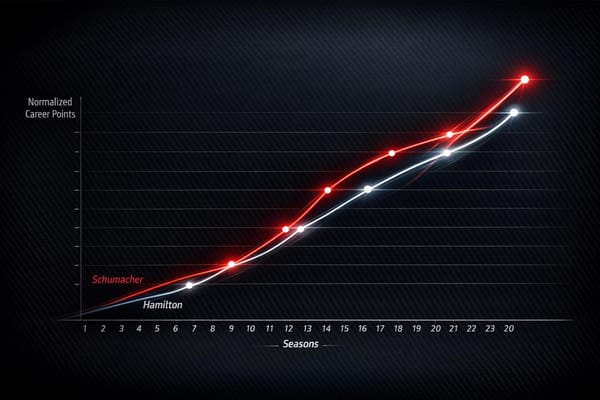

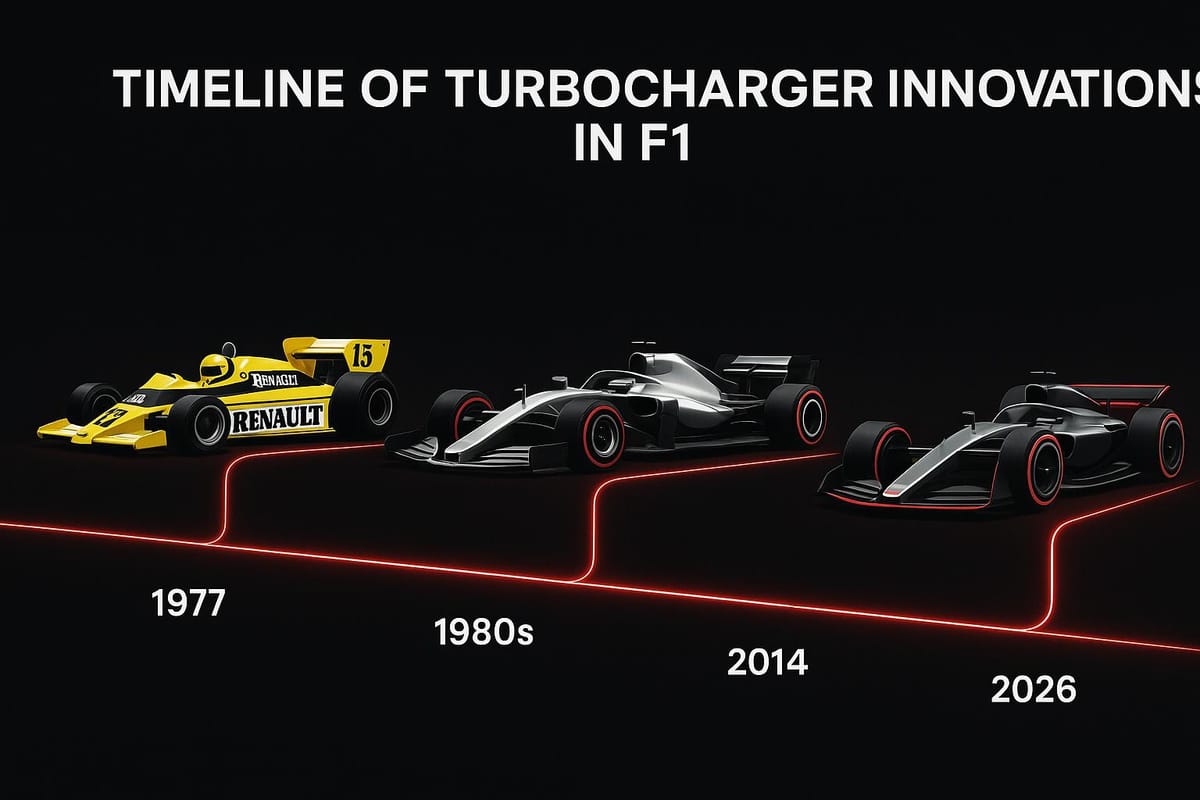

Timeline of Turbocharger Innovations in F1

A timeline of turbocharger innovation in Formula One — Renault’s 1977 breakthrough, the 1980s power peak, the 1989 ban, the 2014 hybrid return, and 2026 changes.

