Colin Chapman: F1's Maverick Engineer

How 'simplify, then add lightness' transformed F1 — monocoque chassis, stressed-member engines and ground-effect aerodynamics that still shape modern car design.

Colin Chapman transformed Formula One with his bold engineering ideas and business foresight. Founder of Team Lotus, he introduced lightweight design, monocoque chassis, ground-effect aerodynamics, and the stressed-member engine. His mantra, "Simplify, then add lightness," reshaped car performance by prioritizing weight reduction over raw engine power. Chapman also pioneered commercial sponsorship in F1, turning race cars into branding platforms. His innovations earned Lotus 7 Constructors' and 6 Drivers' Championships, leaving a legacy that still influences F1 car design today.

Chapman's Core Engineering Philosophy

Where 'Simplify, Then Add Lightness' Came From

Colin Chapman's well-known mantra, "Simplify, then add lightness", was deeply rooted in his background as a structural engineer and his time in the Royal Air Force. His experiences shaped his approach to car design, where he applied lessons from aircraft construction - where every ounce counts - to the world of racing. This philosophy aligns with Antoine de Saint-Exupéry's famous idea: "Perfection is reached not when there is nothing more to add, but when there is nothing left to take away".

Chapman's method was straightforward: strip away anything unnecessary and refine what remained to its essential core. This wasn’t about cutting corners; it was about pushing engineering boundaries. He believed in designing parts to operate at the absolute edge of their strength. If a component didn’t fail just after completing a race, Chapman deemed it overbuilt and unnecessarily heavy. This mindset became known as the "break and fix" approach. F1 driver Innes Ireland captured the essence of this philosophy:

"Colin's idea of a grand prix car was it should win the race and, as it crossed the finishing line, it should collapse in a heap of bits. If it didn't do that, it was built too strongly."

Chapman himself put it even more directly:

"Any car which holds together for a whole race is too heavy."

This radical approach not only revolutionized car design but also shifted how performance was measured on the track.

How Lightweight Design Changed F1 Performance

Chapman's commitment to reducing weight fundamentally transformed Formula 1 performance, impacting every aspect of a car's capabilities. While many of his competitors focused on building bigger and more powerful engines, Chapman understood a key principle: adding power might improve straight-line speed, but reducing weight enhanced everything - from acceleration to handling and braking.

The Lotus 18, Chapman's first mid-engined Grand Prix winner, exemplified this philosophy. It weighed just 970 pounds and stood only 28 inches tall. Traditional designers often relied on heavy chrome-moly tubing with large safety margins, but Chapman took a different route, using brazed mild steel welds to shave off unnecessary weight. This approach initially shocked American inspectors at Indianapolis, but the results spoke for themselves. Under Chapman's leadership, Lotus secured seven F1 Constructors' titles and six Drivers' championships.

One of Chapman's most groundbreaking innovations was the Lotus 25, featuring a monocoque chassis. This design was three times stiffer and significantly lighter than its predecessor. In 1963, Jim Clark dominated the season, winning seven out of ten races and securing both the Drivers' and Constructors' championships. Chapman's work proved that smart weight reduction could outperform brute horsepower, forever changing the sport.

1968: The Man Who Made LOTUS Racing - Colin Chapman | Millionaire | Classic Motorsport | BBC Archive

