ERS in F1: Balancing Power and Efficiency

How F1's ERS captures braking and exhaust energy to boost power, shape race strategy and manage fuel and tyre wear — plus the 2026 electrification shift.

ERS (Energy Recovery System) in Formula 1 is a hybrid technology that transforms wasted energy - like braking and exhaust heat - into electrical power. This system, integrated with the 1.6-liter V6 turbo engine, boosts performance while adhering to strict fuel limits. ERS consists of:

- MGU-K: Recovers 2 MJ of braking energy per lap and deploys up to 4 MJ for acceleration.

- MGU-H: Converts exhaust heat into energy without limits, reducing turbo lag.

- Energy Store (Battery): Stores and deploys recovered energy.

- Control Electronics: Manages energy flow and deployment.

Introduced in 2014, ERS replaced the simpler KERS system, doubling power output and extending deployment time. It plays a key role in race strategy by managing energy to balance speed, fuel efficiency, and tire wear.

From 2026, F1 will increase ERS power to nearly 50% of total output, eliminate the MGU-H, and introduce 100% sustainable fuels, marking a major shift in energy management and racing dynamics.

ERS: What It Is and How It Works

From KERS to ERS: The Development of Energy Recovery

KERS vs ERS Evolution in Formula 1: Key Technical Differences

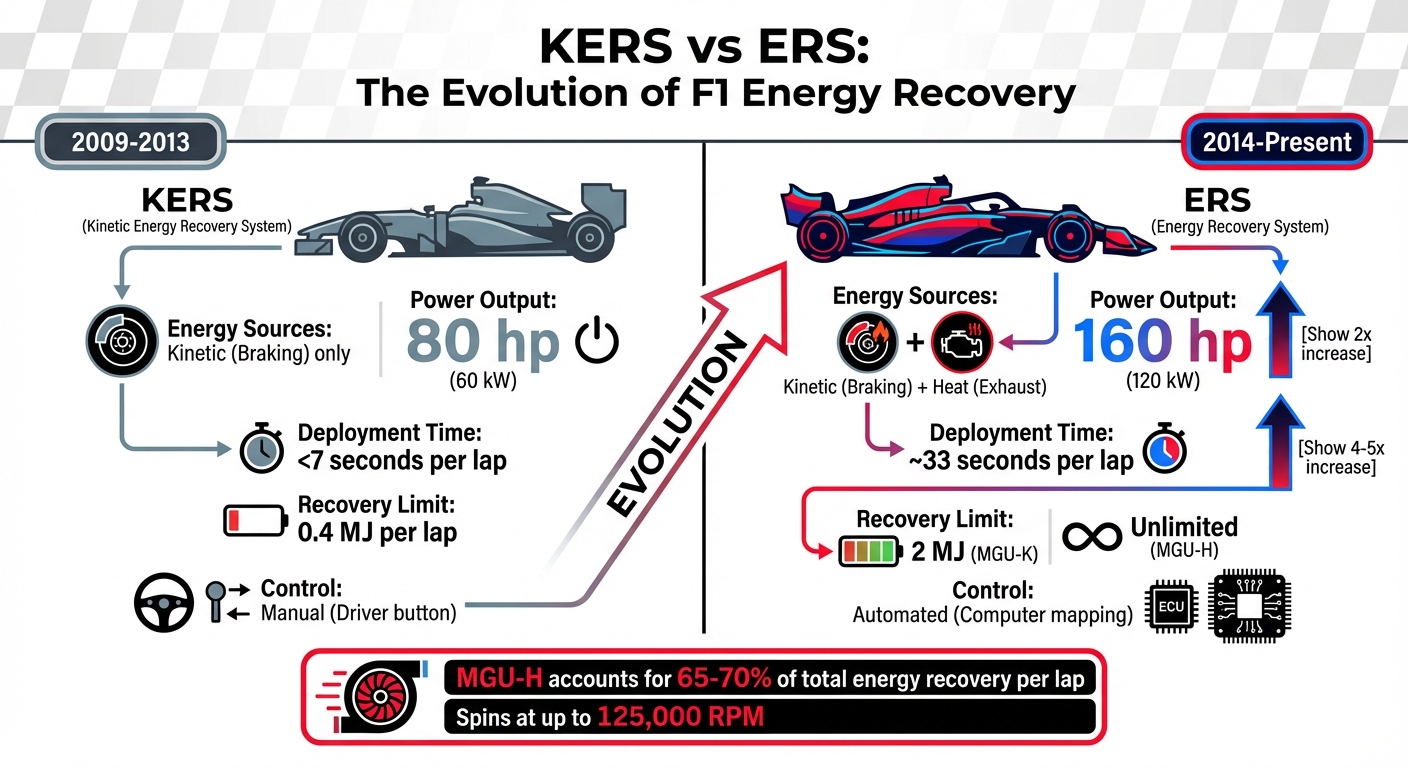

In 2009, Formula 1 introduced KERS (Kinetic Energy Recovery System), a bolt-on system designed to recover energy during braking. While it sounded promising, many teams initially avoided it due to the added weight, which often canceled out its benefits. KERS was relatively straightforward: it stored energy from braking and gave drivers a manual "boost" button to deploy an extra 80 hp (60 kW) of power for less than 7 seconds per lap. This made it more of a tactical overtaking tool than a fundamental performance feature.

Everything changed in 2014. New regulations ushered in hybrid power units, replacing KERS with the far more advanced ERS (Energy Recovery System). This wasn't just a tweak - it was a complete overhaul of how energy was captured and used. The new ERS doubled the power output to around 160 hp (120 kW) and extended deployment to roughly 33 seconds per lap. Unlike KERS, where drivers manually controlled the boost, ERS is fully automated. The car's Electronic Control Unit uses pre-set engine maps to manage energy flow and optimize performance throughout the lap.