Turbochargers have reshaped Formula One, boosting engine performance and changing the sport's competitive landscape. From Renault's bold RS01 debut in 1977 to today's hybrid power units, this technology has driven F1's evolution. Here's a quick overview:

- 1970s: Renault introduced turbocharging in F1, overcoming early reliability issues.

- 1980s: Turbo dominance peaked, with engines exceeding 1,300 horsepower but raising safety and cost concerns.

- 1989: Turbochargers were banned, shifting F1 to naturally aspirated engines.

- 2014: Turbocharging returned with hybrid systems, emphasizing efficiency and energy recovery.

- 2026: Upcoming regulations will refine hybrid turbos, focusing on sustainable fuels and simplified systems.

Turbochargers have not only increased power but also inspired engineering advancements, balancing performance with modern priorities.

THE WORLD'S FASTEST GRENADES! The Story of F1's Turbo Era (1977-1988)

Pre-Turbo Era and Early Experiments (1950s–1976)

In the early days of Formula One, teams leaned toward using superchargers rather than experimenting with turbochargers. This preference reflected both the limits of available technology and the cautious approach of racing teams during that time.

Superchargers vs. Turbos in the 1950s

During the 1950s, superchargers were the go-to technology for forced induction in Formula One. These systems, driven mechanically by a belt connected to the engine's crankshaft, compressed air to deliver immediate and reliable power. Teams favored superchargers because they were simple, dependable, and had a proven track record in racing.

Turbochargers, although invented as early as 1905 by Swiss engineer Alfred Büchi, were largely overlooked in F1. While they had been successfully used in large diesel engines in the 1920s and even in some commercial cars by 1938, F1 teams hesitated to adopt them for racing purposes.

The reasons were clear. Superchargers offered instant power without the lag associated with early turbo systems. When a driver hit the throttle, a supercharged engine responded immediately. Turbocharged engines, however, needed time for exhaust gases to spool up the turbine, causing a delay that could make the car harder to handle during critical moments on the track.

Additionally, superchargers were mechanically straightforward. Their belt-driven design involved fewer moving parts exposed to extreme stress, such as high temperatures and rapid speeds. Turbo systems, by contrast, relied on turbine wheels that spun at incredibly high RPM while enduring the intense heat of exhaust gases, making them prone to reliability issues. For teams focused on performance and consistency, the risks and complexities of turbochargers outweighed their potential benefits. This conservative stance shaped the early decades of F1's approach to engine technology.

The Gap Years (1960s–1976)

The 1960s through 1976 marked a curious period in F1's technological evolution. While turbocharging advanced in other areas of the automotive world, Formula One teams continued to steer clear of it. Even when the FIA allowed turbochargers starting in 1976, no team rushed to adopt the technology.

Regulations played a big role in this reluctance. During the early 1970s, F1 rules limited engines to 3 liters of displacement with naturally aspirated induction, favoring 12-cylinder engines that delivered around 500 horsepower. Teams had spent years refining these engines, and the performance was well understood. When the FIA eventually permitted forced induction while maintaining the 3-liter displacement limit, it opened the door for turbo technology. But teams remained hesitant due to ongoing concerns about reliability and performance.

Early turbo engines had significant drawbacks. They were slow to respond and prone to failures under the extreme conditions of racing. Developing a reliable turbo system required extensive research, advanced cooling solutions, and materials capable of withstanding both high temperatures and immense stress. Effective boost management was another hurdle that added to the complexity. These challenges made turbocharging an expensive and risky endeavor, discouraging teams from pursuing it. At this stage, the technology needed a breakthrough to prove its worth in the fiercely competitive world of Formula One.

Renault's Turbo Breakthrough (1977–1980)

In the late 1970s, while most Formula One teams hesitated to embrace turbocharging, Renault decided to push the boundaries. After spending a decade on research and development, the French manufacturer convinced the FIA to allow turbocharged engines starting in 1976. This groundbreaking regulatory change opened the door to a new era of F1 powertrains and set the stage for Renault's bold experiment: the RS01.

Renault RS01: The First Turbocharged F1 Car

Renault made history in 1977 when it introduced the RS01, the first turbocharged car in Formula One. Designed by François Castaing, the RS01 generated over 500 horsepower. However, it was far from perfect. The car struggled with severe turbo lag and frequent mechanical failures, especially at low RPM. These issues led many in the F1 world to doubt whether turbocharging could ever succeed in such a demanding environment.