Chapman's Major Technical Contributions

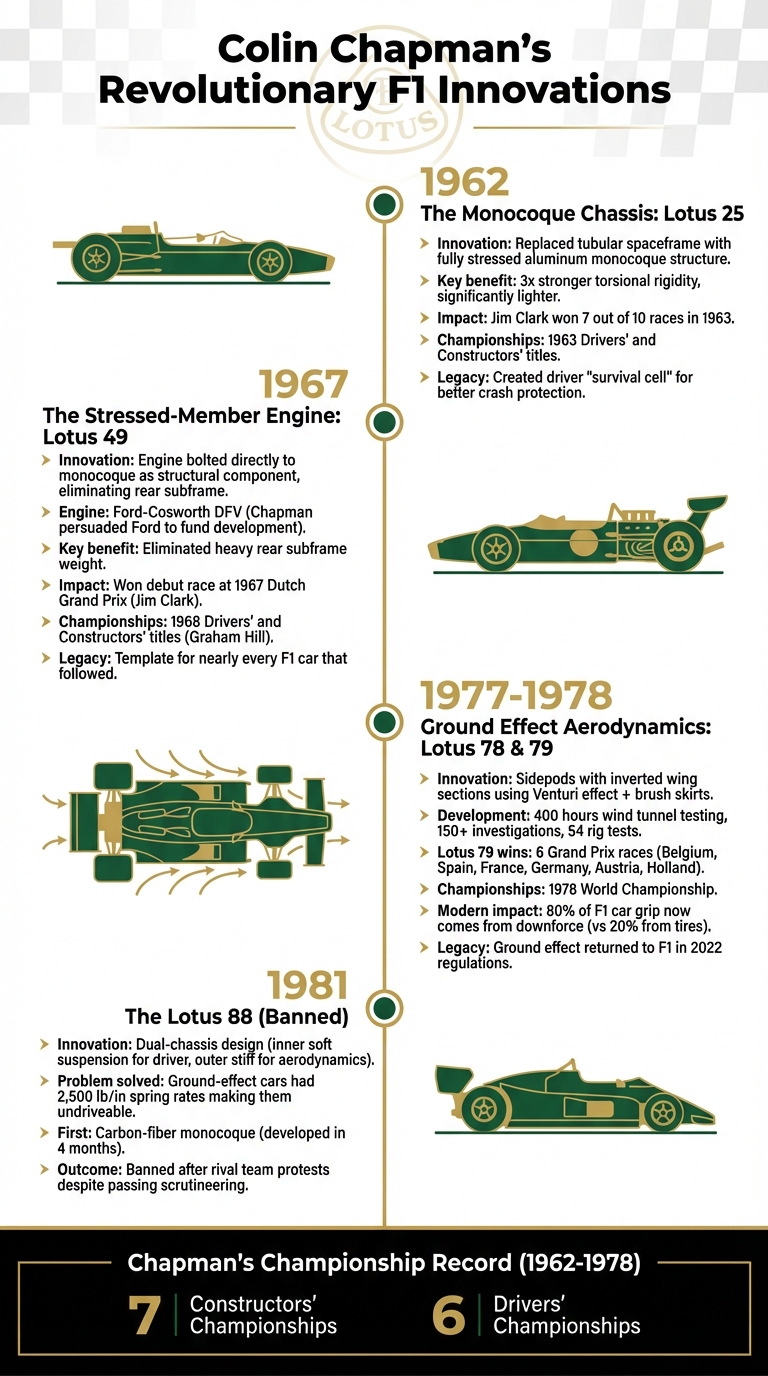

Colin Chapman's Revolutionary F1 Innovations Timeline (1962-1981)

Colin Chapman revolutionized Formula One car design, introducing three groundbreaking innovations that shaped the foundation of modern racing cars: the monocoque chassis, ground effect aerodynamics, and the stressed-member engine. Each of these ideas not only reduced weight but also boosted performance, aligning with Chapman’s belief that clever engineering could outclass sheer power. Let’s dive into how each of these advancements transformed F1 design.

The Monocoque Chassis: Lotus 25

In 1962, Chapman introduced the Lotus 25, a car that replaced the traditional tubular spaceframe with a fully stressed monocoque structure. Instead of relying on an internal frame, the Lotus 25 used an aluminum skin as the load-bearing chassis. This innovation eliminated the bulky frame entirely, resulting in a car that was slimmer, lower, and much lighter than its competitors on the grid.

The monocoque design wasn’t just lighter - it was also three times stronger in torsional rigidity compared to its predecessor. Chapman took it a step further by introducing a reclined driving position, which reduced the car’s frontal area and aerodynamic drag - an approach that’s now a standard feature in modern F1 cars. Another key advantage was the creation of a "survival cell" for the driver, offering better crash protection than the fragile tube-frame designs of the time.

