Evolution of F1 Wet Tires: Key Milestones

Full-wet F1 tires are advanced but often sidelined by massive spray and a 6–7s pace deficit; Pirelli aims to cut spray and close the wet/intermediate gap by 2026.

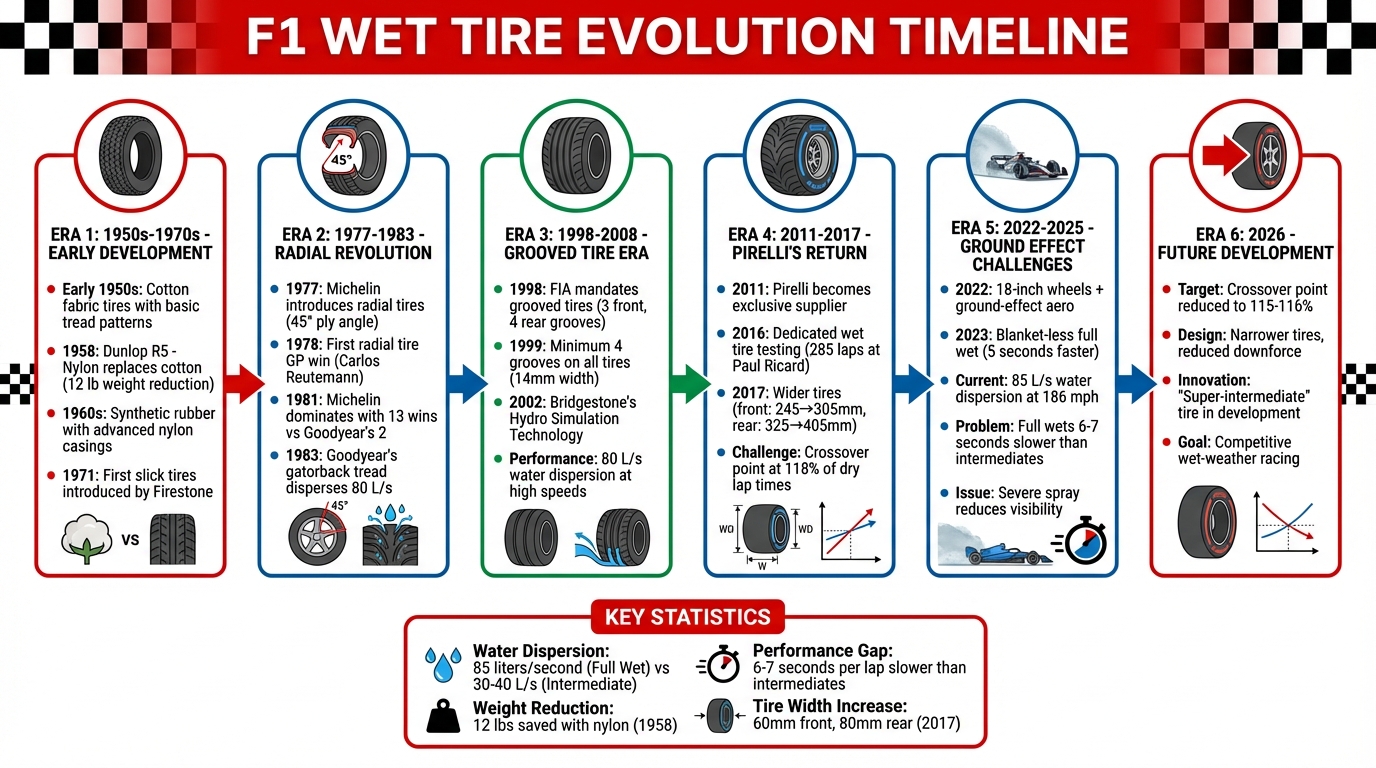

When Formula 1 cars race on wet tracks, specialized tires are essential. Modern full wet tires can channel away up to 85 liters of water per second at speeds of 186 mph, preventing hydroplaning and ensuring control. Over the decades, advancements in materials, construction, and tread design have transformed wet-weather performance. However, the introduction of ground-effect aerodynamics in 2022 has created a new challenge: severe spray reducing visibility, often leading to red-flagged races before full wets are even used.