To address these growing pains, the FIA imposed a boost pressure limit of 1.5 bar, aiming to protect the engines while the technology advanced. Despite the challenges and restrictions, Renault remained committed to proving that turbocharged engines could revolutionize the sport. This determination marked a pivotal moment in F1's technological evolution.

First Turbo Victory: Dijon 1979

Renault's persistence paid off in 1979 at the Dijon Grand Prix, where the team secured the first-ever Formula One victory for a turbocharged car. This win was a game-changer. It silenced skeptics and showcased the potential of turbo engines, proving they could be refined to deliver consistent, race-winning performance.

By 1980, Renault had demonstrated that turbocharging wasn't just viable - it was essential, particularly at high-altitude circuits like Kyalami and Interlagos. At these tracks, naturally aspirated engines struggled due to thinner air, while turbocharged engines maintained their power by forcing more air into the combustion chamber. This advantage highlighted the versatility and potential of turbo technology.

Renault's success sparked a turbo revolution in Formula One, prompting other teams to adopt the technology and fundamentally altering the landscape of engine design. The era of turbocharged dominance had begun, reshaping the sport's power dynamics forever.

Peak Turbo Power and Dominance (1981–1986)

The period from 1981 to 1986 saw turbocharged engines take center stage in Formula One, transforming the sport in just a few years. Renault’s groundbreaking victory at Dijon in 1979 had set the stage, but by the early '80s, turbo technology had become a necessity for any team aiming to stay competitive. This rapid evolution forced teams to adapt quickly, ushering in a new era of power and speed.

Top Teams Embrace Turbocharging

The turbocharged revolution gained momentum as top teams began adopting the technology. Ferrari was among the first to follow Renault's lead, introducing its V6 turbocharged engine in 1981. Around the same time, Brabham, under Bernie Ecclestone’s leadership, joined forces with BMW to develop a straight-4 turbo engine. This collaboration proved to be a game-changer, powering Nelson Piquet to championship victories in 1981 and 1983. The compact 1.5-liter BMW engine was a marvel, reportedly delivering an astonishing 1,300 horsepower during qualifying sessions.

By 1983, the turbo era was in full swing. Alfa Romeo entered the fray with a V8 turbo engine, while Honda and Porsche (the latter branded as TAG thanks to its financial backer) unveiled their own V6 turbocharged designs. Other manufacturers, including Cosworth, Motori Moderni, and Hart Racing Engines, also joined the turbo movement, each contributing unique designs to the grid.

The competitive landscape shifted dramatically. By mid-1985, every car on the Formula One grid was turbocharged. Teams without access to cutting-edge turbo systems struggled to keep up, often resorting to building their own engines or partnering with established manufacturers. Engines like BMW's straight-4 turbo and the McLaren-TAG Porsche V6 became dominant forces, driving championship wins for drivers like Piquet, Niki Lauda, and Alain Prost. Success in this era required more than just raw horsepower - reliability and advanced engine management were equally critical.

Unleashing Over 1,000 Horsepower

As turbo engines became the norm, the focus shifted to managing the immense power they could produce. By 1986, turbocharged engines regularly exceeded 1,000 horsepower (750 kilowatts) in qualifying sessions, thanks to unrestricted boost pressures. Some manufacturers pushed even further, with 1.5-liter V6 engines delivering over 1,300 horsepower in race trim and qualifying power peaking between 1,400 and 1,500 PS (around 1,100 kilowatts). This represented a staggering leap in performance, with power outputs nearly tripling in just over a decade.

Turbocharged engines also thrived at high-altitude circuits like Kyalami in South Africa and Interlagos in Brazil. Unlike naturally aspirated engines, which struggled with reduced air density, turbo engines maintained their performance, giving them a distinct advantage.

Qualifying sessions became spectacles of sheer power, with teams running engines at maximum boost levels, fully aware they might need to replace them afterward. Race-day setups were more conservative, prioritizing durability over outright speed. Even then, the "detuned" engines produced power levels that would have been unimaginable just a few years earlier.

Overcoming Turbo Era Challenges

While turbocharged engines delivered breathtaking power, they brought their share of challenges. Extreme boost pressures and high combustion temperatures pushed engineering to its limits, requiring advanced systems to manage these forces effectively.

