How F1 Drivers Handle Braking in the Rain

F1 drivers brake earlier off the racing line, modulate pedal pressure, avoid trail braking, follow tire tracks and use trackside cues to avoid aquaplaning.

In wet conditions, Formula 1 drivers face unique challenges when braking. Rain reduces grip, turns the usual racing line into a slick hazard, and increases the risk of aquaplaning. Without ABS, drivers must manually control brake pressure and adjust their techniques to maintain control. Here's how they manage:

- Brake earlier: Wet tracks require braking sooner, often off the rubbered racing line, where grip is better.

- Smooth pressure application: Abrupt braking causes wheel lock-up; drivers apply and release pressure gradually.

- Avoid trail braking: Drivers brake in a straight line before corners to minimize combined braking and turning forces.

- Combat aquaplaning: They follow tire tracks to reduce water and avoid puddles or standing water.

- Use visual cues: In low visibility from spray, drivers rely on trackside markers to judge braking points.

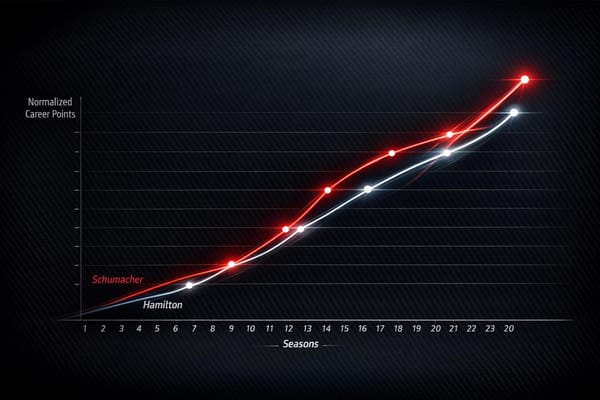

Legends like Ayrton Senna and Michael Schumacher excelled in wet-weather braking by finding grip in unconventional areas. Modern drivers like Lewis Hamilton and Max Verstappen continue to showcase mastery in these conditions. Wet-weather braking demands precision, quick adjustments, and a deep understanding of the car's limits.

Secrets to Winning in the Wet (Explained)

