepreg tape, aligning fibers to handle directional forces efficiently. This approach resulted in a chassis that was more than twice as stiff as its aluminum counterparts while remaining lightweight. Its rigidity even allowed McLaren to reduce the number of carbon fiber plies over time, further trimming weight.

"McLaren were the first team to build an entire chassis with it, using techniques which have been the industry standard for three decades."

– Keith Collantine, Editor, RaceFans

Performance and Safety Results

Critics initially doubted the durability of a carbon fiber monocoque, predicting it would "disintegrate into carbon dust" on impact. However, the 1981 Italian Grand Prix at Monza silenced those doubts. During the race, John Watson crashed at the Lesmo corners at approximately 140 mph (225 km/h). The collision was catastrophic - tearing the engine and gearbox from the car and igniting a fire. Despite this, the carbon fiber monocoque remained intact, and Watson walked away with only minor injuries.

This crash demonstrated what testing had already suggested: carbon fiber's specific energy absorption ranged from 40 to 70 kJ/kg, far surpassing aluminum (20 kJ/kg) and steel (12 kJ/kg). Additionally, the MP4/1's construction involved just five main components, compared to the over 50 parts required for an aluminum chassis, resulting in a stronger and more unified survival cell. By the mid-1980s, every Formula 1 team had transitioned to carbon fiber monocoques, leaving metal chassis designs behind.