Key developments include:

- 1950s-1970s: Early treaded tires evolved with nylon replacing cotton, reducing weight and improving grip.

- 1977-1983: Michelin's radial tires offered better water dispersion and consistent grip.

- 1998-2008: Grooved tires boosted water handling but limited dry performance.

- 2011-Present: Pirelli's return introduced blanket-less wet tires and wider dimensions, improving water management but increasing spray issues.

Despite these advancements, full wet tires are often criticized for being 6-7 seconds slower per lap than intermediates, limiting their use to Safety Car conditions. Pirelli is now working to improve the performance gap and reduce spray for the 2026 season, aiming to make wet-weather racing safer and more competitive.

Evolution of F1 Wet Tire Technology from 1950s to 2026

Early Development: 1950s-1970s

From Treaded Tires to Slicks

In the early days of Formula 1, all tires came with treaded designs - there were no specialized options for wet or dry conditions. Between 1950 and the late 1960s, teams relied on these multipurpose treaded tires, regardless of the track's surface or weather. That changed in 1971 when Firestone introduced slick tires specifically for dry conditions during the Spanish Grand Prix.

The grooves in treaded tires helped channel water away in wet conditions, while still maintaining some grip on dry surfaces. Companies like Dunlop produced early models, such as the cotton-based R1–R4 tires, which were not only heavy but also wore down quickly. These early designs laid the groundwork for future breakthroughs that would redefine tire performance.

The Shift to Synthetic Materials

In 1958, Dunlop made a significant leap with the R5 tire, which replaced traditional cotton with nylon. This change reduced the tire's weight by 12 pounds, improving both handling and suspension response.

During the 1960s, tire manufacturers continued to refine their designs. They began using synthetic rubber paired with advanced nylon casings, which offered better grip and water resistance compared to the earlier natural rubber and cotton combinations. These innovations allowed for the development of narrower tire profiles and wider contact patches, improving stability and control. The enhanced grip provided by these advancements was especially critical in maintaining traction on wet tracks.

| Era | Primary Material | Key Innovation | Performance Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early 1950s | Cotton Fabric | Basic Treaded Patterns | Standard grip; heavier and wore quickly |

| Late 1950s | Nylon Fabric | Dunlop R5 Tire | 12 lb weight reduction; better durability |

| 1960s | Synthetic Rubber | Advanced Nylon Casings | Wider tires; improved grip and stability |

Radial Tire Technology: 1977-1983

How Radial Construction Improved Wet Performance

In 1977, Michelin made waves in Formula 1 by introducing radial tires. Unlike traditional designs with plies set at 90°, these tires featured plies angled at roughly 45°, allowing for a consistent contact patch. This design also improved water dispersion, enhancing grip and stability, especially under the intense aerodynamic loads of F1 cars.

The impact was immediate. In 1978, Carlos Reutemann became the first driver to win a Grand Prix using Michelin's radial tires at the Brazilian Grand Prix. By 1981, the results spoke for themselves: Michelin-equipped cars secured 13 victories, while Goodyear managed only two. This success pushed other manufacturers to start developing their own radial tire technologies.

Goodyear's Rain-Specific Radial Tire

Inspired by Michelin's advancements, Goodyear introduced its own rain-specific radial tire in 1983. The standout feature was its gatorback tread, designed to evacuate water quickly and provide better traction on wet tracks. This innovation was a game-changer for wet-weather racing strategies. However, radial construction brought its own challenges; drivers had to adjust to smaller slip angles, which altered the handling dynamics.

During the 1983 season, Goodyear tires contributed to six race wins, while Michelin continued to dominate with nine victories. Notably, Goodyear's monsoon tires could disperse up to 80 liters of water per second, setting a new benchmark for wet-weather performance. This level of efficiency highlighted the rapid evolution of tire technology during this period.

