Energy Flow in MGU-H and Turbochargers

How F1’s MGU-H and turbochargers convert exhaust heat into electrical power, cut turbo lag, and reshape race energy strategy.

Modern Formula 1 cars use a 1.6-liter turbocharged V6 engine paired with hybrid systems like the MGU-H and MGU-K to balance power and efficiency. The MGU-H, directly connected to the turbocharger, recovers exhaust heat and converts it into electrical energy. This energy can be stored or sent to the MGU-K, which provides extra power to the engine. Turbochargers compress intake air to boost engine performance, while the MGU-H eliminates turbo lag and ensures consistent power delivery.

Key Highlights:

- MGU-H Function: Converts exhaust energy into electricity; eliminates turbo lag by spinning the turbocharger.

- Turbocharger Role: Compresses air for more oxygen in combustion, increasing engine power.

- Energy Flow: Exhaust energy → Turbine → MGU-H (electricity) → Battery or MGU-K → Engine.

- Efficiency: F1 engines achieve over 50% thermal efficiency, compared to ~35-40% in regular gas engines.

- FIA Regulations: MGU-K is capped at 120 kW power output and 4 MJ energy deployment per lap, while MGU-H has no energy limit.

These systems work together to maximize performance under strict fuel flow limits, making energy recovery and deployment critical to race strategies. However, starting in 2026, the MGU-H will be removed from F1 engines, requiring teams to find new ways to manage turbo lag and energy efficiency.

Power Unit 101 with PETRONAS: MGU-H, EXPLAINED!

How Energy Flows Between Components

The turbocharger–MGU-H system plays a key role in boosting performance by channeling energy efficiently. The process of converting exhaust energy into electrical power involves multiple steps, each with unique challenges and efficiency factors. Let’s break down how this energy moves through the system.

Exhaust Energy Path Through the System

When fuel ignites in the combustion chamber, hot exhaust gases exit the cylinders and flow into the manifold. Some heat escapes into the manifold walls and engine bay, reducing the energy available for further use. The remaining exhaust expands through the turbine, where a portion of its energy is converted into shaft power. This power drives the compressor and the MGU-H simultaneously.

The amount of recoverable energy depends on three factors: exhaust gas temperature, pressure ratio across the turbine, and mass flow rate. At high engine loads and RPMs - like when racing flat-out on a straightaway - hotter and faster exhaust gases generate the most shaft power. This benefits both the turbocharger and the MGU-H. On the other hand, during low RPMs or partial throttle, the reduced flow of exhaust limits energy recovery. In these scenarios, teams rely more on the MGU-H in motor mode to keep the turbo spinning.

However, not all energy is recoverable. Losses from turbine inefficiency, seal leakage, and residual heat reduce the total energy that can be captured. Even small improvements in turbine efficiency can translate into more electrical power for the MGU-K or battery.

MGU-H Generator and Motor Modes

After the turbine captures exhaust energy, the MGU-H operates in two modes: generator mode and motor mode.

In generator mode, the MGU-H converts shaft power into electrical energy. Control software carefully manages generator torque to balance energy recovery, turbo shaft speed (which can reach up to 125,000 RPM in current systems), and the compressor's torque needs. This ensures maximum energy recovery without risking turbo overspeed or loss of boost pressure.

In motor mode, the MGU-H provides electrical torque to accelerate the turbo shaft. This eliminates turbo lag by keeping the compressor spinning, even when exhaust energy is insufficient. For instance, when a driver exits a slow corner and accelerates, the MGU-H can deliver near-instant boost, improving lap times and drivability. However, this assist uses energy that could otherwise be directed toward propulsion.

The system switches between these modes based on real-time data, including turbo shaft speed, exhaust temperature, engine RPM, and driver input. The primary goal is to maintain optimal boost pressure while avoiding compressor surge. Any extra exhaust energy is then used for electrical generation.

Direct vs. Indirect Energy Transfer

Once the MGU-H generates electrical power, teams must decide whether to send it directly to the MGU-K or store it in the battery first. Each option has its pros and cons.

- Direct transfer from the MGU-H to the MGU-K is more efficient, with round-trip efficiency reaching the low 90% range. This approach avoids the energy losses associated with charging and discharging the battery. It also reduces thermal and cycling stress on the battery. However, it requires tight control of power flows and places additional mechanical stress on the turbo shaft and MGU-H components.