Carbon Fiber Technical Properties

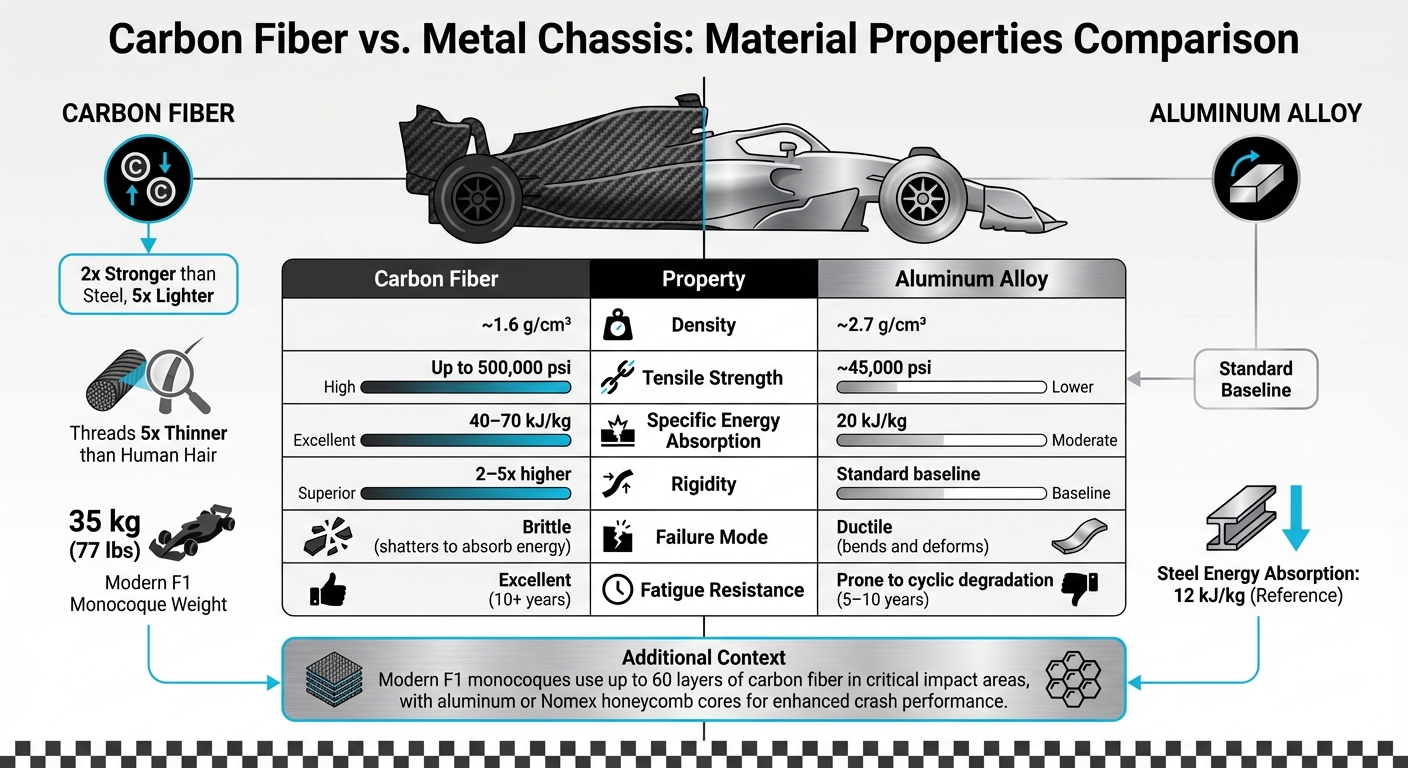

Carbon Fiber vs Metal Chassis: F1 Safety Evolution Comparison

Strength-to-Weight Ratio

Carbon fiber stands out by being twice as strong as steel while weighing five times less. When woven into mats and layered carefully, the threads - each five times thinner than a human hair - create a material with incredible rigidity. This contributes to the monocoque's ability to endure extreme forces.

A great example of this is the McLaren MP4/1. Its carbon fiber monocoque delivered over twice the stiffness of its aluminum-based competitors, all while keeping the weight comparable. Today’s F1 monocoques weigh as little as 77 lbs (35 kg) yet can withstand massive aerodynamic loads and crash forces. Engineers achieve this by laying individual carbon fiber plies in precise orientations, tailoring the structure to handle specific mechanical and aerodynamic stresses. This meticulous design ensures stability under high torsion during cornering and braking.

This strategic layering is also key to managing energy during crashes.

Energy Absorption in Crashes

Carbon fiber's Specific Energy Absorption (SEA) ranges from 40–70 kJ/kg, far exceeding steel's 12 kJ/kg and aluminum's 20 kJ/kg. Modern F1 monocoques can include up to 60 layers of carbon fiber in critical impact areas. Each layer is oriented to distribute crash forces evenly across the survival cell.

To enhance crash performance, engineers often insert aluminum or Nomex honeycomb cores between carbon fiber layers. This creates a structure that resists crushing while dissipating energy through controlled material failure. Unlike metals, which deform and bend under stress, carbon fiber retains its shape until it reaches its limit. At that point, it shatters in a way that absorbs kinetic energy, protecting the driver. Additionally, the side flanks of the survival cell are reinforced with a 6mm layer of carbon and Zylon, the same material used in bulletproof vests, to block debris penetration.

Carbon Fiber vs. Aluminum Alloy

A direct comparison highlights the advantages of carbon fiber:

| Property | Carbon Fiber | Aluminum Alloy |

|---|---|---|

| Density | ~1.6 g/cm³ | ~2.7 g/cm³ |

| Tensile Strength | Up to 500,000 psi | ~45,000 psi |

| Specific Energy Absorption | 40–70 kJ/kg | 20 kJ/kg |

| Rigidity | 2–5x higher | Standard baseline |

| Failure Mode | Brittle | Ductile |

| Fatigue Resistance | Excellent | Prone to cyclic degradation |

The key difference lies in how these materials fail. Aluminum bends and dents, offering visual warnings before breaking. Carbon fiber, on the other hand, maintains its structural integrity until it fractures completely. In F1, this brittleness is an advantage: the monocoque stays rigid under normal operation and extreme G-forces, then absorbs energy through controlled fracturing during crashes. Additionally, carbon fiber's excellent fatigue resistance allows it to remain stable for over a decade, whereas aluminum typically lasts only 5–10 years under high stress.

Major Crashes That Proved Carbon Fiber Safety

John Watson's 1981 Italian GP Crash

Back in September 1981 at Monza, critics who doubted carbon fiber's durability got an unexpected reality check. During the 1981 Italian GP, John Watson lost control of his McLaren MP4/1 at the Lesmo corners, slamming into the barriers at a speed of roughly 140 mph (225 km/h). The crash was severe enough to rip the engine and gearbox clean off the car, redirecting much of the impact energy. Yet, the carbon fiber monocoque - the car's central survival cell - remained intact, leaving Watson with only minor injuries.

"This incident went long way to removing any doubts in the minds of those unconvinced of the safety of the carbon fibre composites under strain rate loading."

This crash was a pivotal moment, proving that while external parts could break away to absorb energy, the rigid monocoque could shield the driver effectively. It marked a significant milestone in the practical application of carbon fiber safety in motorsport. And it wasn’t the last time carbon fiber would prove its worth.