The Incredible Evolution of F1 Tyres

Grooved Tires: 1998-2008

The introduction of grooved tires signaled a new chapter in the quest to balance speed, performance, and safety on the track.

FIA Regulations and the Shift to Grooved Tires

In 1998, the FIA introduced regulations requiring grooved tires to reduce mechanical grip and curb excessive cornering speeds. Initially, front tires needed three grooves, while rear tires required four. By 1999, the rules mandated at least four grooves on all tires, each measuring a minimum of 14 mm (0.55 inches) in width. This effectively ended the dominance of slick tires in Formula 1.

The shift to grooved designs posed unique challenges for tire manufacturers. To maintain tread block integrity, harder rubber compounds became necessary. While this adjustment decreased tire forgiveness in certain conditions, it brought notable improvements in wet-weather performance by enhancing water dispersion and minimizing the risk of aquaplaning.

Advancements in Water Dispersion Technology

Grooved tires significantly boosted water-handling capabilities. Full wet tires could disperse up to 80 liters of water per second at high speeds, while intermediate tires managed 35–40 liters per second at 300 km/h (186 mph).

Bridgestone made strides in this area with its "Hydro Simulation Technology", which used computer modeling to analyze water flow beneath the tire. This allowed engineers to refine tread patterns for better efficiency. The technology's impact was evident during the July 2002 British Grand Prix at Silverstone. In heavy rain, Ferrari drivers Michael Schumacher and Rubens Barrichello achieved a 1-2 finish, with six of the top seven cars running on Bridgestone tires.

One of the main engineering hurdles was managing the "land:sea ratio", which measures the balance between the rubber contact patch and the grooves designed for water drainage. Bridgestone's Technical Manager, Hisao Suganuma, explained the complexity:

"If one increases the sea ratio [the number of grooves], the blocks will be smaller, which means there is less contact patch on the road. This causes more force to be put through the blocks which, in turn, causes more movement in the tire. This can make the car feel unstable and ultimately make it slower."

The grooved tire era came to an end in 2008, with Formula 1 reverting to slick tires for dry conditions. However, the advancements in wet-weather tire technology during this period set the stage for modern innovations in tire design.

Pirelli's Developments: 2011-Present

When Pirelli returned as Formula 1's exclusive tire supplier in 2011, the company set out to redefine wet weather tire performance. Building on the lessons from the grooved tire era, the Italian manufacturer prioritized advanced polymer compounds to tackle grip and thermal management issues that had previously hindered performance.

Pirelli's Return and New Compounds

After re-entering the sport, Pirelli identified that drivers’ complaints about aquaplaning were actually linked to unstable tread blocks, which compromised cornering grip. The deep grooves meant to combat aquaplaning created smaller tread blocks that shifted excessively under load, generating heat and leading to overheating. As Mario Isola, Pirelli's Head of Motorsport, explained:

If those blocks move, you generate heat and that means that we had overheating of the wet tire. It seems a joke, but it's true!

To address this, Pirelli revamped its tread patterns and, in 2023, introduced a blanket-less full wet compound. This innovation significantly improved performance, cutting lap times by roughly 5 seconds.

One of Pirelli's key objectives has been narrowing the "crossover point" - the performance threshold where drivers switch between intermediate and full wet tires. Currently, this threshold stands at about 118% of dry lap times. Pirelli is working to lower it to 115–116%, ensuring full wet tires are competitive rather than just suitable for Safety Car conditions. In January 2016, a dedicated wet tire test at Paul Ricard saw teams like Ferrari, McLaren, and Red Bull, along with drivers such as Sebastian Vettel and Kimi Räikkönen, complete 285 laps in a single day to refine this threshold for the 2016 season.

These developments laid the groundwork for further innovations, including significant changes in tire dimensions introduced in 2017.

Wider Tires in 2017

The 2017 season brought major regulatory changes, with tire dimensions increasing substantially. Front tires grew from 245 mm to 305 mm (9.6 to 12 inches), and rear tires expanded from 325 mm to 405 mm (12.8 to 15.9 inches). Additionally, the overall tire diameter increased by 10 mm, which boosted both grip and water dispersion capabilities.