- Indirect transfer stores the energy in the battery before it’s sent to the MGU-K. While this method is slightly less efficient - dropping efficiency to the mid-80% range - it offers more flexibility. Teams can deploy stored energy strategically, smooth out power demands, and manage the battery’s state of charge within regulatory limits.

The choice between these methods depends on the track. High-speed circuits like Monza, with long full-throttle sections, favor direct transfer to keep the MGU-K close to its 120 kW output limit throughout the lap. In contrast, tighter tracks with frequent braking, such as Monaco, rely more on stored energy. Here, the MGU-H helps maintain turbo speed in slow corners, while the MGU-K deploys energy during short straights to enhance acceleration without causing wheelspin.

Strategic Importance of Energy Recovery

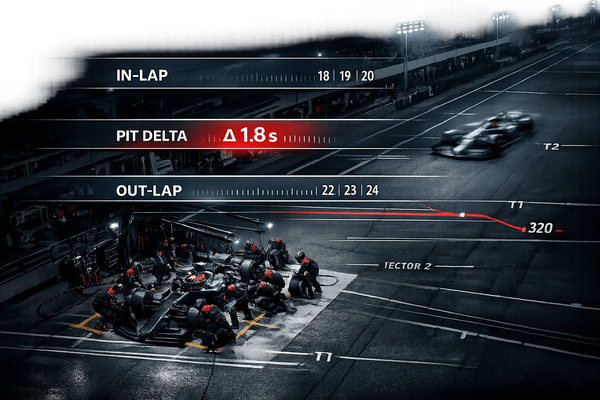

Track simulations reveal that MGU-K recovery opportunities vary widely by circuit. For example, high-braking tracks like Monaco enable up to 1.8 MJ of MGU-K recovery per lap, compared to around 1.2 MJ at low-braking tracks like Monza. This makes MGU-H recovery critical on power-sensitive circuits, where direct transfer is often preferred to sustain hybrid boost throughout the lap.

Under FIA regulations, the MGU-K is capped in both power (120 kW) and total energy deployment (4 MJ per lap). Meanwhile, the MGU-H can harvest and transfer unlimited energy, whether directly to the MGU-K or via the battery. Direct transfer from the MGU-H to the MGU-K can reduce energy cycling losses by up to 8 percentage points compared to routing energy through the battery.

For fans and engineers, these energy flows can be visualized using lap-time simulations and engine dyno data. Metrics like turbo shaft speed, exhaust temperature, manifold pressure, and electrical power flows between the MGU-H, battery, and MGU-K can be plotted to illustrate how energy is managed over a lap. Simplified models treat the exhaust-to-turbine-to-MGU-H path as an energy balance, factoring in fuel flow, thermal efficiency (around 50% for top F1 engines), and calibrated turbine/MGU-H efficiencies. These can be presented in Sankey diagrams or detailed energy budgets, such as those featured in technical resources like F1 Briefing.

Advanced MGU-H Technology

Manufacturers like Honda have developed MGU-H systems with compressors that perform efficiently across a wide range of pressure ratios and flow conditions. This design maximizes energy recovery under varying race conditions. By stabilizing turbo speed with electrical assistance, the MGU-H enables aggressive downsizing and higher boost levels, overcoming challenges like turbo lag and slow transient response.

Modern F1 V6 turbo-hybrid engines achieve peak brake thermal efficiency above 50%, thanks in large part to the combined efforts of MGU-H and MGU-K systems. Unlike the MGU-K, which is limited to 2 MJ of recovery and 4 MJ of deployment per lap, the MGU-H can recover exhaust energy without restriction under FIA rules. This makes it an essential tool for optimizing performance on the track.

Efficiency and Performance Optimization

Getting the most out of the MGU-H and turbocharger system requires a deep dive into where energy is lost, how software can fine-tune every watt, and how FIA regulations shape the overall strategy. A well-optimized system can shave off several tenths of a second per lap - a difference that can determine podium finishes.

Where Energy Losses Occur

Energy losses in F1 power units happen at multiple stages as exhaust gases are converted into electrical power. Understanding these losses highlights the complexity of modern systems.