Giancarlo Fisichella's 1997 Silverstone Crash

Fast forward to the 1997 British GP at Silverstone, where Giancarlo Fisichella's Jordan-Peugeot faced a terrifying high-speed collision. The onboard data revealed that the car went from 227 km/h to a complete stop in just 0.72 seconds - a force equivalent to falling from 656 feet (200 meters). Despite the sheer violence of the crash, Fisichella walked away with only a minor knee injury. How? The monocoque, composed of up to 12 layers of carbon fiber reinforced with an aluminum honeycomb core, absorbed and dispersed the impact energy. While the nose crumpled as designed to absorb the initial force, the cockpit remained intact, safeguarding the driver.

This incident not only highlighted the effectiveness of carbon fiber technology but also pushed for continued improvements in both car design and FIA crash test standards.

These two crashes, separated by 16 years, illustrate the groundbreaking impact and ongoing advancements of carbon fiber monocoque technology in Formula One. From proving its safety under extreme conditions to influencing modern crash testing protocols, carbon fiber has redefined what’s possible in driver protection.

Modern Carbon Fiber Monocoque Improvements

Formula 1 continues to push the boundaries of safety by refining materials and designs that build on the revolutionary use of carbon fiber in monocoques.

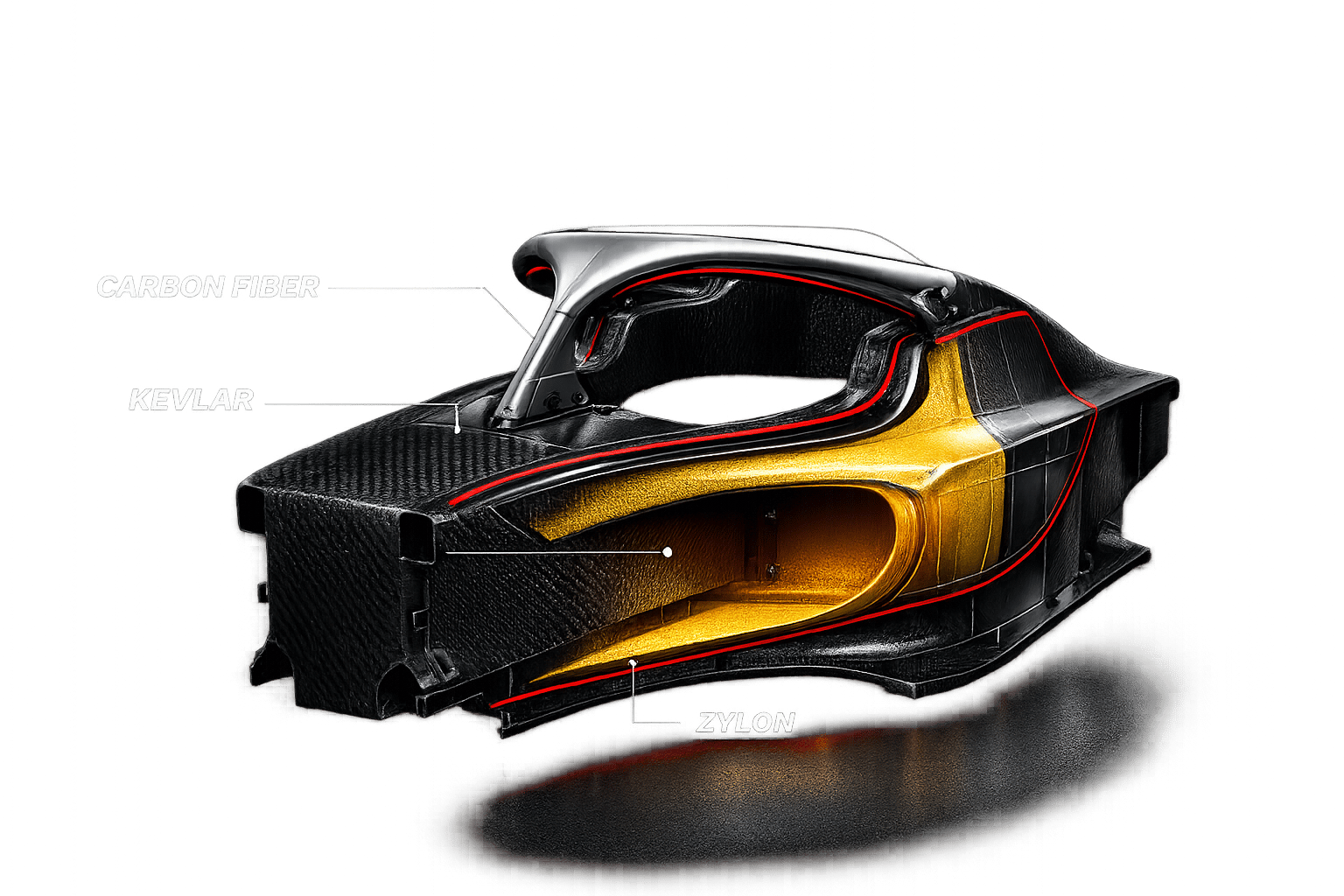

Kevlar Layer Integration

While carbon fiber offers incredible rigidity, it has a downside: brittleness. Under extreme impact, it can shatter into dangerous fragments. To address this, the FIA requires an inner layer of Kevlar in every F1 monocoque. This change was driven by a 1999 crash at Silverstone, where Michael Schumacher’s Ferrari chassis was pierced by a suspension wishbone, resulting in a leg injury. Kevlar now plays a dual role, reinforcing both the monocoque and the fuel cell behind the driver to prevent leaks or tears during high-impact crashes.

"Kevlar is a strong material and is highly resistant to penetrative forces or point dynamic loads. The mandate came after Michael Schumacher's 1999 crash at Silverstone. The front suspension wishbone had penetrated Schumacher's car and broken his leg."

– Jarrod Partridge, F1 Explained

Modern monocoques typically feature around 12 layers of carbon fiber mats, with Kevlar added specifically to prevent penetration. This design ensures that even in catastrophic crashes, the cockpit remains secure. The addition of Kevlar complements other safety measures, such as the HALO system, to create a near-impenetrable survival cell.

HALO System and Monocoque Design