Why Rain Changes Braking Performance

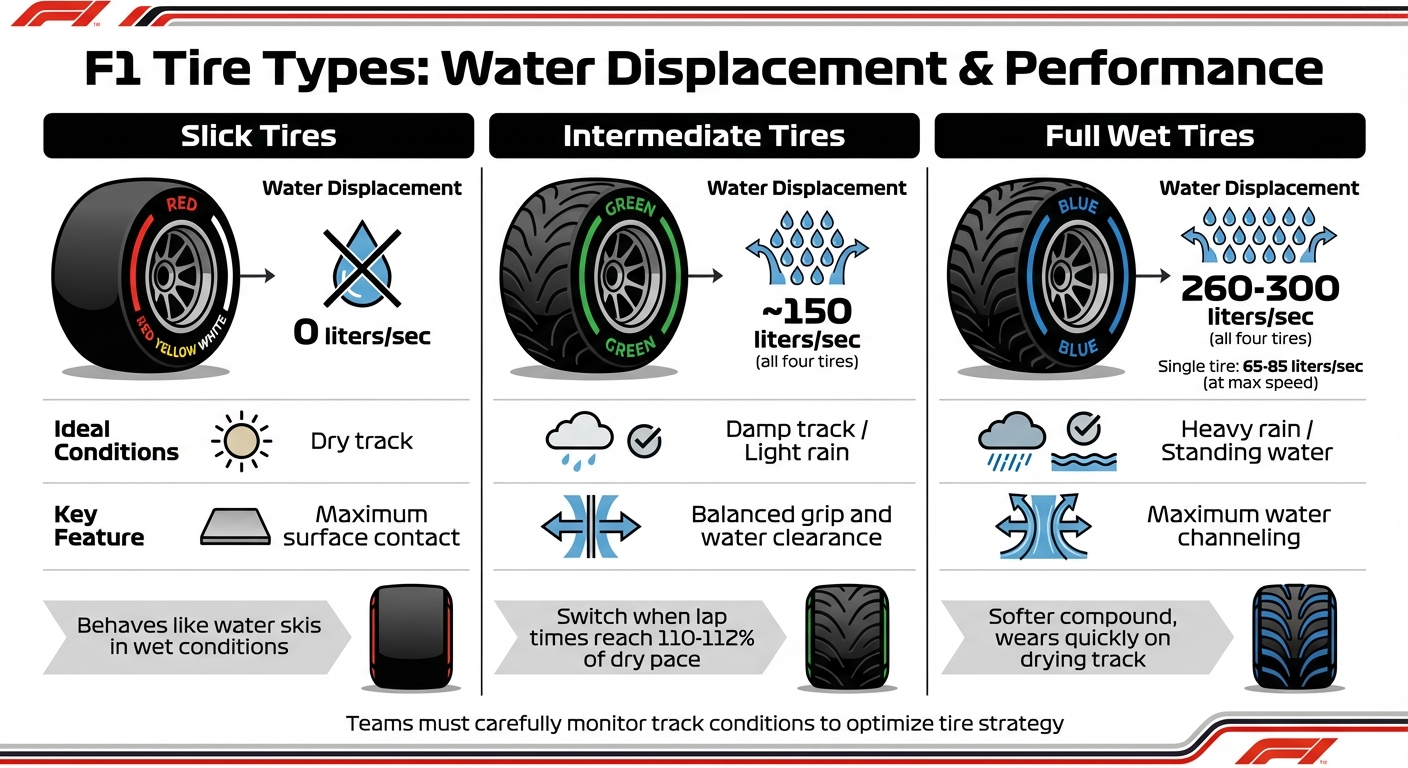

F1 Tire Types Comparison: Water Displacement and Performance in Different Conditions

Reduced Grip on Wet Tracks

When rain hits the track, the usual rules for grip and control are flipped. On a dry circuit, the racing line - the path worn smooth by repeated laps - provides the best traction. But in wet conditions, that same rubbered surface becomes dangerously slippery, almost like black ice. Drivers are forced to abandon their familiar routes and search for grip on cleaner sections of asphalt, typically about 3 meters away from the traditional racing line. With reduced cornering speeds and less aerodynamic downforce in the rain, braking in a straight line becomes essential to make the most of the limited traction available. These challenges demand significant adjustments to braking techniques, which we’ll explore further.

Aquaplaning and Water Displacement

Aquaplaning happens when tires fail to clear standing water quickly enough, causing the car to float on a thin layer of water rather than gripping the track. In these moments, steering and braking inputs lose their effectiveness because there’s almost no friction to work with. As Scott Mansell puts it, aquaplaning can make even the most skilled driver feel powerless.

To combat this, Pirelli’s full wet tires are designed with deep grooves that can channel away between 65 and 85 liters of water per second at maximum speed. Despite this impressive engineering, heavy rain can still overwhelm the tires’ capacity, forcing drivers to avoid puddles and waterlogged areas that could lead to a sudden, uncontrollable slide.

Wet vs. Dry Tire Performance

The difference between slick and wet tires lies in their design and purpose. Slick tires, used in dry conditions, have no grooves, which maximizes the surface area in contact with the track. This design delivers optimal grip on a dry surface but makes slicks almost useless in the wet, where they behave more like water skis.

Wet tires, on the other hand, are equipped with channels and blocks that help disperse water, allowing the rubber to maintain contact with the track. These tires also feature softer rubber compounds, which perform better at the cooler temperatures typical of rainy conditions. However, this softness comes at a cost - wet tires wear out quickly on a drying track. Teams must pay close attention to track conditions and switch to intermediates or slicks as soon as the racing line begins to dry. This usually happens when lap times approach 110–112% of the typical dry pace.

| Tire Type | Sidewall Color | Water Displacement | Ideal Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Slick | Red/Yellow/White | 0 liters/sec | Dry track |

| Intermediate | Green | ~150 liters/sec (all four tires) | Damp / Light rain |

| Full Wet | Blue | ~260–300 liters/sec (all four tires) | Heavy rain / Standing water |

Wet tires are a lifesaver in poor weather, but they’re not a one-size-fits-all solution. As the track dries, teams must carefully balance tire performance and durability to stay competitive.

How Drivers Adjust Their Braking in the Rain

When the rain starts falling, drivers must rethink their braking strategies to tackle the challenges of reduced grip and the risk of aquaplaning. Adjusting to these slippery conditions requires precision and adaptability. Here’s how they do it:

Braking Earlier and Off the Racing Line

In wet conditions, the usual racing line becomes a hazard. The rubber laid down on the track, which provides excellent grip in the dry, transforms into a surface as slick as black ice when wet. To counter this, drivers brake earlier - sometimes up to 15 feet before their usual spot - and move off the traditional racing line. They aim for cleaner sections of asphalt where the grip is better.