Fuel consumption was another major hurdle. High boost settings consumed enormous amounts of fuel, prompting the FIA to impose stricter fuel limits. Teams had to carefully manage boost pressure throughout races, developing strategies that balanced speed with efficiency. Engineers and drivers worked closely to optimize fuel use, especially during longer races where running out of fuel could spell disaster, no matter how fast the car.

The diversity of engine designs during this period highlighted the various approaches teams took to these challenges. BMW’s straight-4, Ferrari’s V6, Honda’s V6, Porsche’s TAG-badged V6, and Alfa Romeo’s V8 all showcased different philosophies in tackling turbo technology. However, one thing was clear: reliability became just as important as raw power. Manufacturers raced to produce engines that could not only perform at the highest level but also endure the grueling demands of an entire race distance. Turbocharging had changed the game, and only those who mastered its complexities could hope to dominate.

Regulations and the End of the Turbo Era (1987–1988)

By the mid-1980s, Formula 1 had reached new extremes, with turbocharged engines delivering over 1,300 horsepower. While this raw power thrilled fans, it also led to soaring costs and growing safety concerns. In response, the FIA launched a two-year plan to overhaul the sport’s technical rules, reshaping its future.

Boost Pressure Limits and New Constraints

In 1987, the FIA took a significant step by capping turbo boost pressure at 4 bar during qualifying and reducing fuel tank capacity to 150 liters. The following year, the boost limit was tightened further to 2.5 bar. These changes forced teams to carefully manage fuel consumption, making sustained high-boost performance nearly impossible. At the same time, the FIA allowed teams to use 3.5-liter naturally aspirated engines alongside the restricted turbos, signaling the beginning of the end for the turbo era.

Despite these restrictions, turbocharged engines remained formidable. Honda’s RA168E V6 turbo, for instance, could still produce 685 horsepower at 12,300 rpm in qualifying trim, far outpacing naturally aspirated engines like the Ford-Cosworth DFZ, which managed 575 horsepower. However, only six teams - McLaren, Ferrari, Lotus, Arrows, Osella, and Zakspeed - continued to field turbo engines. Among them, McLaren's partnership with Honda stood out, as their MP4/4 car dominated the 1988 season, winning 15 out of 16 races.

The regulatory changes also posed significant technical challenges. Teams had to recalibrate nearly every aspect of their turbo setups - adjusting turbo sizing, fuel mapping, ignition timing, and intercooler efficiency. While manufacturers like Honda and Ferrari, who had heavily invested in turbo technology, managed to stay competitive, others struggled to keep up. These shifts in the rules marked a turning point, pushing teams toward naturally aspirated engines.

The Shift to Naturally Aspirated Engines

To guide the sport through this transition, the FIA introduced a dual-engine formula in 1987. Teams could choose between the restricted turbo engines or the new 3.5-liter naturally aspirated alternatives. This flexibility allowed manufacturers to align their strategies with their technical expertise and resources. However, as the turbo regulations grew tighter, even established turbo powerhouses like Ferrari, BMW, and Honda began rethinking their focus, gradually shifting their efforts toward naturally aspirated engines.

The turbo era officially ended with a complete ban on turbocharged engines for the 1989 season, closing a chapter that had begun with Renault’s pioneering turbo debut in 1977.

This shift brought a dramatic change to Formula 1’s engine landscape. Teams transitioned from compact, high-boost 1.5-liter turbos to larger, naturally aspirated engines designed to operate at higher RPMs. For instance, Honda’s RA109E V10 produced 685 horsepower at 13,500 rpm, while Ferrari’s new Tipo 037 engine reached 710 horsepower at 13,800 rpm. These changes leveled the playing field and set the stage for two decades of naturally aspirated dominance, a trend that lasted until turbocharged engines returned in a hybrid format in 2014.

Hybrid-Era Turbochargers (2014–Present)

After a 25-year run with naturally aspirated engines, Formula 1 reintroduced turbocharged power in 2014. But this wasn’t just a nostalgic return to the turbocharged dominance of the 1980s. This time, the emphasis shifted significantly - from raw horsepower to a focus on efficiency and environmental considerations. The hybrid power units that debuted in 2014 combined turbocharged engines with cutting-edge energy recovery systems, setting the stage for a new performance philosophy. These changes, driven by updated regulations, completely reshaped the sport's technological landscape.