The turbine in current F1 setups operates at 77.5% isentropic efficiency. This means around 22.5% of the exhaust energy is lost to heat, friction, and aerodynamic drag on the turbine blades - a remarkable achievement for a device spinning at over 100,000 RPM under extreme conditions.

Beyond the turbine, unrecovered exhaust gases, cooling systems, and friction also sap energy. Auxiliary components like oil and water pumps further reduce the available power. Even the compressor has efficiency challenges, especially when operating outside its optimal range, requiring extra shaft power to maintain boost pressure.

Despite these hurdles, Mercedes-AMG achieved 50% brake thermal efficiency with their 1.6-liter V6 turbo-hybrid engine. For comparison, everyday gasoline engines typically reach only 35–40%. This milestone reflects meticulous efforts to minimize energy loss across the system, from combustion chamber design to MGU-H integration.

Energy transfer efficiency also plays a critical role. Transferring energy from the MGU-H through the battery to the MGU-K achieves about 85% efficiency due to charge and discharge losses. On the other hand, directly transferring energy from the MGU-H to the MGU-K can reach nearly 93% efficiency. That 8% boost means more usable power from the same exhaust energy, less battery heat, and longer battery life.

| Energy Transfer Route | Effective Efficiency | Key Trade-offs |

|---|---|---|

| MGU-H → Battery → MGU-K | ~85% | Flexible timing for deployment but higher losses and battery stress |

| MGU-H → MGU-K (direct) | ~93% | Higher efficiency and reduced battery wear, but requires precise real-time power matching |

Even small improvements can have a big impact. For example, a 1% gain in turbine efficiency might add 0.3 kW of MGU-H power. Over a 190-mile (305 km) race, that extra power could translate into noticeable lap time reductions. With so many mechanical losses, advanced software is essential to recover and use every available watt effectively.

Software-Based Energy Management

The Engine Control Unit (ECU) acts as the brain of the hybrid system, making thousands of decisions per second to manage energy flow. While hardware determines the raw potential, software ensures that potential is turned into on-track performance.

The ECU tightly controls airflow and boost pressure, ensuring optimal fuel combustion. This precision allows the engine to operate right at the FIA-regulated fuel flow limit of 100 kg/h, extracting maximum power from every drop of fuel.

The system alternates between two main modes depending on the driving situation:

- Generator Mode: During high exhaust flow (like acceleration or high speeds), the MGU-H converts exhaust heat into electrical energy, which can either be stored or used immediately. The software balances factors like exhaust temperature, turbine speed, and compressor load to maximize energy recovery without losing boost pressure.

- Motor Mode: Under braking or low-speed acceleration, the MGU-H helps keep the turbo spinning, preventing turbo lag when exiting slow corners. The software predicts these needs based on throttle input, gear selection, and corner speeds.

At high speeds, the MGU-H can even regenerate more energy than the exhaust alone provides. This is achieved by carefully balancing turbine expansion, compressor workload, and electrical generation, ensuring that boost pressure remains consistent.

Track characteristics also influence software strategies. On high-speed circuits like Monza, where MGU-K recovery drops to around 1.2 MJ per lap, the software focuses on maximizing MGU-H recovery and direct energy transfer to the MGU-K during long straights. On braking-heavy tracks like Monaco, where MGU-K recovery can exceed 1.8 MJ per lap, the system leans more on MGU-H motor mode, relying on braking energy to recharge the battery.

The software also manages the battery's state of charge (SOC) across both individual laps and the entire race. Teams set SOC targets for specific track segments, ensuring enough capacity for MGU-K recovery during braking zones while maintaining reserves for straights. This predictive energy management balances immediate performance with long-term considerations like thermal limits and battery health, all within the strict boundaries of FIA regulations.

FIA Regulations and Energy Flow Limits

Every software strategy must comply with FIA's strict energy flow rules. These regulations create a complex framework that influences every decision related to energy management.

The most important restriction is the maximum fuel flow rate of 100 kg/h, which caps the total energy available from combustion. Teams also face a race fuel mass limit of 110 kg (around 242 lbs), requiring careful fuel management over the race.

The MGU-K is limited to 2 MJ of recovery per lap and 4 MJ of deployment per lap, with a peak power output of 120 kW (161 horsepower). These caps mean that energy recovered solely from braking isn’t enough to fully maximize hybrid performance over a lap.