With rain reducing visibility and spray obscuring the corner apex, drivers turn to trackside markers for guidance. Peripheral vision becomes crucial as they use cues like marshal posts, advertising boards, or curbs to judge their braking points.

Gradual Brake Pressure Application

Rainy conditions call for a delicate touch on the brake pedal. Aggressive, sudden braking - common on a dry track - simply won’t work. Professional driver Scott Mansell emphasizes the importance of smooth, controlled pressure:

"The pedals really need to be 'squeezed' on and off. If you require deceleration in a corner your foot should 'breathe' off the pedal rather than panicking and coming off completely."

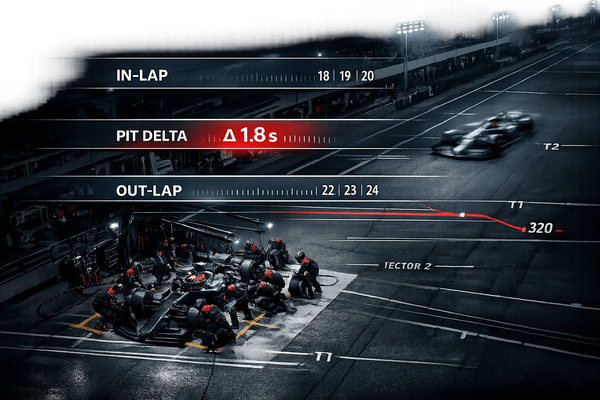

This controlled approach prevents wheel lock-up on the slippery surface. Drivers apply maximum pressure initially and then ease off as the car’s downforce reduces. Mercedes-AMG notes that while locking the wheels at high speeds above 185 mph (300 km/h) is rare, it becomes much easier at lower speeds - around 37 mph (60 km/h) - when downforce disappears.

Unlike road cars, Formula 1 vehicles lack Anti-lock Braking Systems (ABS), leaving drivers solely responsible for modulating brake pressure. They also fine-tune "brake migration" using steering wheel controls, dynamically adjusting the balance between the front and rear brakes to maintain stability. These fine adjustments help ensure a safer and more controlled entry into corners, which leads to changes in trail braking techniques.

Reducing Trail Braking in Wet Conditions

Trail braking - where drivers continue braking into a corner - becomes much riskier in the rain. Tires can’t manage both braking and turning forces at the same time on a wet track. To adapt, drivers use a "squaring off" technique: they brake deeper and wider before the corner, complete most of the braking in a straight line, and then take a sharper, slower turn. This approach allows them to straighten the car earlier on the exit and accelerate on sections of the track with better grip. As Cameron Ponsonby explains:

"Everything has to happen in straight lines. There simply isn't enough grip for sweeping side-to-side movements."

Another challenge is glazing, which can occur when brake temperatures drop too low. Light brake pressure - often used in trail braking - can polish the disc surface instead of creating friction, leading to a dangerous loss of braking power. McLaren’s Chief Race Engineer Hiroshi Imai elaborates:

"Glazing occurs when you have low temperatures in the braking system and use very light brake pressure. Rather than creating friction, the pads simply polish the surface of the disk."

Techniques for Avoiding Aquaplaning

Aquaplaning, where tires lose grip and glide over a layer of water, is a serious hazard in wet racing conditions. It’s not just about reacting when it happens - it’s about proactively preventing it. Drivers rely on smart track positioning and careful speed adjustments to stay in control and avoid this dangerous situation.

Following Tire Tracks for Better Grip

F1 tires are built to handle extreme conditions, with full wet tires capable of displacing up to 65 liters of water per second at maximum speed. But even with this impressive capability, drivers have an extra trick up their sleeves: following the tire tracks of the car ahead. These tracks have already been cleared of water, meaning the following car’s tires have less water to push aside, improving grip and reducing the risk of aquaplaning.

Scott Mansell, a professional driver, breaks it down:

"F1's big wide tires combined with the high speed as well as a low plank means that F1 cars are prone to aquaplaning... the best solution for a driver is to never aquaplane. To do this, they must avoid at all costs the puddles rivers and other standing water on the circuit. This is why you'll often see them following in each of those tire tracks when there's a lot of rain".