The wider tires improved mechanical grip and enhanced water dispersion, with full wet tires capable of dispersing large amounts of water at high speeds. Intermediates, for example, manage 30–40 liters per second. The increased diameter also slightly raised the car’s floor, aiding in water clearance.

However, these benefits came with new challenges, particularly in managing spray. The wider tires generated significant plumes of spray, severely reducing visibility for drivers following behind. This issue became even more pronounced with the introduction of ground-effect cars in 2022. As George Russell observed, the full wet tire remains significantly slower, often adding six to seven seconds per lap.

Looking ahead to 2026, Pirelli is testing prototypes with slightly reduced width and external diameter, while keeping the 18-inch rim diameter introduced in 2022. In January 2025, Oscar Piastri conducted 120 laps at Paul Ricard to evaluate these new specifications.

Compound Ranges and Race Strategy: 2019-2025

Changes to Compound Ranges

In response to evolving tire technology and the growing challenges of water displacement, Pirelli made significant updates to its compound lineup. Back in 2019, the company simplified its dry tire offerings to five compounds, labeled C1 through C5. By 2025, this range expanded to six options, adding a C6 compound. Meanwhile, the wet-weather lineup remained consistent, featuring the green-marked Intermediate (with a 3 mm tread) and the blue-marked Full Wet (with a 5 mm tread). The transition to 18-inch wheels in 2022 brought further changes, particularly in wet tire design. The Full Wet compound was reengineered to handle an impressive 85 liters of water per second at speeds of 186 mph (300 km/h) - a capability nearly three times greater than the Intermediate, which manages 30–40 liters per second.

In 2023, Pirelli introduced a new Full Wet compound that eliminated the need for tire blankets, a move aimed at improving efficiency. Testing revealed that this blanket-less tire delivered a 5-second-per-lap improvement. However, despite this progress, the Full Wet remained 6–7 seconds per lap slower than the Intermediate under race conditions. This led drivers like George Russell to voice their frustrations:

The extreme wet tyre is a pretty pointless tyre... really, really bad. It's probably six, seven seconds a lap slower than the intermediate.

These changes in tire performance set the stage for notable shifts in race-day strategies.

Effects on Race Strategy

The advancements in tire technology directly reshaped how teams approached wet-weather racing between 2019 and 2025. The performance gap between the Full Wet and the Intermediate led teams to treat the Full Wet as a "Safety Car tire", primarily using it during neutralized sessions when mandated. Once racing resumed, teams quickly switched to Intermediates at the earliest opportunity. A clear example of this approach was seen during the Sprint Race at the July 2023 Belgian Grand Prix. Initially, all cars were required to run on Full Wets behind the Safety Car. However, about half the field switched to Intermediates as soon as the rolling start began, while the rest followed suit just one lap later.

Race strategy in wet conditions often hinged on mastering the "crossover point" - the moment when one compound becomes faster than another. This was evident at the July 2019 German Grand Prix, where Max Verstappen and Red Bull Racing clinched victory by skillfully navigating multiple transitions between slicks, Intermediates, and Full Wets. Meanwhile, several front-runners, including Lewis Hamilton and Charles Leclerc, fell victim to poor tire choices and lost control. By 2025, teams had become adept at pushing the limits of the Intermediate tire, even in extreme conditions. During the July 2025 British Grand Prix at Silverstone, Lando Norris and McLaren gambled on a fresh set of Intermediates despite heavy rain. While the strategy paid off, Norris later admitted to experiencing "scary moments" due to aquaplaning.

Despite these strategic adjustments, the Full Wet tire continued to face criticism. Pirelli had aimed for a crossover point where the Full Wet would perform at 115–116% of dry lap times, but in practice, its performance hovered closer to 118%. As Mario Isola, Pirelli’s Head of Motorsport, candidly remarked:

If the full wet tyre is used only behind the safety car, I agree with drivers that, at the moment, it is a useless tyre.