In contrast, the MGU-H has no per-lap energy limit. Its output depends only on turbine and MGU-H efficiency, exhaust energy availability, and thermal capacity. FIA documentation even describes MGU-H energy as "free" since it doesn’t count against the MGU-K’s limits. This flexibility allows teams to strategically accept higher exhaust backpressure - reducing internal combustion engine power - to capture more energy via the MGU-H, which can then be deployed without affecting MGU-K restrictions.

These rules, while restrictive in some areas, provide opportunities for clever energy management and optimization, keeping the competition dynamic and rewarding precision engineering.

Turbocharger and MGU-H Hardware Design

The design of the turbocharger and MGU-H plays a critical role in capturing exhaust energy and ensuring quick response times. Decisions around hardware - such as turbine and compressor sizes or bearing types - require a careful balance between maximizing power output, maintaining reliability, and optimizing energy recovery. These choices directly influence how the system integrates and how effectively it can be calibrated.

Turbocharger Sizing and Performance

When it comes to turbocharger performance, key factors like turbine and compressor wheel diameters, the turbine housing A/R ratio, and maximum shaft speed determine how much exhaust energy can be converted into electrical power and how quickly boost pressure is delivered. Larger wheels and tighter A/R ratios can capture more energy but also introduce more inertia. This added inertia can slow down boost response and increase exhaust backpressure, potentially impacting engine efficiency and reliability over the course of a long 190-mile race.

Engineers face a tricky balancing act here. An oversized turbine can capture more energy but may hurt throttle response, while an undersized one spools up faster but leaves some exhaust energy untapped. Current designs aim to match efficiency benchmarks.

Formula 1 turbochargers operate at speeds exceeding 100,000 RPM, pushing materials and bearings to their limits. To prevent failures - such as bearing breakdowns, turbine blade creep, or generator overheating - engineers cap turbine inlet temperatures and shaft speeds below maximum thresholds. This approach sacrifices a small fraction of peak power but reduces risks of race-ending issues or penalties from unscheduled power unit changes.

Honda's advancements highlight these challenges. For example, their 2020 RA620H incorporated three-dimensional turbine blade designs to improve efficiency. The following year, the RA621H introduced better energy recovery at lower engine speeds, aided by improved torque delivery - an area where Honda leveraged expertise from their HondaJet gas-turbine program. Additionally, their 2019 French Grand Prix compressor design extended the range of pressure ratios and airflow rates, ensuring consistent energy recovery across varying race conditions.

Engineering Challenges and Solutions

Integrating the MGU-H into the turbocharger system comes with its own set of difficulties. Adding this high-speed electrical machine to an already fast-spinning turbo shaft increases mass and creates additional electromagnetic forces. These factors can lead to rotor dynamics issues like critical speeds, shaft whirling, and higher bearing loads. Engineers address these problems through precision shaft designs, advanced bearing systems with optimized oil film management, and strategic placement of the MGU-H rotor to minimize vibration and fatigue. Even minor imbalances at such high speeds can have catastrophic consequences.

Thermal management is another major hurdle. Exhaust temperatures often exceed 1,800°F (982°C), requiring advanced materials that can withstand extreme heat while resisting creep and oxidation during long races. These materials help maximize energy recovery without compromising structural integrity.

The MGU-H itself relies on specialized cooling strategies. Honda, for instance, used high magnetic flux density magnets and thermally efficient insulators to improve cooling and output. Dedicated oil circuits, additional cooling paths for the stator and rotor, and heat shielding between the turbine and compressor work together to prevent overheating and oil degradation during a race.

Recent innovations, such as longer turbo shafts and aerodynamically optimized turbine and compressor blades, have further improved efficiency. These upgrades allow more exhaust energy to be converted into rotational power for the MGU-H while minimizing backpressure. Layout adjustments, like repositioning components, can also improve packaging, though they may slightly increase assembly weight and complicate shaft design.

To validate these hardware decisions, teams rely heavily on telemetry data. By monitoring parameters like turbo shaft speed, turbine inlet and outlet temperatures, compressor pressure, MGU-H torque, and fuel flow, engineers can ensure the system performs as expected. Comparing this real-world data with simulations helps identify potential issues, such as excessive backpressure or insufficient energy recovery, enabling teams to fine-tune control maps before critical qualifying sessions or races.