Introduction of Hybrid Turbo Power Units

The 2014 season ushered in a new era of F1 technology. The FIA replaced the 2.4-liter naturally aspirated V8 engines, which had been standard since 2006, with 1.6-liter V6 turbocharged engines capped at 15,000 rpm. Unlike the earlier turbo era, where teams cranked up boost pressures to chase raw speed, the new rules prioritized fuel efficiency and emission reductions.

A groundbreaking feature of these power units was the integration of two energy recovery systems: the MGU-K (Motor Generator Unit-Kinetic), which harvests energy during braking, and the MGU-H (Motor Generator Unit-Heat), which recovers thermal energy from exhaust gases. These systems work in tandem with the turbocharged engine, transforming wasted energy into additional power.

This shift required teams to master entirely new technical challenges. They had to navigate the complexities of battery storage, energy deployment strategies, and turbo calibration. Mercedes quickly established itself as a dominant force, with Lewis Hamilton capturing championships in both 2014 and 2015 using their advanced hybrid turbo systems. Ferrari also made significant strides, becoming a key player in the development of hybrid turbo technology.

Efficiency and Performance in Modern Turbos

Modern F1 turbocharged engines are engineering marvels, delivering around 900 horsepower from the internal combustion engine alone. When paired with the energy recovery systems, total output climbs to nearly 1,000 horsepower. This level of performance is achieved while adhering to strict fuel flow limits, which force teams to prioritize efficiency over brute force.

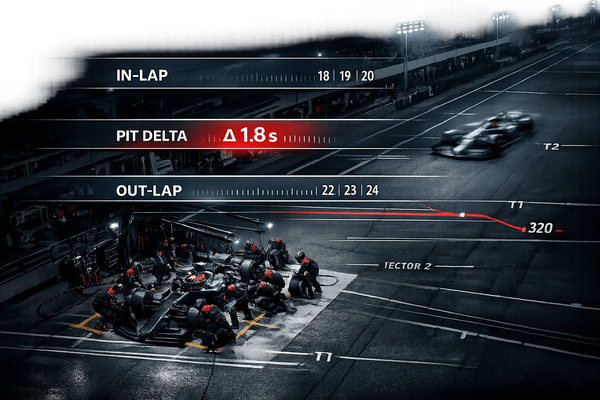

Rather than relying on short bursts of extreme boost pressure, engineers now focus on optimizing combustion efficiency and energy recovery throughout an entire race. Additionally, with teams limited to just five engines per season, reliability has become just as important as performance.

Advanced engine management systems play a crucial role in this era. These systems constantly adjust turbo settings, fuel mapping, and energy deployment based on track conditions and race strategies. Drivers can strategically use stored energy during key moments of a race, adding a layer of tactical complexity that didn’t exist in the naturally aspirated era. This efficiency-driven approach not only enhances competition but also aligns with broader environmental objectives.

The environmental impact of these changes has been substantial. The smaller, more efficient engines consume significantly less fuel than the old V8s while maintaining competitive lap times. Energy recovery systems capture and reuse power that would otherwise be wasted, further boosting efficiency. As a result, F1 has become a proving ground for hybrid technologies that could eventually find their way into everyday road cars, supporting global sustainability goals.

Technical Progress in the Hybrid Era

Since 2014, F1's hybrid turbo systems have seen continuous improvement, with manufacturers pushing the boundaries of efficiency, performance, and durability. The MGU-H, in particular, has revolutionized turbocharger functionality. By actively managing boost pressure, it eliminates the lag that plagued earlier turbo designs, ensuring seamless power delivery.

The integration of energy recovery systems has driven advancements in materials science and precision engineering. Modern turbochargers must meet the demanding requirements of hybrid power units while remaining reliable over multiple race weekends. Innovations in metallurgy and computer modeling have allowed engineers to maximize performance without sacrificing durability.

Looking ahead, the 2026 regulations promise further evolution. The FIA plans to phase out the MGU-H while enhancing the MGU-K system, focusing on cost efficiency and sustainability. These changes will also introduce sustainable fuels, reinforcing F1's commitment to reducing its environmental footprint while preserving the sport's competitive edge.