A major leap came with the introduction of the MGU-H (Motor Generator Unit-Heat). This component captures thermal energy from exhaust gases - a massive untapped energy source that KERS couldn't utilize. The MGU-H alone accounts for 65% to 70% of an F1 car's total energy recovery per lap. Spinning at up to 125,000 RPM, it not only recovers energy but also eliminates turbo lag by keeping the compressor spinning even when the driver isn't on the throttle.

Today’s ERS systems combine several sophisticated components, working together to maximize both efficiency and power.

Main Components of ERS

Modern ERS systems are highly integrated, consisting of four main components:

- MGU-K (Motor Generator Unit-Kinetic): Attached to the crankshaft, it converts braking energy into electricity, with a recovery cap of 2 MJ per lap.

- MGU-H (Motor Generator Unit-Heat): Connected to the turbocharger shaft, it recovers heat energy from exhaust gases. Unlike the MGU-K, there are no recovery or deployment limits for the MGU-H.

- Energy Store (ES): A lithium-ion battery weighing between 20 kg and 25 kg, it stores all harvested energy until needed.

- Control Electronics (CE): The system's "brain", it manages energy flow between the MGUs and the battery, ensuring compliance with FIA regulations. It decides when to store energy, when to deploy it, and how to balance power and efficiency demands.

This intricate coordination is a far cry from the simplicity of KERS's push-button system.

KERS vs. ERS: What Changed

The evolution from KERS to ERS highlights how far Formula 1's hybrid technology has come. While KERS provided a brief burst of extra power, ERS delivers continuous performance enhancements, seamlessly integrated into the car’s operation.

| Feature | KERS (2009–2013) | ERS (2014–Present) |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Sources | Kinetic (Braking) only | Kinetic (Braking) + Heat (Exhaust) |

| Deployment | Manual (Driver button) | Automated (Computer mapping) |

| Recovery Limit | 0.4 MJ per lap | 2 MJ (MGU-K) + Unlimited (MGU-H) |

ERS has transformed energy recovery from a secondary feature into a core element of modern F1 power units. However, this leap in technology comes with challenges. For instance, during the 2019 Bahrain Grand Prix, Daniel Ricciardo's Renault displayed red ERS status lights, signaling an electrical safety issue. He had to retire and "jump from the car" without touching its body to avoid electrocution. Incidents like this underscore both the incredible power and the risks of these high-voltage systems operating at the cutting edge of technology.

