Driver Salary Cap Debate: Big vs. Small Teams

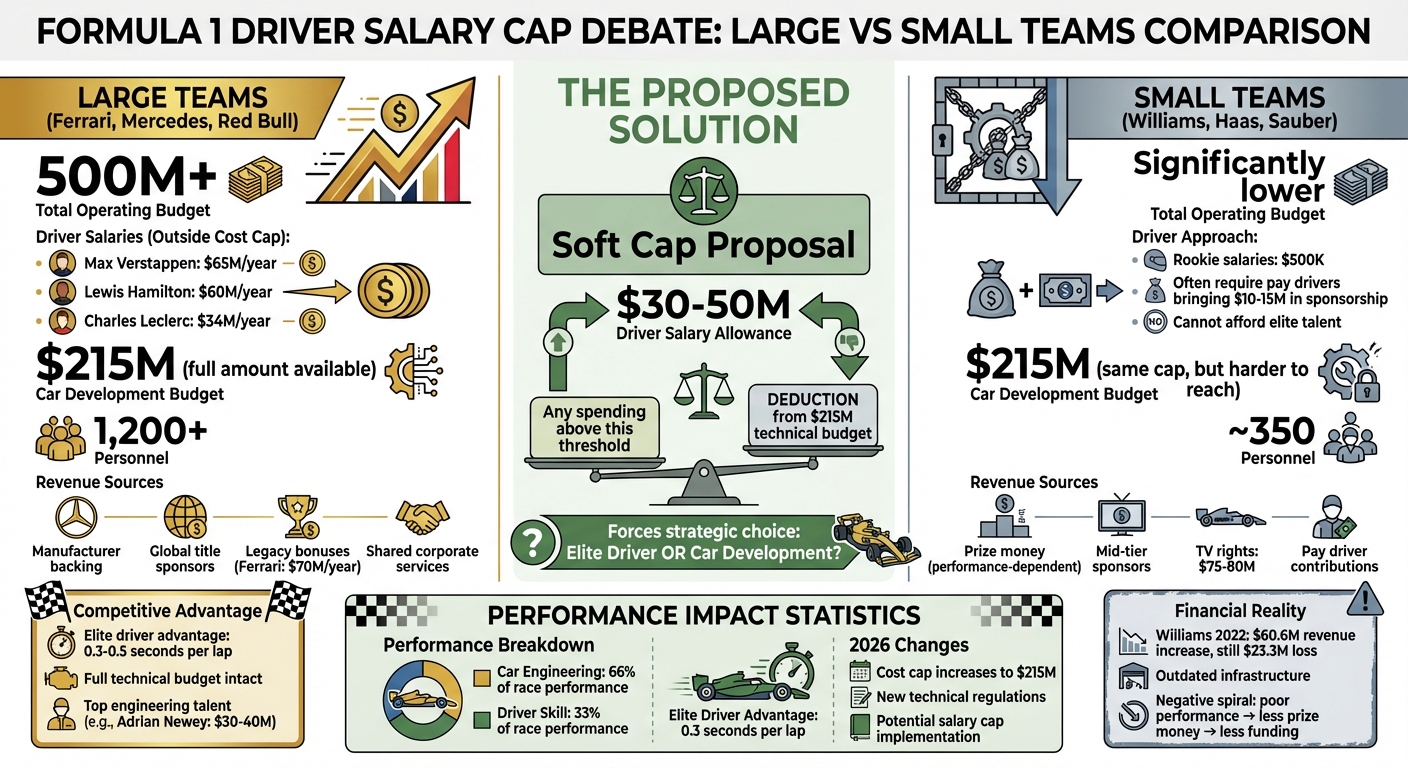

Explores including driver salaries in F1's $215M cost cap, a proposed $30–$50M allowance, and the impact on competitive balance between large and small teams.

Formula 1 is facing a hot debate: Should driver salaries be included in the $215 million cost cap? Currently, salaries for drivers and top team personnel are exempt, giving wealthier teams like Ferrari, Red Bull, and Mercedes a big advantage. Smaller teams argue this creates an uneven playing field, as elite drivers can bring up to a 0.3-second per lap advantage.

Key Points:

- Current Rules: Driver salaries are not part of the cost cap, which applies to technical expenses like car development.

- Proposed Solution: A "soft cap" of $30–$50 million for driver salaries. Exceeding this would reduce a team's car development budget.