Comparing Different Turbocharger–MGU-H Setups

Once the engineering challenges are addressed, teams differentiate their systems through distinct design approaches. Some teams favor high-boost, high-speed setups to maximize energy recovery and peak performance. These configurations can deliver higher electrical output and more aggressive boost but require intricate calibration, tighter reliability margins, and advanced cooling systems.

Other teams opt for more conservative setups, prioritizing durability and easier calibration across multiple race weekends. While these systems may forgo a few kilowatts of peak power, they offer longer component life and more forgiving operating conditions. Calibration engineers develop detailed maps to balance energy harvesting and motor mode torque. For qualifying, the system is tuned for rapid boost and maximum energy deployment to the MGU-K, while during races, it focuses on fuel efficiency and combustion stability.

The MGU-H must also meet regulatory requirements, including a minimum weight of 4 kilograms with no upper limit. This flexibility allows teams to optimize energy extraction, though any added mass must be carefully managed to avoid increased rotor-dynamic loads and vibration issues.

Race Day Applications and Team Decisions

On race day, all the intricate hardware refinements come into play as teams make split-second decisions about how to manage energy across the turbocharger, MGU-H, battery, and MGU-K. These decisions, often pre-programmed into engine modes, have a direct impact on lap times, overtaking opportunities, fuel efficiency, and whether a car has enough energy left for a late-race push or to defend its position. This dynamic energy management strategy is built on the foundation of prior hardware and software tuning.

The unique layout of each circuit dictates how teams prioritize energy flow. For instance, high-speed tracks like Monza or Spa, with their long straights and limited heavy braking zones, present a challenge. On these tracks, the MGU-K typically recovers only about 1.2 MJ per lap, far below its regulatory limit, due to fewer braking opportunities. In such cases, the MGU-H takes on a critical role by converting exhaust energy into usable power. Teams configure the system to send more energy directly from the MGU-H to the MGU-K, maximizing straight-line speed. This approach allows the battery to operate with a leaner charge, as the high exhaust flow consistently replenishes energy during the race.

In contrast, technical or street circuits like Monaco or Singapore tell a different story. With frequent braking zones, the MGU-K can recover nearly 1.8 MJ per lap, approaching its maximum limit. Here, the MGU-H focuses more on maintaining turbo speed and reducing turbo lag, especially during low-speed corner exits. Since exhaust flow is less consistent on these circuits, the battery retains a healthier charge to ensure smoother energy deployment. The goal shifts from outright power to ensuring consistent drivability and efficient operation during the many short bursts of acceleration.

| Circuit Type | Typical MGU-K Recovery | MGU-H Priority | Energy Deployment Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-speed (few braking zones) | ~1.2 MJ per lap | Higher; supplements limited MGU-K recovery | Maximizing straight-line speed via direct MGU-H to MGU-K transfer |

| Technical/street (many braking zones) | ~1.8 MJ per lap | Moderate; supports drivability and lag reduction | Corner-exit traction and short-burst deployment for overtakes |

Adjusting Energy Use During Races

Teams continuously tweak energy flows during the race to adapt to the circuit's demands. Engineers monitor real-time data, including turbocharger speed, exhaust pressure, battery charge levels, and fuel flow. These inputs feed into predictive control systems that determine how the MGU-H should operate - whether to harvest energy for the battery, send power directly to the MGU-K, or act as a motor to reduce turbo lag.

During attack phases, the focus is on maximum power. The MGU-H may feed energy straight to the MGU-K or support aggressive battery discharge, even if it means accepting slightly higher exhaust backpressure. This approach can shave tenths of a second off lap times in critical sections like straights or DRS zones. Conversely, in defense or fuel-saving phases, teams prioritize energy harvesting, with the MGU-H channeling power into the battery while maintaining competitive speed with reduced fuel consumption. Mismanaging this balance can cost several tenths per lap, which can make or break a race outcome over a full distance.

Strategic energy deployment also plays a key role in undercut and overcut strategies. For an undercut, teams often program a short burst of intense energy use during the in-lap and out-lap to maximize tire performance and gain track position. For an overcut, the focus is on consistent lap times, preserving tires and fuel, and saving energy for a decisive push when the car is in clear air with lighter fuel loads.