This shift in energy recovery has not only revolutionized power delivery but also reshaped race strategies, as teams now rely heavily on managing these systems to gain a competitive edge. The impact of these advancements will be explored further in the following sections.

How ERS Recovers and Deploys Energy

The Energy Recovery System (ERS) plays a critical role in modern racing by capturing energy that would otherwise go to waste and turning it into power that drivers can use strategically. When a driver brakes or when exhaust gases spin the turbine, the system harvests this energy, stores it in the battery, and releases it at key moments during the race.

This entire process is controlled by the car's Electronic Control Unit (ECU). The ECU uses pre-set energy maps to decide when to store energy and when to deploy it. Drivers also have the option to manually activate "Overtake" modes for a quick power boost. This balance between automated precision and driver input is what makes ERS so effective. To fully understand its functionality, it's important to look at the roles of its key components.

One standout feature of the ERS is how the MGU-K and MGU-H work together. The MGU-K can recover 2 MJ per lap and deploy up to 4 MJ, while the MGU-H recovers additional energy without any limits. Managing the battery's state of charge (SOC) is essential to ensure there’s enough energy available throughout the lap.

MGU-K: Recovering Energy from Braking

The MGU-K (Motor Generator Unit-Kinetic) is attached to the engine's crankshaft and can operate at speeds of up to 50,000 RPM. Every time the driver brakes, the MGU-K acts like a generator, converting kinetic energy into electrical energy, which is then stored in the battery. This energy recovery happens at every braking zone on the track. It’s worth noting that the MGU-K connects to the crankshaft, not the brakes themselves.

When it’s time to deploy energy, the MGU-K switches roles to act as a motor, delivering extra power to the car. However, there’s a restriction at race starts: the MGU-K can only provide a power boost once the car reaches 100 kph (60 mph).

MGU-H: Using Exhaust Heat

The MGU-H (Motor Generator Unit-Heat) captures energy from the heat in the exhaust gases. It’s mounted on the turbocharger shaft, positioned between the turbine and compressor, and can operate at speeds of up to 125,000 RPM. As exhaust gases leave the engine, they spin the turbine, allowing the MGU-H to convert this thermal energy into electricity. Unlike the MGU-K, there are no limits on how much energy the MGU-H can recover or deploy.

Storing and Using Energy During a Race

Once energy is recovered by the MGU-K and MGU-H, it is stored in the Energy Store, a lithium-ion battery that operates at voltages as high as 1,000V. To ensure safety, F1 cars have status lights on their airbox: a green light means the car is safe to touch, while a red light warns of potential electrical hazards.

Balancing energy recovery and deployment is a constant challenge. The MGU-K’s 2 MJ per lap recovery limit, combined with its ability to deploy up to 4 MJ, means that any additional energy must come from the MGU-H. If the MGU-H doesn’t recover enough energy, the battery’s charge can drop, forcing drivers to reduce energy use and potentially lose precious time on the track.

Strategic energy deployment is critical for success. Teams create different energy maps tailored for qualifying and race conditions, and drivers must decide when to use stored energy - whether to overtake an opponent or defend their position. This delicate balance between maximizing performance and conserving energy adds another layer of complexity to Formula 1 racing.

Managing Power Output and Efficiency with ERS

Formula 1 teams constantly juggle performance optimization with staying within strict technical rules and managing their cars' physical limits. Using the Energy Recovery System (ERS) effectively is a key part of this balancing act. The goal? Deploy energy smartly without compromising fuel efficiency or causing unnecessary tire wear.

Working Within Fuel Flow Limits

Modern F1 engines are capped at a strict fuel flow limit of 100 kg/hr, which restricts the power the internal combustion engine can generate on its own. This limitation makes ERS a game-changer. According to regulations:

"the amount of petrol going into the engine is limited, restricting the revs and the power that can be produced and encouraging the teams to design more efficient engines".