Jim Clark’s performance in the 1963 season proved just how effective the Lotus 25 was. Clark won seven out of ten races, securing both the Drivers’ and Constructors’ World Championships. The car’s dominance forced competitors to adopt monocoque construction. While today’s F1 cars use carbon fiber instead of aluminum, the core principle of Chapman’s design remains unchanged.

Aerodynamics and Ground Effect: Lotus 78 and 79

Chapman’s next major breakthrough came in 1977 with the Lotus 78, often referred to as the "wing car." This innovation introduced sidepods with inverted wing sections underneath, using the Venturi effect to create massive downforce. The addition of brush skirts to seal the low-pressure area beneath the car amplified the effect, effectively "gluing" the car to the track.

The development process was meticulous, involving 400 hours of wind tunnel testing at Imperial College, London, and over 150 individual investigations and 54 rig tests. Mario Andretti famously described the sensation of driving the Lotus 78 as feeling "painted to the road". The technology reached its peak with the Lotus 79 in 1978, which won six Grand Prix races (Belgium, Spain, France, Germany, Austria, and Holland) and secured the World Championship.

This shift in design philosophy moved F1 from relying on bolt-on wings to managing airflow around the entire car body. Chapman’s approach directly challenged Enzo Ferrari’s assertion that "aerodynamics was for people who didn’t know how to build a powerful engine". Today, it’s estimated that 80% of an F1 car’s grip comes from downforce, with only 20% from the tires - a testament to the lasting impact of Chapman’s work.

The Stressed-Member Engine: Lotus 49 and Cosworth DFV

In 1967, Chapman introduced one of his most elegant engineering solutions: the stressed-member engine. The Lotus 49 featured a truncated chassis that ended just behind the driver’s shoulders, with the Ford-Cosworth DFV engine bolted directly to the monocoque. The rear suspension was then attached to the engine and gearbox, eliminating the need for a heavy rear subframe.

Chapman’s ability to persuade Ford to fund Cosworth’s development of the 3-liter DFV engine was pivotal to this design. As Chapman explained:

"It is a much more elegant structural proposition, you are able to react the loads between the transmission and the engine directly in one package."

The Lotus 49 made an immediate impact, winning its debut race at the 1967 Dutch Grand Prix with Jim Clark at the wheel. Graham Hill later used the car to win the 1968 Drivers’ and Constructors’ Championships. The stressed-member engine design became a template for nearly every Formula One car that followed, while the DFV engine itself dominated the sport for over a decade. This integration of engine and chassis set a structural standard that continues to influence F1 engineering today.

Chapman's Unconventional Solutions to Engineering Problems

Colin Chapman's genius wasn't just about creating groundbreaking designs - it was also about finding clever ways to tackle engineering problems. He had a knack for interpreting Formula One regulations in ways that gave Team Lotus a competitive edge, often operating in the sport's regulatory gray areas. While this approach earned him praise for his ingenuity, it also sparked controversy for pushing the limits of what was allowed. One of the most striking examples of this mindset was the creation of the Lotus 88.

The Lotus 88 and Its Dual-Chassis Design

In 1981, Chapman introduced the Lotus 88, a car that tackled a major challenge in ground-effect design. Ground-effect cars needed extremely stiff spring rates - up to 2,500 lb/in - to maintain the consistent ride height required for aerodynamic efficiency. This stiffness made the cars almost undriveable; drivers struggled to even keep their feet on the pedals. Chapman's bold solution? A car with two separate chassis.

The inner chassis, or "tub", carried the driver and engine and featured a softer suspension for better control and comfort. Meanwhile, the outer chassis supported the aerodynamic components, including the bodywork, undertray, and rear wing. At high speeds, this outer chassis compressed against hard stops to enhance downforce. It was a daring interpretation of the rules. As Peter Wright, Team Lotus's Technical Manager, put it:

"The rules banned cars with no suspension, but they hadn't thought of two suspensions".

Chapman even exploited a linguistic loophole, pointing out that the plural of "chassis" is still "chassis", and argued that the rules didn't explicitly forbid a car from having more than one.