Real Race Examples of Energy Flow Decisions

Real-world examples highlight how energy flow strategies can shape race outcomes. Teams with efficient MGU-H systems often maintain richer deployment modes for longer, allowing them to sustain overtakes or defend effectively on power-sensitive tracks. By optimizing energy recovery during high exhaust flow conditions and carefully managing turbo speed and backpressure, these teams achieve competitive lap times without compromising fuel efficiency or thermal limits.

In other cases, a conservative strategy early in the race has proven beneficial. Teams focusing on fuel-saving measures and using the MGU-H to maintain turbo boost with reduced fuel flow often finish with reserves of both energy and fuel. This allows for late-race surges or strategic undercuts, gaining positions when rivals with less efficient systems are forced to scale back power to manage fuel or temperature issues. Sometimes, the difference between a podium finish and a mid-pack result comes down to being able to deploy an extra 10–20 kW (13–27 hp) of MGU-H power during the final laps without exceeding fuel caps or risking overheating.

To craft these circuit-specific strategies, teams rely on advanced lap simulations. These simulations integrate detailed power unit models, efficiency maps, tire degradation data, and traffic scenarios to predict how different energy deployment strategies will affect lap times, fuel usage, and thermal loads over a race. The results guide decisions on energy budgets, sector-specific deployment windows, and acceptable battery charge levels, which are then encoded into engine modes like attack, defense, or fuel-save. Drivers and engineers can then select these modes with confidence during the race.

For fans diving deeper into race strategy on platforms like F1 Briefing (https://f1briefing.com), understanding these energy flow decisions adds a fascinating layer to race analysis. Visuals like corner-by-corner deployment maps, battery charge traces, and MGU-H power curves (in both horsepower and kilowatts) highlight how teams approach energy management differently. Pairing this data with insights from engineers and drivers about how the car felt in attack versus defense phases brings these strategies to life, showing how hybrid systems and energy management directly influence on-track battles and race results.

Conclusion and Future Impact

Main Findings on Energy Flow

The MGU-H and turbocharger system represent a standout example of energy recovery in motorsport. By converting exhaust heat into electrical energy, this system provides a dual benefit: it can either deliver an extra 160 horsepower to the MGU-K for immediate use or charge the battery for later deployment. This setup achieves an impressive 50% thermal efficiency, a critical factor in modern F1 power units. Teams must carefully balance how they allocate this energy - whether to drive the compressor, charge the battery, or power the MGU-K - depending on race conditions.

For fans in the U.S., the practical impact of these efficiency gains is clear. On high-speed circuits like Monza or Spa, where power output is crucial, effective energy recovery can cut several tenths of a second from lap times. With strict fuel flow limits in place, this technology essentially allows teams to put more power to the wheels without burning additional fuel.

However, this comes with trade-offs. Harvesting more energy through the MGU-H increases exhaust backpressure, which can restrict engine breathing and slow throttle response, particularly when exiting corners. Additional losses arise from turbine and compressor inefficiencies, heat dissipation, and electrical conversion. FIA regulations also cap how much energy can be deployed per lap. To mitigate these challenges, teams use advanced software to dynamically adjust turbo speed, harvesting rates, and deployment timing based on changing race conditions. These strategies lay the groundwork for the next evolution in hybrid power units.

Changes to Hybrid Power Units After 2025

Looking ahead, the 2026 regulation changes will bring a major shift in F1’s energy systems. The MGU-H will no longer be part of the power units, marking the end of an era. Without the MGU-H, teams lose the ability to harvest exhaust heat or control turbo speed to counteract turbo lag. As a result, turbo lag is expected to return, especially during low exhaust flow or after extended off-throttle periods.

This change disrupts the integrated energy management strategies perfected during the MGU-H era, forcing teams to adapt. The focus will shift to a more robust MGU-K, improved energy recovery from braking, and tighter restrictions on electrical power. Teams will need to prioritize battery capacity, braking stability, and advanced deployment strategies to maintain competitive performance. Engine manufacturers will also need to rethink turbocharger and combustion system designs to compensate for the lack of MGU-H control. Potential solutions might include more aggressive boost management, anti-lag combustion techniques, or redesigned turbines to maintain turbo speed.