- Big Teams' Argument: Drivers are global icons who generate revenue and deserve high pay. Long-term contracts, like Verstappen's $55M/year deal through 2028, complicate changes.

- Small Teams' Argument: Including salaries in the cap would level the field and force teams to balance spending between drivers and car upgrades.

- Financial Gap: Top teams operate with budgets over $500M, while smaller teams like Haas often rely on pay drivers to stay afloat.

With new technical regulations and a higher cost cap in 2026, this debate could reshape the sport. Will F1 prioritize competitive balance or allow big teams to keep their edge?

F1 Cost Cap Debate: Large vs Small Teams Financial Comparison

Formula 1's Financial Framework in 2026

The $215 Million Cost Cap and Driver Salary Exemption

In 2026, Formula 1's cost cap will rise to $215 million per team, up from $145 million in 2021. This adjustment accounts for inflation and applies to performance-related expenses like aerodynamics, chassis development, wind tunnel usage, and factory operations.

However, not everything falls under this cap. Driver salaries, along with fees for the top three personnel, remain exempt. Marketing expenses and heritage activities are also excluded. Existing contracts and legal obligations make retroactive changes impossible. For example, Max Verstappen's contract, worth about $55 million annually, runs through 2028, while Lewis Hamilton earns around $50 million per year. Both agreements were signed before salary cap discussions gained momentum.

"What we don't want to see is that Formula 1 becomes an accounting World Championship rather than a technical or sporting one."

– Christian Horner, Team Principal, Red Bull

To address concerns, a "soft cap" on driver salaries has been proposed, ranging between $30 million and $50 million. Under this system, any spending beyond the cap would be deducted from the team's $215 million technical budget. This approach forces teams to weigh the benefits of hiring an elite driver against investing in car development.

"I'm in favour of adding that underneath a global cap so that the teams can trade off driver skill with updates, because ultimately both things bring performance on-track."

– Otmar Szafnauer, Team Principal, Alpine

This debate highlights the challenge of balancing driver salaries with technical investment. Yet, these exemptions also magnify financial disparities between teams, making revenue differences a key factor in Formula 1's competitive landscape.

Revenue Differences Between Large and Small Teams

Even with a cap on technical spending, the financial playing field remains uneven due to significant revenue disparities. Ferrari, for instance, receives around $70 million annually in legacy bonuses thanks to its historic status in the sport. Top teams like Mercedes and Ferrari operate with budgets exceeding $500 million, while smaller teams like Haas or Williams often struggle to compete financially. These smaller teams sometimes rely on drivers who bring in sponsorships worth $10 million to $15 million just to secure a seat.

Here's a snapshot of how revenue differences impact team operations:

| Team Category | Primary Revenue Sources | Driver Spending Capability |

|---|---|---|

| Large Teams (Ferrari, Mercedes, Red Bull) | Manufacturer backing, global title sponsors, legacy bonuses, shared corporate services | Can spend $40M–$55M on drivers without affecting the $215M car development budget |

| Small Teams (Williams, Haas, Sauber) | Prize money, mid-tier sponsors, pay driver contributions | Often need drivers to bring sponsorship money rather than command high salaries |

Large teams can leverage their financial advantage to secure elite drivers and top-tier personnel, while smaller teams are often forced to focus on survival. For example, Williams saw a $57 million revenue boost in 2022 due to the sport's growth, but outdated infrastructure continues to hinder their competitiveness. This creates a "negative spiral" where poor performance limits prize money, which in turn restricts funding for much-needed upgrades.

Statistical analysis reveals that car engineering accounts for about 66% of race performance, while driver skill contributes roughly 33%. A top driver can provide an estimated 0.3-second advantage per lap, a margin that wealthier teams can afford to "buy" outside the cost cap. Meanwhile, engineering improvements must come from within the $215 million limit. These financial inequalities underline the ongoing debate over driver salary caps, as revenue gaps continue to fuel competitive imbalances in the sport.

Large Teams: Using Financial Resources to Secure Top Drivers

Elite Driver Salaries at Top Teams

The gap between rookie and elite driver salaries in Formula 1 highlights the sport's growing financial divide. In 2025, Max Verstappen earns an impressive $65 million annually at Red Bull, while Lewis Hamilton's switch to Ferrari secured him $60 million per year. Charles Leclerc follows with $34 million at Ferrari, while mid-tier drivers like Lando Norris and Fernando Alonso earn around $20 million each. On the other hand, rookie drivers often start with salaries as low as $500,000. These figures emphasize the financial muscle required to attract top-tier talent, which in turn delivers commercial benefits. For example, Hamilton's move to Ferrari not only strengthened their driver lineup but also caused their share price to rise by 6%, adding $6.12 billion in market value.