The Lotus 88 also introduced the first carbon-fiber monocoque, developed in just four months. Despite its technical brilliance and passing initial scrutineering, the car faced protests from rival teams. Ultimately, it was banned, leaving Chapman disillusioned with what he saw as the growing influence of politics over technical progress in Formula One.

Creative Rule Interpretation and Problem-Solving

The Lotus 88 was far from Chapman's first brush with bending the rules. Early in his career, he modified an Austin 7 cylinder head to create an 8-port engine from a 6-port casting, dominating the competition until a rule change specifically outlawed the modification. Later, when sliding skirts used for ground-effect aerodynamics were challenged as "movable aerodynamic devices", Chapman managed to persuade the FIA to allow them temporarily.

Tony Southgate, a former designer at Lotus, summed up Chapman's approach perfectly:

"If it was illegal, Colin would go for it. 'Let's get the FIA to change the rules somehow.' He leaned on the FIA, don't know how he managed it, and talked them into accepting it".

Chapman's career was defined by this relentless drive to think outside the box and challenge the status quo. Even when his methods stirred controversy, they often delivered results, cementing his reputation as one of motorsport's most daring innovators.

Chapman's Lasting Influence on Formula One

Chapman's Championships and Most Important Cars

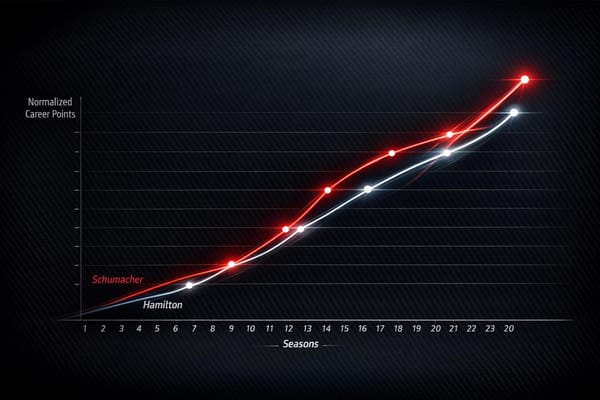

Between 1962 and 1978, Colin Chapman guided Lotus to an impressive 7 Constructors' and 6 Drivers' Championships. But his influence extended far beyond trophies - his cars reshaped Formula One design. The monocoque Lotus 25, the stressed-member Lotus 49, and the groundbreaking ground-effect Lotus 79 each pushed the boundaries of engineering in the sport. Chapman didn’t just transform F1; he also left his mark on American motorsport. In 1965, Jim Clark drove the mid-engined Lotus 38 to victory at the Indianapolis 500, revolutionizing the race with a design that set new standards. These achievements laid the foundation for innovations that still define modern F1 cars.

Chapman's Ideas in Modern F1 Design

Chapman’s groundbreaking concepts continue to shape Formula One today. The monocoque chassis, first introduced by Lotus, remains the backbone of every F1 car - though now constructed from carbon fiber instead of aluminum. Similarly, the use of the engine and gearbox as structural components, a hallmark of the Lotus 49, is now a standard design feature.

His influence doesn’t stop there. The sidepod configurations he introduced remain integral to modern car aerodynamics. Ground-effect technology, which Chapman developed with the Lotus 78 and 79, made a comeback in 2022 as the primary method for generating downforce under the updated technical regulations. Even the reclined driver position, first seen in the Lotus 25 to lower the car’s center of gravity, has become the norm in single-seater racing.

Chapman’s mantra, "simplify, then add lightness", still guides engineering decisions in Formula One. Teams today go to great lengths to reduce weight, utilizing advanced composites and cutting-edge materials - an approach that echoes his philosophy from decades ago. As Chapman famously said:

"Adding power makes you faster on the straights. Subtracting weight makes you faster everywhere".

This principle is just as vital to F1 success now as it was during his era.

Conclusion: The Engineer Who Transformed Formula One

Colin Chapman wasn’t just an engineer who built fast cars - he was the mastermind who reshaped the way racing cars are designed. His groundbreaking ideas, like the monocoque chassis, the stressed-member engine, and ground-effect aerodynamics, laid the foundation for the carbon fiber, load-bearing designs we see on the grid today.