The HALO device, mandatory since 2018, has transformed driver safety. Constructed from aerospace-grade titanium, this three-pronged structure is mounted directly onto the carbon fiber monocoque. While the monocoque serves as a protective shell, the HALO shields the driver’s head from flying debris, such as tires or shards, and prevents the car’s weight from crushing the driver in rollover scenarios.

The HALO is engineered to handle a vertical load of 116 kN (about 26,000 lbs), equivalent to the weight of a London double-decker bus. To support this immense load, modern monocoques incorporate a 6 mm layer of carbon fiber and Kevlar, further enhancing penetration resistance.

Real-world incidents highlight the HALO’s effectiveness. During the 2020 Bahrain Grand Prix, Romain Grosjean’s car penetrated a metal barrier and caught fire after a 67G impact. The HALO, combined with the carbon fiber monocoque, allowed him to escape the wreckage. Similarly, at the 2021 Italian Grand Prix, Max Verstappen’s car landed on Lewis Hamilton’s cockpit, with the HALO absorbing the impact and preventing serious injury.

"The final design became a three-pronged structure made from aerospace-grade titanium which can withstand a load equivalent to 116kN vertically downward or... strong enough to hold a London double decker bus."

– James Allison, Technical Director, Mercedes-AMG PETRONAS F1 Team

FIA Safety Standards and Crash Testing

In addition to material advancements, FIA safety standards ensure that every monocoque meets strict impact criteria. These regulations require monocoques to pass nearly 20 impact and load tests, simulating frontal, side, rear, and rollover collisions. The goal is to keep the "survival cell" intact while surrounding structures crumple to absorb energy.

Safety requirements have become more stringent over the years. For instance, the FIA increased the rear dynamic crash test speed from 12 m/s to 15 m/s in 2006, raising the impact energy that monocoques must endure by 56%. Today, critical areas of the monocoque feature up to 60 layers of carbon fiber, with a 6 mm layer of Zylon - known for its tensile strength - added for extra protection.

| Material | Specific Energy Absorption (SEA) | Key Safety Role |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon Fiber (CFRP) | 40–70 kJ/kg | Primary structural integrity and energy dissipation |

| Kevlar | High Penetration Resistance | Prevents cockpit penetration |

| Zylon | High Tensile Strength | Side protection and wheel tethers |

| Aluminum Honeycomb | High Rigidity | Increases torsional stiffness |

To ensure driver safety, the FIA also enforces strict dimensional rules. Drivers must be able to exit the monocoque within 5 seconds, removing only the steering wheel and seatbelts. Non-destructive testing methods like X-rays and ultrasonic scans are used to detect flaws or delamination in the monocoque.