But the spending doesn't stop with drivers. Teams like Red Bull and Ferrari also invest heavily in top engineering talent. The cost cap rules allow exemptions for the highest-paid personnel, enabling teams to hire experts like Adrian Newey, whose salary reportedly ranges between $30 million and $40 million. This strategic use of financial resources creates a talent monopoly, making it nearly impossible for smaller teams to compete on the same level. The result is a dual advantage: securing the best drivers while maintaining significant development budgets.

How Financial Flexibility Creates Competitive Advantages

Big-budget teams use their financial freedom to outpace competitors, especially in the ongoing debate over salary caps. By exempting driver salaries from the $215 million technical budget, these teams can allocate the full amount toward car development, all while paying premium rates to secure elite drivers. Smaller teams, however, are often forced to choose between hiring affordable drivers or risking a competitive disadvantage.

The advantage of financial flexibility extends beyond salaries. Manufacturer backing and lucrative sponsorship deals provide top teams with additional resources. Between 2010 and 2018, Ferrari generated $17.8 billion in sponsorship revenue, ensuring they could fund driver contracts without affecting their development budgets. Similarly, Daimler AG contributed $80 million to Mercedes in 2019 to support their championship efforts. Beyond direct funding, large teams benefit from shared resources like advanced data centers, factory facilities, and marketing budgets, which smaller teams must pay for themselves.

"I'm in favour of adding that underneath a global cap so that the teams can trade off driver skill with updates, because ultimately both bring performance on-track."

– Otmar Szafnauer, Former Team Principal, Alpine

The performance benefits of elite drivers are measurable. Experts estimate that top drivers can deliver up to 0.3 seconds per lap advantage, a margin that wealthier teams can afford without cutting into their engineering investments. Meanwhile, smaller teams, operating with just 350 personnel compared to the 1,200 or more employed by top teams, face an uphill battle to achieve similar results under the constraints of a capped budget.

Small Teams: Financial Limits and Competitive Challenges

Budget Constraints and Driver Recruitment

Smaller teams in Formula 1 face a tough uphill battle. While they struggle to stay within the $215M car development cap, they’re also up against competitors who can afford to spend $40M–$50M annually on top-tier drivers. This financial pressure forces teams like Williams, Haas, and Alpine to rely on "pay drivers" - drivers who bring sponsorship money to help cover team expenses.

Even with $75M–$80M in revenue from TV rights, these teams still fall short compared to powerhouses like Ferrari, Red Bull, and Mercedes. Take Williams Racing in 2022 as an example: despite a revenue boost of roughly $60.6M (converted from £46.6M), they still reported losses of about $23.3M (converted from £17.9M) due to the immense cost of staying competitive. Poor on-track performance worsens the situation, reducing sponsorship opportunities and leaving less money for both car development and driver recruitment. This creates a vicious cycle where limited budgets lead to weaker performance, which in turn limits future funding.

The Growing Performance Gap

The financial imbalance becomes even more obvious when looking at performance on the track. Driver salaries are exempt from the cost cap, which has only widened the gap instead of leveling the field. Top-tier drivers can deliver a 0.3 to 0.5-second per lap advantage - a margin that often separates point-scoring finishes from being stuck at the back. Big-budget teams can afford this competitive edge without compromising their $215M development budget, while smaller teams are left choosing between financial stability and hiring a more competitive driver.

This growing disparity has led smaller teams to push for reforms. For example, Alfa Romeo’s team principal, Frederic Vasseur, has suggested a system where any driver salary exceeding $30M would count against the team’s main budget cap. The idea is simple: by including all performance-related expenses under a single cap, teams could decide whether to focus on engineering improvements or invest in driver talent, rather than being outspent on both fronts. This debate over driver salaries and cost caps is central to ensuring a more balanced and competitive Formula 1 landscape.

How F1 Teams ACTUALLY Spend $350M a Year (ft. Guenther Steiner)

Should Driver Salaries Be Included in the Cost Cap?

The discussion about financial fairness in Formula 1 naturally leads to a hotly debated question: should driver salaries count toward the $215 million cost cap?