For U.S. fans who follow high-performance turbocharged road cars, this transition may feel familiar. Techniques like smaller, faster-spooling turbos or twin-scroll designs - common in aftermarket tuning - could influence how F1 teams address turbo lag in the post-MGU-H era. Teams that excelled with holistic energy strategies during the MGU-H years will now need to redirect their focus toward improving combustion efficiency, battery systems, and turbo responsiveness.

Waste Heat Recovery in Road Cars

The innovations seen in F1 are already influencing road-car technology. The MGU-H, essentially a high-speed waste-heat recovery system, has inspired similar developments for passenger and commercial vehicles. Concepts like turbo-compounding, electric turbochargers, and thermoelectric systems aim to reclaim exhaust energy, boosting fuel efficiency and reducing emissions. Even modest efficiency improvements can make a big difference for everyday vehicles, lowering fuel costs and environmental impact.

For example, Honda’s work on the MGU-H, which drew from their expertise in jet engine design, highlights how motorsport innovation can trickle down to road-car engineering. Slight gains in thermal efficiency can lead to substantial fuel savings for commercial fleets and heavy-duty vehicles. While the complexity and cost of F1-style MGU-H systems limit their use in mass-market cars, scaled-down versions are already shaping the future of turbocharger and hybrid engine designs.

Research is now focused on advanced turbo-machinery, high-speed electric systems, and materials that can handle higher exhaust temperatures and rotational speeds without sacrificing reliability. Emerging technologies, like fully electric turbochargers and integrated starter-generators, promise even greater efficiency improvements. For those interested in a deeper dive into these advancements, F1 Briefing offers detailed coverage of power-unit architecture, race strategies, and regulatory updates. These developments show how F1’s energy recovery systems continue to push boundaries, driving progress both on the track and in the vehicles we see on the road.

FAQs

How will removing the MGU-H in 2026 impact F1 team performance and strategies?

The removal of the MGU-H (Motor Generator Unit - Heat) in 2026 is set to shake up how F1 teams approach both engine performance and race strategies. The MGU-H, which currently recovers energy from exhaust gases to enhance efficiency and power delivery, plays a crucial role in modern Formula 1 engines. Without it, teams will need to rethink their reliance on other hybrid components and refine engine designs to stay competitive.

This shift is likely to put a greater spotlight on turbocharger efficiency and the use of systems like the MGU-K (Motor Generator Unit - Kinetic) for energy recovery. It could also open the door to more intricate energy management strategies during races as teams work around the absence of this advanced technology. While the change presents challenges, it also aligns with F1's ongoing goals of promoting sustainability and controlling costs, potentially driving fresh engineering solutions in the process.

How do energy transfer methods differ between the MGU-H and MGU-K systems?

The MGU-H (Motor Generator Unit-Heat) and MGU-K (Motor Generator Unit-Kinetic) play distinct roles in managing energy within an F1 car, each targeting a different source of energy. The MGU-H captures heat energy from the turbocharger's exhaust gases and converts it into electrical energy. This energy can either be stored in the car's battery, used to power the MGU-K, or assist the turbocharger directly.

On the other hand, the MGU-K focuses on recovering kinetic energy generated during braking. It transforms this energy into electrical power, which can then be stored or used immediately.

The primary difference between the two lies in where they draw their energy: the MGU-H utilizes exhaust gases, while the MGU-K relies on braking forces. Working together, these systems boost energy efficiency and performance, enabling F1 cars to deliver maximum power while staying within strict energy regulations.

How do F1 teams decide between using the MGU-H in generator mode or motor mode during a race?

F1 teams decide whether to operate the MGU-H in generator mode or motor mode by weighing factors like energy efficiency, race strategy, and real-time performance data.

When in generator mode, the MGU-H captures excess energy from the turbocharger, converting it into electrical energy. This energy can either be stored in the car's battery or used to power the MGU-K. Teams typically lean on this mode when energy recovery is essential to sustain competitive performance throughout the race.

In contrast, motor mode focuses on minimizing turbo lag. It uses stored electrical energy to keep the turbocharger spinning, ensuring the engine responds quickly during acceleration. This can be a game-changer in situations that demand sharp throttle responses.

The choice between these modes often hinges on factors like the track's characteristics, weather conditions, and the team's overall energy management approach. For instance, circuits with long straights might see teams prioritizing generator mode to recover as much energy as possible. Meanwhile, on tracks with frequent acceleration zones, motor mode could provide a performance edge by enhancing throttle responsiveness.