ERS compensates for this limitation by adding up to 160 horsepower without burning extra fuel, allowing drivers to maintain competitive lap times even under these restrictions. However, using ERS aggressively can drain the battery, leading to performance dips. The MGU-K’s limited energy recovery capacity creates a gap that the MGU-H must fill. If the MGU-H can’t recover enough energy from the exhaust, the battery runs low, forcing drivers to ease off for at least two laps to recharge.

Teams tailor ERS deployment modes based on race conditions. During qualifying, drivers use all available battery power for their fastest lap. In races, they switch to more conservative modes, ensuring the battery holds enough charge for crucial moments like overtaking or defending. Beyond fuel considerations, how ERS is deployed also directly impacts tire performance.

ERS Effects on Tire Wear

ERS management isn’t just about energy - it heavily influences tire wear. Activating ERS mid-corner or on corner exits delivers an extra 160 horsepower, which can upset the car’s balance and cause rear tires to spin. This accelerates wear, requiring drivers to modulate throttle input carefully to avoid wheel spin.

Teams rely on advanced strategies to balance lap times and tire preservation. Sometimes, slowing down slightly is the smarter choice for long-term performance. For example, Charles Leclerc’s victory at the September 2024 Italian Grand Prix showcased this approach. He used a risky one-stop strategy, maintaining consistent lap times of around 83 seconds while managing tire degradation over an extended stint. Similarly, telemetry from the 2025 Canadian Grand Prix revealed Max Verstappen kept his tires at an optimal temperature of 94.9°C, achieving steady lap times of 73.2–73.4 seconds. In contrast, Lewis Hamilton’s tires ran hotter at 95.6°C, leading to more variable lap times of 73.4–73.9 seconds.

Techniques like "lift-and-coast" and brake balance adjustments help manage tire wear without sacrificing speed. Lift-and-coast involves easing off the throttle before braking zones, reducing tire stress with minimal impact on lap times. Adjusting brake balance forward during high-energy recovery phases also protects rear tires by minimizing slip. Even small changes matter - a 10°C increase in wheel rim temperature can raise tire carcass temperature by 1°C. Teams carefully monitor and manage this relationship using brake bias and ERS-related braking energy.

ERS in Race Strategy

ERS deployment is a tactical tool that plays a key role in overtaking, defending, and conserving energy for those pivotal moments in a race. Teams weave energy management into their overall strategy, often making the difference between a podium finish and falling behind. These tactical decisions build on the technical foundations discussed earlier, shaping how teams approach each race.

Different ERS Deployment Modes

Teams rely on pre-programmed ERS deployment modes to fine-tune performance for specific situations. Drivers can switch between these modes using buttons on the steering wheel, allowing them to manage the release of the system's 4 MJ of energy per lap. Common modes include maximum output for qualifying, a quick burst for overtaking, and a more balanced setting for race consistency.

However, there's a challenge: the system can only recover 2 MJ per lap, creating a gap between recovery and deployment. For instance, draining the battery for a single fast lap means drivers often need two laps of recharging to restore full capacity. The MGU-H, though, offers a critical advantage by recovering energy from exhaust gases, extending the boost potential beyond what the battery alone can provide. Interestingly, the MGU-H accounts for 65–70% of an F1 car's total energy recovery over a lap.

Track design also heavily influences how teams deploy ERS. At high-speed circuits like Monza, energy is conserved for key straights, while technical tracks like Monaco focus on frequent recharging, with drivers recovering energy in heavy braking zones. Mixed circuits like Spa demand a balanced approach, optimizing energy for critical high-power sections.

When defending, drivers use ERS to maintain higher top speeds on straights, making overtaking more difficult - even for rivals using DRS. While automated systems manage much of the energy deployment, drivers can override these settings for tactical moves, adding another layer of strategy.