The Case for Including Driver Salaries

Smaller teams argue that driver salaries are just as critical to on-track performance as technical upgrades. By excluding these salaries from the cost cap, wealthier teams gain a significant edge, allowing them to attract top-tier drivers while still investing heavily in car development. Otmar Szafnauer, Alpine's Team Principal, explained this perspective:

"I'm in favour of adding that underneath a global cap so that the teams can trade off driver skill with updates, because ultimately both things bring performance on-track."

- Otmar Szafnauer, Alpine

One idea gaining traction is the introduction of a "soft cap" or "allowance." Under this system, teams could spend up to $30 million on driver salaries without penalty, but anything beyond that would be deducted from their car development budget. This approach forces teams to make strategic decisions: spend big on a superstar driver - whose salary could range from $50 million to $65 million - or allocate those funds to improve the car. McLaren’s Team Principal Andreas Seidl emphasized this trade-off:

"Our position is that everything which is performance relevant should be considered to be in a kind of cap or allowances."

This proposal aims to address the financial imbalance between teams. While smaller teams struggle to keep up with driver costs, wealthier teams can afford both top drivers and cutting-edge technical upgrades. Guenther Steiner, Haas's Team Principal, summed up the goal:

"The goal will be to force teams to balance spending on drivers and spending on developing the car."

Williams' Acting Team Principal Simon Roberts echoed this sentiment, suggesting that such measures could reduce disparities over time:

"It gives everybody the flexibility they need. And I expect over the long term it will even up some of the disparity that currently exists in the market."

However, while smaller teams see this as a way to level the playing field, larger teams argue that implementing such changes would be legally and logistically challenging.

The Case Against Including Driver Salaries

Top teams, on the other hand, contend that drivers deserve to remain outside the cost cap due to their unique status in the sport. Long-term contracts, such as Max Verstappen’s deal through 2028 or Charles Leclerc’s multi-year agreement, complicate the idea of retroactively applying a cap. Mercedes' Team Principal Toto Wolff defended the high salaries:

"They are tremendous superstars. They deserve to be among the top earners in the sport."

Unlike athletes in other sports leagues, such as the NBA or NFL, Formula 1 drivers rely heavily on team salaries rather than endorsements. Critics argue that capping their pay would unfairly penalize the sport's biggest talents.

Another concern is the potential impact on junior driver programs. Many young racers in Formula 3 or Formula 2 rely on investor backing to cover costs that can reach €1 million annually. These investors often expect a return on their investment when the driver reaches Formula 1. A salary cap could reduce these returns, discouraging investment in emerging talent. Max Verstappen highlighted this issue:

"It's going to limit that [junior categories] a lot because they will never get their return in money if you get a cap."

Christian Horner, Red Bull's Team Principal, warned against turning Formula 1 into an overly budget-focused sport:

"What we don't want to see is that Formula 1 becomes an accounting World Championship rather than a technical or sporting one."

Additionally, top drivers like Lewis Hamilton and Max Verstappen contribute significantly to their teams' revenue through championship points, podium finishes, and brand recognition. Ferrari's former Team Principal Mattia Binotto pointed out that a salary cap would primarily affect just a few teams:

"The salary cap for drivers will affect mainly only three, four maximum, teams, not more than that."

Team Strategies and Future Outlook

Performance-Based Contract Structures

Teams are rethinking their contract strategies as they aim to balance spending between driver salaries and technical development. A growing trend is the shift toward performance-based driver contracts, which link pay more closely to results. This approach helps teams avoid committing to massive fixed salaries that could otherwise limit resources for advancing car performance.

One proposed model suggests a salary allowance of $30–$50 million for a driver lineup, with any excess being deducted from the car development budget. This forces teams to carefully weigh their spending priorities. For instance, larger teams like Ferrari and Red Bull, whose top drivers earn around $50 million annually, currently operate well beyond this proposed threshold. These teams rely on stable base salaries due to long-term contracts. On the other hand, smaller teams, such as Williams, have successfully secured capital expenditure exemptions - about $20 million - to modernize outdated facilities.

How 2026 Technical Regulations May Affect the Debate

This shift in contract strategies coincides with significant changes in technical and financial regulations for the 2026 season. The cost cap will rise to $215 million, marking a 30.3% increase from 2024 levels. This adjustment accounts for the high R&D expenses tied to new aerodynamic designs and hybrid power units. However, it also integrates previously exempt costs like marketing and human resources, leaving teams with less room for discretionary spending.