The hybrid era has proven that turbochargers can deliver both exceptional performance and impressive efficiency when paired with advanced power management systems. This marks a stark departure from the fuel-hungry, high-boost setups of the 1980s, showcasing how evolving regulations can steer innovation in bold new directions.

Conclusion

Turbocharger development has played a pivotal role in shaping Formula One over the past fifty years, steering the sport through eras of raw horsepower, regulatory adjustments, and a growing focus on efficiency. From Renault’s groundbreaking RS01 debut in 1977 to today’s advanced hybrid power units, this technology has continually pushed the boundaries of motorsport performance.

The original turbo era showcased the sheer power and potential of forced induction, with Nelson Piquet’s 1983 championship win proving the competitive edge of turbocharged engines. This period redefined F1’s competitive dynamics, as teams harnessed unprecedented power outputs.

However, the turbo era also highlighted the risks of unchecked performance. Concerns over safety and environmental impact led to the 1989 ban, demonstrating the importance of thoughtful regulation. This shift emphasized that innovation could be guided toward achieving specific goals rather than being restricted outright.

In 2014, turbocharging returned to Formula One with a renewed purpose. The reintroduction focused on balancing performance with efficiency, incorporating hybrid systems like the MGU-K and MGU-H. These advancements transformed turbo units into energy-recovery systems, improving fuel efficiency by around 35% compared to the V8 era while still delivering close to 900 horsepower.

As the sport looks toward 2026, Formula One is set to refine its turbo technology further. The upcoming regulations will phase out the MGU-H, enhance the MGU-K, and introduce sustainable fuels, ensuring turbocharging remains integral to F1’s technical identity while aligning with modern performance and environmental priorities.

The evolution of turbocharging in Formula One reflects the broader transformation of the sport itself - from the pursuit of raw power to a focus on smarter, more efficient engineering. Manufacturers like Renault, Ferrari, BMW, and Honda have continuously driven innovation, challenging competitors to adapt and advancing the technologies that define Formula One as the pinnacle of motorsport engineering.

FAQs

How did Renault's 1977 introduction of turbochargers impact Formula One competition?

Renault shook up the Formula One world in 1977 when they introduced turbochargers, raising the bar for engine performance. These turbocharged engines delivered far more power than the naturally aspirated engines of the era, giving Renault a noticeable edge, especially on high-speed circuits. This game-changing move sparked a turbocharger arms race among teams, reshaping the competition throughout the late 1970s and into the 1980s.

By the early 1980s, turbocharged engines had become the standard for most teams, defining an entire era of Formula One. While these engines brought challenges like reliability issues and increased costs, they also pushed engineering to new limits and forever altered the sport's competitive dynamics, leaving an indelible mark on F1 history.

Why were turbochargers banned in 1989, and what effect did it have on F1 engine development?

Turbochargers were outlawed in Formula One starting in 1989 to address a trio of pressing issues: skyrocketing costs, safety concerns, and the widening performance gap between teams. By the mid-1980s, turbocharged engines were delivering jaw-dropping power - some exceeding 1,000 horsepower in qualifying setups. But this raw power came with significant trade-offs, including frequent mechanical failures, ballooning budgets, and heightened risks for drivers.

With the ban in place, the sport transitioned to naturally aspirated engines, redirecting the focus toward maximizing engine efficiency and perfecting aerodynamics. This shift sparked advancements in other areas of car design and performance, laying the groundwork for the cutting-edge technology that defines modern Formula One.

How do modern hybrid turbo systems enhance efficiency and performance compared to the turbo engines used in F1 during the 1980s?

Modern hybrid turbo systems in Formula One have transformed the game, achieving a balance between power and efficiency that the turbo engines of the 1980s could only dream of. These cutting-edge systems pair a turbocharged internal combustion engine with sophisticated energy recovery units like the MGU-H (Motor Generator Unit-Heat) and MGU-K (Motor Generator Unit-Kinetic). The result? More power, less fuel consumption.

Back in the 1980s, turbo engines were powerhouses, but they came with a hefty price: massive fuel consumption and excessive heat production. Fast forward to today, and modern hybrid systems have flipped the script. They capture energy from braking and exhaust heat, channeling it into extra power while staying within strict fuel limits. This combination gives today’s F1 cars not just incredible performance but also a level of efficiency and precision that’s light-years ahead of their predecessors.