How Top Teams Use ERS Differently

Top teams set themselves apart by tailoring energy management strategies to their car's strengths. During qualifying, they often drain the full 4 MJ in a single flying lap to shave off every possible fraction of a second. In races, the focus shifts to managing the state of charge, ensuring enough energy is available for sustained performance and overtaking opportunities.

Efficiency in components like the MGU-H gives some teams an edge. Those with highly efficient systems can maintain higher energy levels throughout a stint, giving their drivers more flexibility in deployment choices.

Despite the advanced automated systems, driver input remains essential. The sudden boost of 160 hp from ERS deployment can affect the car's balance, especially when accelerating out of corners. Top drivers master the art of modulating throttle and coordinating ERS activation with steering inputs, ensuring maximum acceleration without destabilizing the car. This precision often separates the best drivers from the rest of the grid.

Conclusion: What's Next for ERS in F1

The Energy Recovery System (ERS) has reshaped Formula 1 by combining raw power with strategic precision. We've explored how the MGU-K captures braking energy, how the MGU-H utilizes exhaust heat, and how these systems work together to manage fuel flow, tire wear, and energy deployment. Impressively, ERS has boosted fuel efficiency by about 35% compared to older engine designs, highlighting its role in both performance and sustainability.

Looking ahead, upcoming regulations are set to redefine ERS technology. In 2026, the electrical system's share of total power will increase from around 20% to nearly 50%. The MGU-K will see a dramatic power boost - nearly tripling its current output - while the MGU-H, which currently accounts for 65–70% of energy recovery per lap, will be eliminated entirely to cut costs and attract new manufacturers.

Sustainability is now steering the future of F1 innovation. Starting in 2026, all teams will transition to 100% advanced sustainable fuels, following trials in Formula 2 and Formula 3 during the 2025 season. This shift, paired with greater electrification, aligns with F1's goal to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2030. Beyond racing, these advancements could pave the way for improvements in hybrid and electric vehicles for everyday use.

These changes will also bring new dynamics to race strategy. The traditional Drag Reduction System (DRS) will be replaced by "Overtake Mode", which delivers extra electrical power when a driver is within one second of a rival car. Additionally, drivers will gain more control over lift-off regeneration, while activating "Recharge" mode will disable active aero devices to maximize energy recovery. These updates will demand fresh strategic thinking from teams and drivers, adding a new layer of complexity to energy management that could determine who stands on the podium.

FAQs

What changes will the removal of the MGU-H in 2026 bring to F1 strategies?

The elimination of the MGU-H in 2026 represents a major change in how F1 power units are designed and managed. Without the option to recover and use heat energy from the turbo, teams will need to lean more on the MGU-K, which captures kinetic energy during braking.

This shift will force teams to prioritize getting the most out of energy recovery and deployment through the MGU-K, all while maintaining a careful balance between performance and efficiency. It’s likely to influence race strategies as well, with energy management playing an even bigger role in achieving the right mix of speed and fuel efficiency.

What are the advantages of using 100% sustainable fuels in Formula 1?

Switching to 100% sustainable fuels in Formula 1 offers a range of benefits that align with the sport's ambitious environmental goals. These fuels are created using renewable sources such as biomass, municipal waste, or synthetic processes powered by renewable energy. By doing so, they significantly cut greenhouse gas emissions, playing a key role in F1's mission to reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2030 - all while ensuring the high-performance racing fans love remains unchanged.

One of the standout features of sustainable fuels is their compatibility with existing engines. They are designed as drop-in solutions, meaning teams and manufacturers can adopt them without making any modifications to their current setups. Beyond convenience, these fuels are expected to slash emissions by at least 65%, shrinking F1's carbon footprint and paving the way for innovations that could influence the wider automotive world.

How do the MGU-K and MGU-H work together to improve F1 car performance?

The MGU-H takes heat energy from the exhaust and turns it into electricity, helping to cut down on turbo lag and improve engine efficiency. On the other hand, the MGU-K captures kinetic energy during braking and can add up to 161 horsepower directly to the drivetrain, providing an extra burst of acceleration. Together, these systems enhance power output while keeping fuel consumption and tire wear in check - key factors in modern F1 performance.