The challenge for teams is clear: they must decide whether to prioritize cutting-edge technology or invest heavily in elite driver talent. This trade-off has been at the heart of ongoing debates. As Alpine Team Principal Otmar Szafnauer explained:

"I'm in favour of adding that underneath a global cap so that the teams can trade off driver skill with updates, because ultimately both things bring performance on-track."

Haas Team Principal Guenther Steiner echoed this sentiment, stating:

"At some stage there will be a crossover point coming that if you invest in a driver you cannot invest in the car."

The new regulations could encourage teams to adopt an "A-list plus affordable" driver pairing strategy - combining a high-profile star with a more cost-effective second driver. This would free up funds for the expensive new engines and active aerodynamics required under the 2026 rules. Additionally, new geographical compensation mechanisms, which offer budget flexibility to teams in high-wage countries like Switzerland, may reshape the competitive dynamics of driver recruitment.

Conclusion: Finding the Balance Between Competition and Financial Stability

The ongoing debate over salary caps in Formula 1 highlights a central conflict within the sport: large teams aim to maintain their edge by freely spending on top-tier talent, while smaller teams push for measures that create a fairer playing field. Formula 1 has grown into a massive $14 billion enterprise from its earlier $4–$6 billion valuation. Yet, this financial growth has done little to ease the competitive divide - it has, in fact, made it more pronounced.

A potential solution lies in the proposed salary allowance model, which allocates $30–$50 million for driver salaries while deducting any excess from the technical budget. This forces teams to make strategic choices, as Alpine's Otmar Szafnauer pointed out: they’ll need to decide between investing in driver talent or focusing on car development. However, this plan isn’t without its challenges. Contracts like Max Verstappen’s, which extend through 2028, complicate implementation. Additionally, there are concerns that such limits might discourage investment in grooming young drivers.

The broader implications of this debate stretch beyond just competition. Formula 1’s long-term viability depends on finding the right financial framework. For example, the "sloped" capital expenditure exemptions granted to teams like Williams - roughly $20 million for upgrading facilities - show that well-targeted financial rules can help address disparities. A similar approach to driver salaries could prevent the sport from evolving into what Christian Horner cautioned against:

"What we don't want to see is that Formula 1 becomes an accounting World Championship rather than a technical or sporting one."

With the 2026 season introducing a $215 million cost cap and new technical regulations, there’s a prime opportunity to implement changes that balance spending on technology with investment in driver talent. Drawing inspiration from American sports, where capped base salaries coexist with independent endorsement deals, Formula 1 could protect team budgets without limiting drivers’ earning potential.

At its heart, this discussion is about more than just budgets - it’s about the soul of the sport. Formula 1 must ensure financial stability without sacrificing the competitive thrill that defines it. Smaller teams need a shot at success, but not at the expense of the meritocracy that rewards engineering brilliance and driver skill. Whether the salary allowance system strikes this balance will not only shape race outcomes but also determine if Formula 1 can continue its impressive growth while preserving the excitement fans expect.

FAQs

How would a driver “soft cap” actually work?

A driver "soft cap" in Formula 1 would establish a flexible salary limit, aiming to manage costs without imposing strict restrictions. Teams would have the option to exceed the cap under certain conditions, though they might face penalties for doing so. The goal is to strike a balance between controlling expenses, maintaining competitive fairness, and ensuring teams can still attract top-tier drivers. Some exceptions could be made, such as allowances for marketing purposes or specific budget categories.

Would capping driver pay really make races closer?

Capping driver salaries in Formula 1 might help narrow the financial gap between teams, potentially resulting in tighter, more competitive races. On the flip side, critics worry it could restrict top drivers' earnings, which might impact their motivation or even lead to challenges in retaining elite talent. There's also concern that such a cap could deter young drivers from chasing F1 careers due to reduced financial incentives. Ultimately, how this impacts race competitiveness will hinge on the ripple effects it has on team strategies, driver performance, and how resources are distributed overall.

What happens to existing long-term driver contracts?

In Formula 1, long-term contracts typically stay in effect unless specific clauses permit early termination or renegotiation. Take Max Verstappen's multi-year agreement with Red Bull, which runs through 2028 - it offers stability for both parties but comes with potential risks, such as a dip in team performance or shifts in regulations. These contracts often cover areas like sporting commitments, commercial obligations, and image rights, giving both drivers and teams some room to adapt when necessary.