Conclusion

While early breakthroughs laid the foundation, modern tire compounds have pushed performance to new heights. Yet, the full wet tire finds itself in a precarious position. With a lap time deficit of 6–7 seconds compared to intermediates, it has earned the nickname "Safety Car tire" among drivers and teams.

The main obstacle in wet-weather racing today isn’t tire grip - it’s visibility. The ground-effect aerodynamics introduced in 2022 send water high into the air, creating a dense spray that drastically reduces sightlines for drivers. This evolution in aerodynamics has introduced a new layer of complexity to wet racing.

Looking ahead, Pirelli is focusing on advancements for 2026. Mario Isola, Pirelli's Head of Motorsport, shared their goals:

For 2026, our first target is to improve the crossover point between the intermediates and the full wets, so teams can choose one or the other without losing performance.

Pirelli plans to lower the crossover from 118% to 115–116% of dry lap times. They are also exploring the development of a "super-intermediate" tire to better address a wider range of wet conditions.

The 2026 regulations will introduce narrower tires and reduced downforce, which could help reduce the spray issue that has plagued recent seasons. Additionally, research into solutions like spray guards and wheel arches signals a shift from merely coping with wet conditions to striving for competitive wet-weather performance. After seven decades of progress, the evolution of F1 wet tires now stands at a critical juncture, where visibility and aerodynamics are as vital as compound chemistry and tread innovation.

FAQs

How have advancements in F1 wet tires influenced race strategies?

Modern developments in wet tire technology have turned rain-soaked races into strategic opportunities rather than interruptions focused solely on safety. Today’s full wet tires can disperse up to 85 liters of water per second at speeds of 186 mph. This capability dramatically enhances grip and control, even in heavy rain. On top of that, newer tire designs are narrowing the performance gap between full wet and intermediate tires, letting teams stick with full wets longer and reduce the need for frequent pit stops.

These advancements are reshaping race strategies. Teams can now switch to full wets earlier during rainstorms without sacrificing track position. The smaller gap in performance between tire types also gives teams more flexibility to extend stints, especially when improved aerodynamics help reduce visibility problems. Plus, modern wet tires are built to maintain their ideal temperature range for longer periods, cutting down on premature pit stops and enabling more competitive and dynamic racing, even under challenging wet conditions.

What makes ground-effect aerodynamics challenging during wet-weather F1 races?

Ground-effect aerodynamics work by channeling smooth, high-speed airflow under the car to generate downforce. But when the track is wet, this system runs into trouble. Water spray disrupts the airflow, weakening the low-pressure zone that’s key to producing ground-effect downforce. The introduction of larger 18-inch wheels and wider tires has only made things worse. These tires can displace up to 22.5 gallons of water per second at speeds of 186 mph, creating a dense spray that hampers visibility and airflow efficiency.

Wet conditions also compromise the low-pressure seal beneath the car, further reducing downforce. To adapt, teams often tweak car setups - like raising the ride height or adjusting wing angles - to balance mechanical grip and reduce spray. However, these adjustments come at a cost, as they hurt aerodynamic performance. Combine this with slippery traction and limited visibility, and it’s easy to see why wet-weather racing becomes so tricky. These challenges often lead to race stoppages during heavy rain.

Why do full wet tires face criticism compared to intermediate tires in F1?

Full wet tires, easily recognized by their blue sidewalls, often stir debate because they tend to cause more problems than they solve unless the rain is absolutely torrential. With deep treads and a wide 16-inch diameter, these tires can channel over 22 gallons of water per second at speeds of 186 mph. While that sounds impressive, the downside is the massive spray they generate, which drastically reduces visibility for drivers behind - a significant safety risk. Because of this, teams usually reserve them for only the most extreme conditions.

Another drawback is their limited performance range. Full wets only start to shine when lap times drop to roughly 115–118% of the typical dry pace, a scenario that’s uncommon before a race is halted due to heavy rain. On top of that, drivers often struggle to get these tires up to the right temperature, and they quickly lose effectiveness as the track begins to dry. In most wet situations, intermediate tires prove to be the faster and more practical choice.