Drivers actively seek out these cleared paths, steering clear of puddles and "rivers" that form during heavy rain. When they do encounter standing water, they keep the steering wheel as straight as possible. This minimizes the risk of the car losing stability and skimming across the surface. This tactic pairs seamlessly with another critical adjustment: slowing down.

Slowing Down in Water-Heavy Areas

Reducing speed in waterlogged zones is one of the simplest yet most effective ways to avoid aquaplaning. While it may seem obvious, it’s a skill drivers must constantly refine, as standing water patterns shift unpredictably. Fernando Alonso highlights the challenge:

"In the wet, you have to improvise continuously... you will never have the same standing water on track [from one lap to next]".

Drivers must stay vigilant, scanning the track ahead and adjusting their speed before entering areas with heavy water. These careful speed reductions not only help prevent aquaplaning but also ensure they maintain control during braking, which is critical for navigating wet-weather races safely.

Visibility Problems and Braking Reference Points

Rain doesn’t just make the track slippery - it creates a wall of spray that can reduce visibility to almost nothing. When F1 cars hit high speeds in wet conditions, their tires and underfloor aerodynamics throw up massive amounts of water, forming a dense mist behind them. For drivers farther back in the pack, this means driving blind, unable to see the car ahead or even the track itself. Alongside adjusting braking techniques, dealing with impaired visibility becomes a key challenge for wet-weather racing.

Spray and Its Effect on Vision

Traveling at nearly 200 mph in heavy rain, visibility can drop to less than 164 feet (50 meters). The severity of the spray depends on the circuit. Open tracks like Silverstone allow the mist to disperse more quickly, while forested circuits such as Spa-Francorchamps trap the spray, leaving it hanging over the track like a thick fog.

This creates a dangerous paradox: drivers must maintain high speeds despite having almost no visibility. Slowing down too much risks being rear-ended by another car, whose driver is equally blind. To navigate this, drivers rely heavily on peripheral cues to judge braking points.

Using Trackside Markers for Braking Zones

When forward vision becomes unreliable, drivers shift their focus to static trackside markers to identify braking zones. These markers - visible in their peripheral vision - become essential. Former F1 driver Allan McNish explains:

"Peripheral vision becomes a driver's main line of sight, such as looking out for braking boards or marshal posts on the side of the road as a reminder of what's coming next".

Drivers look for specific cues like marshal posts, distance boards (e.g., 200m, 150m, 100m), the start of a curb, or changes in barrier colors - such as where Armco barriers switch shades. Scott Mansell highlights the importance of these markers:

"Spray can make it hard to see even 50m in front of you, so spotting braking points can sometimes be difficult. Your peripheral vision becomes increasingly important - a marshal's post, the start of a curb or the end of some Armco are all good examples".

During the first few laps of a wet session, drivers take note of these markers, creating a mental map they can rely on when visibility deteriorates.

Drivers Who Excel at Wet Weather Braking

Classic Wet Weather Performances

The best wet-weather drivers in F1 history share a rare ability: they find grip where others can't. Legends like Ayrton Senna and Michael Schumacher built their careers on this skill, often venturing off the traditional racing line to uncover better braking zones during rain-soaked races.

One of Senna's most iconic performances came at the Monaco Grand Prix in June 1984. Driving a less competitive Toleman, he used unconventional wet-weather lines and braking points to challenge for the lead before the race was ultimately stopped. By braking later and harder in unexpected areas, Senna pushed his car beyond its limits and cemented his place in F1 lore.

Similarly, Michael Schumacher's win at the Spanish Grand Prix in May 1996 is often cited as a masterclass in wet-weather driving. Battling torrential rain, Schumacher outperformed competitors in faster cars by relying on his exceptional feel for the brakes and an uncanny ability to find grip. Another standout moment in wet-weather history came from Gilles Villeneuve at the Canadian Grand Prix in October 1978. Racing in freezing 41°F temperatures with sleet and heavy rain, Villeneuve's precise braking control helped him secure victory in treacherous conditions.

These performances set the stage for modern drivers, who continue to refine and build on these techniques.

Recent Examples of Wet Braking Control

Today’s drivers have shown they’re capable of similar brilliance in the rain. Lewis Hamilton’s dominant display at the British Grand Prix at Silverstone in July 2008 is a prime example. In one of the most commanding wet-weather drives ever, Hamilton won by a staggering 68 seconds, maintaining grip and stability while many others struggled to stay on track.