His mantra - "Simplify, then add lightness" - is still a cornerstone of Formula One engineering. Teams continue to push boundaries, finding innovative ways to reduce weight and gain an edge. Chapman's relentless drive to strip away the unnecessary and focus on efficiency remains at the heart of modern F1 design philosophy.

Beyond his technical genius, his success on the track speaks volumes. With multiple championships to his name, Chapman proved that his bold ideas weren’t just theoretical - they delivered results. From repositioning radiators to adopting a reclined driver position and pioneering ground-effect aerodynamics, he consistently challenged the norm. This fearless approach to innovation has become a defining characteristic of Formula One and ensures his influence is felt even decades later.

Chapman passed away suddenly on December 16, 1982, at the age of 54. Yet his legacy lives on in every corner of the sport. His famous words still resonate:

"Adding power makes you faster on the straights. Subtracting weight makes you faster everywhere."

Every Formula One car on today’s grid is a tribute to his vision, a reminder of an engineer who forever changed the game.

FAQs

How did Colin Chapman's 'simplify, then add lightness' philosophy shape modern F1 car design?

Colin Chapman's mantra, "simplify, then add lightness," transformed Formula 1 engineering and continues to shape modern car design. By focusing on simplicity and reducing weight, Chapman demonstrated that lighter cars excel across the board - whether it's sharper cornering or quicker acceleration.

His groundbreaking ideas left a lasting impact in three major ways. First, the Lotus 25 introduced the all-monocoque chassis, replacing the bulkier space-frame designs and setting the stage for today's ultra-light carbon-fiber monocoques. Second, the Lotus 49 revolutionized design by using the engine as a stressed member, cutting unnecessary structural weight - a concept still at the heart of modern F1 cars. Lastly, his minimalist mindset led to aerodynamic innovations, such as the ground-effect Lotus 79, proving that sleek, lightweight designs could generate incredible downforce without adding drag.

Chapman's philosophy remains a guiding force in F1, influencing how teams fine-tune the balance between speed, efficiency, and weight to stay ahead in the competition.

What groundbreaking innovations did Colin Chapman bring to Formula One design?

Colin Chapman left an indelible mark on Formula One, reshaping race car engineering with ideas that changed the game forever. His guiding principle, "simplify, then add lightness," led to the groundbreaking development of the first monocoque chassis in the Lotus 25. By ditching the traditional, heavier space-frame design in favor of a single aluminum tub, Chapman not only slashed weight but also boosted structural rigidity. This innovation became a new benchmark in car design.

Another of Chapman’s transformative ideas was using the engine as a stressed member of the chassis, a concept first applied in the Lotus 49. By making the engine part of the car’s structural framework, he eliminated the need for a separate sub-frame. The result? A lighter, stiffer car that performed better on the track. Aerodynamics was another area where Chapman broke new ground. The Lotus 72 introduced a wedge-shaped nose and side-mounted radiators, which reduced drag while increasing downforce. Later, the Lotus 79 took things further, becoming the first car to fully exploit ground-effect aerodynamics. This innovation generated incredible grip, revolutionizing cornering performance.

Chapman’s contributions - lightweight design, stressed-member chassis integration, and advanced aerodynamics - remain integral to modern Formula One engineering, solidifying his place as one of the sport’s most brilliant innovators.

Why was the Lotus 88 banned despite its groundbreaking dual-chassis design?

The Lotus 88 faced a ban due to its cutting-edge dual-chassis design. This setup included an outer aerodynamic shell that operated independently of the inner chassis, where the driver sat. The FIA, responding to objections from rival teams, determined that this design violated Formula One rules regarding movable aerodynamic devices and the required 6 cm ride-height regulation, ultimately declaring the car illegal.

Though the Lotus 88 showcased groundbreaking engineering, its unconventional design was perceived as offering an unfair edge, leading to its disqualification before it had the chance to prove itself on the track.