"The monocoques used in Formula 1 are safer than they have ever been. Nonetheless, research and development in this field still continue because safety has the highest priority for the drivers."

– Brian O'Rourke, Specialist for Composite Materials, WilliamsF1 Team

These advancements, from Kevlar integration to the HALO system, reflect F1’s relentless pursuit of driver safety, building on the carbon fiber revolution that began with the McLaren MP4/1 in 1981.

Conclusion

Key Takeaways

The introduction of the carbon fiber monocoque marked a turning point in Formula 1 safety. When McLaren launched the MP4/1 in 1981, many doubted its potential. However, John Watson’s terrifying crash at Monza that year - where the engine and gearbox were torn from the car - demonstrated its life-saving capabilities. Watson walked away unscathed, silencing skeptics.

Carbon fiber’s ability to absorb energy is unmatched, with a range of 40–70 kJ/kg compared to steel’s 12 kJ/kg and aluminum’s 20 kJ/kg. This allows for a monocoque weighing just 35 kg to be both incredibly strong and lightweight. Its performance in high-speed crashes, like Giancarlo Fisichella’s 1997 accident at Silverstone or Robert Kubica’s 2007 crash, underscores its effectiveness.

Safety advancements didn’t stop there. After Michael Schumacher’s 1999 crash, the FIA mandated Kevlar inner layers to prevent cockpit penetration. The 2018 introduction of the HALO system provided critical head protection, while modern monocoques now include Zylon side panels to ensure the survival cell remains intact even as external parts crumple. These innovations have laid the groundwork for F1’s relentless pursuit of safety excellence.

Future F1 Safety Developments

Formula 1 continues to push the envelope in safety design. By February 2026, teams like Williams are rolling out chassis tailored to meet the latest safety and power unit regulations. Ferrari is experimenting with graphene for its exceptional strength, while McLaren is incorporating titanium inserts into high-stress areas to enhance durability without adding unnecessary weight. Manufacturing techniques like Resin Transfer Molding (RTM) have drastically cut production times, allowing for faster design updates. Engineers are also refining fiber orientations and layup methods to further improve energy absorption, ensuring that F1 remains at the forefront of safety innovation.

"On the infinite safety scale, it has reached a level that will be hard to surpass. Nonetheless, research and development in this field still continue because safety has the highest priority."

– Formula 1 Dictionary

FAQs

How has the carbon fiber monocoque made Formula One cars safer than metal chassis?

The carbon fiber monocoque has transformed Formula One safety by serving as a lightweight yet extremely strong protective cell. Unlike traditional metal chassis, its design is engineered to absorb and distribute crash energy more efficiently, reducing the force that reaches the driver.

This advancement significantly improves driver protection in high-speed crashes and lowers the chances of structural failure, establishing it as a key element in today's F1 safety measures.

How do Kevlar and Zylon improve the safety of F1 monocoques?

Kevlar and Zylon play a crucial role in boosting driver safety within F1 monocoques. These high-performance fibers are engineered to deliver outstanding strength and energy absorption, offering critical protection during high-impact crashes.

Kevlar stands out for its toughness and ability to resist punctures, while Zylon excels in tensile strength and heat resistance. When combined, these materials strengthen the carbon fiber structure of the monocoque, ensuring it holds up against extreme forces and remains intact during pivotal moments.

How does the HALO system work with the carbon fiber monocoque to protect F1 drivers?

Driver safety in Formula One relies heavily on two key components: the HALO system and the carbon fiber monocoque. These two elements work together to provide a robust defense against the dangers of high-speed racing.

The monocoque, often referred to as the driver’s safety cell, is crafted from carbon fiber. This material is both lightweight and incredibly strong, making it ideal for absorbing and redistributing the forces generated during a crash. Its primary role is to shield the driver by managing the overall energy from an impact.

Above the cockpit sits the HALO, a titanium safety bar designed to protect the driver’s head. This structure acts as a barrier, deflecting debris and absorbing impacts, especially during severe collisions. It’s a crucial safeguard against objects entering the cockpit area.

Together, these systems create a comprehensive safety solution. The monocoque manages the crash's energy, while the HALO provides critical head protection. This combination has significantly lowered the risk of life-threatening injuries, enabling drivers to survive high-speed crashes with minimal harm. It's a testament to Formula One's relentless dedication to improving safety standards.