Max Verstappen’s performance at the Brazilian Grand Prix in November 2016 was another showcase of wet-weather mastery. In torrential rain at Interlagos, Verstappen used unconventional racing lines and precise brake modulation to slice through the field, overtaking multiple cars even in standing water. Both Verstappen and Fernando Alonso are known for employing the "karting line", braking on the outer edges of corners where the asphalt is cleaner, and "squaring off" their exits to optimize traction.

Jenson Button also stands out for his unique approach to braking in wet conditions. McLaren’s Chief Race Engineer Hiroshi Imai once explained:

"Jenson does a lot of 'modulation' - continually adjusting the braking pressure after the initial peak braking. All drivers do it but Jenson is the most expert; the others are not up to his level".

This constant fine-tuning of brake pressure gave Button remarkable control, allowing him to maintain stability where others might lock up or lose traction.

Conclusion

Wet-weather braking is where F1 legends truly shine. While modern F1 cars are packed with cutting-edge technology, rain levels the playing field, shifting the spotlight entirely onto the driver's skill, instinct, and adaptability.

To excel in these conditions, drivers must make critical adjustments: braking earlier on cleaner sections of the track, applying pressure with precision to avoid locking up, and constantly adapting to the ever-changing grip levels. Without the assistance of ABS, every decision comes down to the driver’s own feel and judgment. Fernando Alonso summed it up best:

"In the wet, you have to improvise continuously. In the dry, you can have a very stable circuit for an hour and a half. But in wet conditions, you will never have the same standing water on track [from one lap to the next]".

Navigating a drenched circuit requires testing different racing lines, using peripheral vision to find markers when visibility is reduced by spray, and following tire tracks to reduce the risk of aquaplaning. Drivers who can master techniques like squaring off corners and "breathing off the pedals" gain a crucial edge. In the chaos of wet-weather racing, this ability to adapt and control the car becomes the ultimate test of a champion’s mettle.

FAQs

How do F1 drivers decide when to switch between wet and dry tires during a rainy race?

Switching between wet and dry tires in Formula 1 is a decision that hinges on precise teamwork between the driver, race engineer, and data analysts. Engineers keep a close eye on live weather radar, track temperatures, and lap times, while drivers share real-time insights about grip levels, braking stability, and visibility. When lap times drop significantly or traction diminishes, it's often a clear sign that slick tires are no longer suitable.

Wet tires are specially designed with grooves to channel water away and reduce the risk of aquaplaning, while slick tires excel on dry tracks. When standing water or slippery patches appear, teams weigh the time lost during a pit stop against the improved grip and performance wet tires provide. On the flip side, as the track dries and wet tires begin to overheat, engineers track lap-time gains to determine the right moment to switch back to slicks. The objective is always the same: maximize performance, ensure safety, and stay competitive.

How do F1 drivers prevent aquaplaning during heavy rain?

F1 drivers employ a variety of strategies to reduce the risk of aquaplaning when racing in wet conditions. One key adjustment involves tweaking their car's setup - raising the ride height and softening the suspension. This helps the car clear water more effectively and improves overall stability. Additionally, they increase the wing angles to boost downforce, ensuring the tires maintain better grip on the slick track.

On the circuit, drivers steer clear of the rubber-coated racing line, which turns dangerously slippery in the rain. Instead, they opt for cleaner, less-used sections of the track. To keep their tires firmly connected to the surface, they rely on gentle braking, smooth steering, and steady throttle control. These precise techniques help them manage water on the track and maintain control, even in tough weather conditions.

Why is braking in wet conditions so difficult for F1 drivers without ABS?

Braking on wet tracks is a real challenge because water dramatically reduces tire grip, particularly on the front tires, which bear the brunt of the steering load. When a driver hits the brakes, the car's weight shifts forward, putting extra pressure on the front wheels. On a slippery surface, this shift can easily push the tires beyond their grip threshold, causing them to lock up. Once the wheels lock, braking power and steering control are both compromised, making it much harder to slow down or navigate turns effectively.

In the absence of anti-lock braking systems (ABS), Formula 1 drivers must rely entirely on their own skill to fine-tune brake pressure and keep the wheels just shy of locking up. Wet weather adds another layer of difficulty, as grip levels can change unpredictably with water pooling on the track. To stay in control, drivers often apply gentle, steady brake pressure when entering corners to stabilize the car and prevent sudden lock-ups. However, even the slightest miscalculation can lead to longer stopping distances or even a spin. This makes braking in the rain one of the most demanding aspects of Formula 1 racing.